![]()

1 No future?

Mass unemployment re-emerged in developed countries in the 1970s. On some estimates, it has already lasted longer than the similar experience of the 1930s. Over a hundred million years of potential labour supply has been unused in the OECD area alone. Thirty million people are officially classified as out of work, one tenth of them in Britain, where long-term unemployment is still static despite special measures to alleviate it. Nearly a million and a half people have not found work after more than a year's search.

In Britain, a climate of acquiescence in mass unemployment is already developing. Some have begun to question the basis of unemployment figures, suggesting that a true count would be lower. Many commentators now argue that we must learn to live with a different notion of work to that of permanent employment for all. Certainly most of the long-term economic forecasts of the UK economy expect no significant fall in unemployment on present policies by the end of the decade. This has even been accepted by government departments as a working assumption (Department of Trade and Industry, 1986). And the general pessimism seems to be shared by the unemployed; one in five of these, questioned in late 1985, expected that they would never work again.1

What has caused mass unemployment? This book attributes it to a weakening in economic growth generally, for reasons explained later. It is not the case that the huge increase in job losses and job seekers has been caused by an increased labour force.2 Nor is it true that there is now a greater proclivity for leisure and that much unemployment is 'voluntary'.3 It may of course be that there is less of a stigma attached to unemployment when jobs are difficult to find and this may have had some effect on people's willingness to work, especially in the case of young people or those on low pay.4 Mass unemployment will also have caused depression and lethargy, