eBook - ePub

Managing the Internationalization Process (Routledge Revivals)

The Swedish Case

Mats Forsgren

This is a test

Share book

- 114 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing the Internationalization Process (Routledge Revivals)

The Swedish Case

Mats Forsgren

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Few nations have internationalized their business operations as successfully as the Swedes. This book, first published in 1989, looks at the process in detail, examining the international operations of Swedish firms since 1970, including acquisitions of foreign firms. The international dimension of business is becoming increasingly important for firms of all sizes, and this analysis of what happens when companies enter and then sustain a presence in the international arena will be of great value to students and teachers of international business and management.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Managing the Internationalization Process (Routledge Revivals) an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Managing the Internationalization Process (Routledge Revivals) by Mats Forsgren in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Negocios y empresa & Negocios internacionales. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter one

Introduction

Electrolux is one of Sweden’s largest corporations, involved in the world-wide production and marketing of primarily household appliances. The corporation is the leading producer of vacuum cleaners on a world basis, and one of the biggest in white goods (refrigerators, freezers, dishwashers, kitchen fans, cookers, washing machines, etc.). It has an extremely international character with 63 per cent of its employment abroad, 75 per cent of sales, 57 per cent of capital investments and over 200 foreign subsidiaries in 40 countries (Larsson, 1985b).

Since 1967 Electrolux has acquired a company every six to seven weeks, mostly abroad, and has successively built up a complex structure of subsidiaries in different countries and different product lines. Some of the companies acquired are very large corporations. For instance, in 1974, the big American vacuum cleaner company National Union Electric (NUE) was acquired. Its turnover in 1979 was $270 million and the production of vacuum cleaners at the time of acquisition amounted to 2.3 million units, which can be compared to a total of 3.2 million units in the other Electrolux companies, of which 0.4 million were in Sweden. This acquisition meant that at one fell swoop about 40 per cent of the group’s total vacuum cleaner manufacture was concentrated to a single subsidiary. This was then the biggest deal ever in the history of Electrolux, and one of the largest to be transacted by a Swedish company abroad.

This has been followed by other major acquisitions, mainly in the white goods sector. In 1976, for instance, Electrolux acquired one of the leading producers and distributors of household appliances in France, Arthur Martin, with a turnover at the time of approximately 800 million francs, or more than 12 per cent of Electrolux’s total turnover and 25 per cent of the turnover from its Swedish production. This meant that about 50 per cent of Electrolux’s stove manufacture was then based in France.

Comments by Electrolux management on the cause and effects of the NUE acquisition suggest that they ‘preferred a less dominant Swedish share in a strong group to a predominant Swedish share in a weak group’ (SOU, 1981: 43). This remark reflects in a nutshell the latest phase in the internationalization of Swedish industry. Most of the companies which have dominated this development in recent years are large, they have a long international history, and they display a high degree of internationalization. In the past the internationalization of industry has often been described as a gradually increasing commitment to markets further and further away, but always with a strong and dominant base in Sweden. Although the overseas operations in the shape of sales companies and/or manufacturing companies have gradually grown stronger in their respective markets, the function of the foreign subsidiaries has still been to act as the long arm of the parent company and to disseminate its products and its know-how throughout the world. The internationalization of these companies has generally been described in terms of geographically controlled growth spreading wider and wider like rings on the water, but there has never been any doubt about which is the centre and which the periphery.

In the light of developments in recent years this picture calls for adjustment on at least two counts. First, the foreign-based operations of many companies have become so extensive and so dominant that the idea of centre and periphery must be modified. In many cases the overseas subsidiaries have become larger in terms of operations than comparable members of the group in Sweden, and have acquired a greater range of production and product programmes as well as their own product development. The overseas subsidiaries on the largest markets are often combined in a holding company; a kind of group within the group.

Case studies of foreign investments made by Swedish firms during the last 10–15 years indicate that these investments are in large measure initiated by foreign subsidiaries, and related to activities in these companies rather than to the parent company. Instead of the old picture of the parent firm making market-orientated foreign investments strongly related to its own operations in Sweden, we have gradually acquired a new picture in which the old periphery becomes a centre for new investments motivated by economic forces in the industrial structure in the country or the area to which the foreign subsidaries belong. The higher the firm’s degree of internationalization the greater the probability that the foreign investments will be of a ‘foreign-based’ character, that is motivated, initiated and implemented by the foreign subsidiaries. In a study of strategic decisions in Electrolux, a member of the group executive committee is quoted as follows:

Impulses to acquire can come from various directions, from subsidiary presidents, from chief executives of product lines, directly from here […]. You must remember that you are strategically circumscribed by your present structure. (Jallinder, 1982, author’s translation)

Second, the approach to internationalization has changed. The usual method of establishment in a market through an agent, followed first by a wholly-owned sales company and later by wholly-controlled production units, has been increasingly replaced by the acquisition of foreign companies. These acquisitions frequently involve major instantaneous steps in the internationalization and incorporation into the group of large independent companies. The increasing importance of foreign acquisitions may also in itself reflect a growing influence on the part of the overseas operations on group investments.

This last trend can be illustrated by the PLM case. PLM is a Swedish corporation primarily involved in the packaging industry. As the Swedish market for glass packaging stagnated during the 1960s, the company actively engaged in a search for a manufacturing platform in Europe for the European market. The mission given to the manager of the export division in 1966 was:

Dispose of available surplus capacity in markets outside the Nordic countries. In this way we will get to know the European markets for glass packages. This knowledge will be useful for the creation of our own glass mills within the EC. Don’t buy existing units, build new ones! (SOU, 1981: 43, author’s translation)

The last part of the plan came to nothing. Partly because PLM overestimated its comparative advantage in the production and marketing of glasses and partly as a result of the declining market for non-returnable bottles, it had to abandon its ambition to make de novo investments. After a while the search was directed instead at finding a suitable glass package company for acquisition in West Germany, which has one of the biggest markets in Europe for beverage glass packagings. But there were no companies for sale in West Germany, and time passed. When, in 1969, PLM suddently received an offer to buy a glass mill in the Netherlands they decided to take it up, even though this was a much smaller market than West Germany. The search for a German company continued none the less, and in 1971, five years after the initiation of the plan to invest abroad, an opportunity arose to buy a rather small and run-down mill in Münder in West Germany.

The way these foreign investments were made and the type of products which are actually manufactured in the subsidiaries differed very much from the original plans of 1966. None the less the firms acquired soon achieved a dominating position in PLM’s glass packaging production. In 1972 they accounted for 40 per cent of total production, and by 1978 for 60 per cent. Immediately after the acquisitions in the Netherlands and West Germany, PLM’s glass manufacture was divided between a domestic section and an international section in which all European activities, production as well as marketing, were managed from the Dutch subsidiary. This second section was made a division on its own, to be known as Euroglass (SOU, 1981: 43).

This formal separation was further reinforced because of the more intensive product and process development in the Euroglass division, compared to the Swedish glass division. This was a result of the stagnation of the Swedish market, combined with a higher degree of competition among the European producers. What began as the result of a perceived firm-specific advantage in the 1960s, proved to be a genuine dependency upon the industrial structure and other location-specific factors in the foreign markets. This in turn caused a gradual transfer of glass packaging competence in technological terms from the Swedish units to the subsidiaries operating to a greater extent in the foreign market. As it turned out, the Euroglass division became increasingly independent of resources from the parent company, and its relative profitability strengthened its position in the group to such a degree that the Swedish glass division might seem to have been more dependent on the foreign subsidiaries than vice versa (SOU, 1981: 43; Larsson 1985b).

Traditional foreign direct investment theory is not altogether suited to analysing this new pattern of internationalization. First of all the theory does not distinguish between ‘beginners’ and those companies which are far advanced in the internationalization process. The forces that motivate and implement foreign investment in these two situations can be quite different. For a ‘beginner’ a firm-specific advantage related to assets in the home country can be of crucial importance when establishing subsidiaries in a foreign market. For an internationally experienced firm which already has large assets abroad, the driving force behind reinvestments aimed at keeping the foreign operation in good shape, as well as behind new investment (de novo or acquisitions) may well be the foreign assets themselves rather than the home base. If an inter-organizational perspective is adopted, whereby foreign investment can be seen as a way of managing strategic interdependencies within the industrial network to which the investor belongs, then existing foreign subsidiaries and their networks abroad will occupy an increasingly important position in an analysis of these investments.

Second, traditional theory has devoted little attention to acquisitions as a method of internationalization. The assumption of a firm-specific advantage, which is such an important concept in the explanation of foreign direct investment in the theory, is difficult to relate to investment through acquisition, at least if we assume that control over this advantage, primarily knowledge of some kind, is hardest to maintain in the case of acquisition. Acquisition can be a quick route to internationalization when the firm-specific advantage is not strong enough, as the PLM case indicates, or it may be a question of handling the strategic interdependencies of foreign subsidiaries (some people would call it restructuring the industry), as the Electrolux case indicates.

Implicit in foreign direct investment theory and explicit in the traditional management theory of international business is also the assumption that the parent company or group executive decides and carries out the overseas investments. In other words, there is a clear hierarchic perspective in most writing on foreign direct investments and on the organizations which make these investments. But if we accept that ‘the centre-periphery perspective’ on international business is gradually being superseded or at least supplemented by a ‘centre–centre’ perspective, we must also pay more attention to the way in which the investment policy in the groups is determined. A centre–centre perspective means that we tend to look upon the investing organization as a coalition of interests in the tradition of Cyert–March and Pfeffer, rather than as rational decision-making mechanisms (Cyert and March, 1963; Pfeffer, 1978a, Pfeffer 1978b, Pfeffer and Salancik 1978). An international firm with subsidiaries in different countries, some very large even compared to the Swedish units, and working in different product areas, constitutes a system embracing a number of interests, sometimes with strong interdependencies and sometimes rather loosely linked. In this perspective it is recognized not only that the national interests and the local industrial networks which surround the overseas units are important factors when it comes to investment policy, but also that other units apart from headquarters, and including the foreign subsidiaries, can have a profound influence on this policy through their control of critical resources.

This perspective also affects our view of foreign investment as a decision process. Implicit in the hierarchic perspective is the idea that a foreign investment is an act of rational decision making according to a plan. This perspective has been called in question in organization theory and in various writings on strategy formation (see Weick 1969; Mintzberg, 1988), but has nevertheless continued to influence writings on foreign investment behaviour up to the present. But as the PLM case indicates, the actual foreign investment can be described at least partly as ‘emerging’ rather than as ‘intended’. Foreign investment behaviour should perhaps be described instead as a pattern in a stream of activities which becomes apparent after a while and which is then described by top management as the corporate strategy.

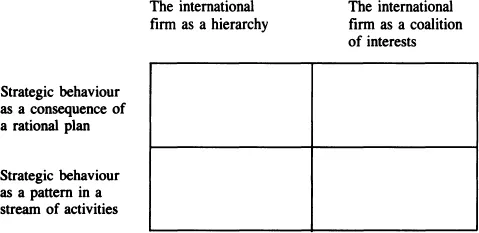

The dichotomy of the hierarchical/political view and the strategic decision as plan or pattern gives us a matrix of four perspectives on the internationalization process, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Fig. 1.1 Four perspectives on the internationalization process

The upper left quadrant contains the traditional view of foreign investment, which means that large part of the literature on the subject belongs to this area. Typical questions in this tradition are for example: Why does foreign direct investment occur in the first place? and which industries or firms are most active as foreign investors? The foreign direct investment theory that is based on industrial organization theory or internalization theory, as well as most writings on global strategies, belong to this area (see Vernon, 1966; Kindleberger, 1969; Caves, 1971, 1982; Buckley and Casson, 1976; Hymer, 1976; Dunning, 1980; Hennart, 1982; Rugman, 1982; Doz, 1986; and Porter, 1986). The assumption that the foreign investment decision is the result of a rational plan, and that it is decided and implemented by top management, is at least implicit in these studies. Related to this tradition are also several studies about the organization of foreign operations, especially the degree of autonomy that the head office should allow to foreign subsidiaries (see for example, Goehle, 1980; Hedlund, 1981). Given the environment, the technology, the size and other characteristics of the subsidiary, these studies analyse the design of the international firm’s organization as a top management decision problem. A contingency approach is adopted.

Studies in the lower left quadrant are not as frequent as in the first quadrant. The typical questions according to this tradition are not so much why foreign direct investment occurs and how the foreign operations should be organized, as how the internationalization process appears at the level of the firm, and how it can be interpreted in retrospect. Implicit in these studies is the view of foreign investment as an incremental process, in which commitments to certain projects and successive experiential knowledge about foreign markets ultimately endow the internationalization with rather a different character from that of the ‘rational plan’. A work often cited in this tradition is Aharoni’s investigation of American firms investing in Israel (Aharoni, 1966). The so-called Uppsala School, which describes the internationalization of firms as a process whereby firms gradually increase their international involvement, by using first agents followed by sales subsidiaries and ultimately by using production units, beginning with countries at the shortest mental distance from the home country, also belongs to this tradition (Kinch, 1974; Forsgren and Johanson, 1975; Johanson and Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975; Johanson et al., 1976; and Johanson and Vahlne, 1977). Like traditional foreign direct investment theory, the Uppsala School posits a firm-specific advantage as a prerequisite for internationalization. But unlike the earlier tradition, the Uppsala School argues that the original firm-specific advantage, perhaps in the form of technical knowledge, does not explain the further internationalization process. Instead it stresses the importance of specific knowledge about national markets and customers that can only be gained from personal experience that is inseparable from the individuals who possess the knowledge and cannot be transmitted to other markets. This explains the incremental character of the internationalization process.

Inherent in this tradition is the argument that decisions may emerge as a consequence of action rather than guiding action a priori, a sort of retrospective rationality (Pfeffer, 1981). Preferences may be discovered and uncovered through actions, and it is this which give the internationalization process its ‘unplanned’ character.

Studies of the international firm in a more political perspective, which see the organization as a coalition of interests rather than as a hierarchical system, are not very common. A lot of works have been concerned with the centralization/decentralization issue in the international firm, but these studies adopt a fairly pronounced headquarters perspective, focusing more on the formal aspects of power and the granting of autonomy to the foreign subsidiaries (see Brooke and Remmers, 1977; Hulbert and Brandt, 1980; and van den Bulcke and Halsberghe, 1984).

Two studies which have adopted a more pronounced political approach to international firms should be mentioned. The first is Jannis Kallinikos’ study of some Swedish-owned subsidiaries in Greece and of their influence on divisional and corporate strategic decisions (Kallinikos, 1984). The second is Anders Collman’s study of the relation between power and structural changes in multinational enterprises (Larsson, 1985a). In both studies it is assumed that the power which the foreign subsidiaries exercise over the foreign investment decision and the organization of the international firm are based on the control of critical resources rather than on formal authority. The subsidiaries’ power is acquired by way of this control; it is not given to them by a group management’s decision on the centralization/decentralization issue. In the terminology of the Uppsala School, we could say that the political perspective stresses the fact that a great deal o...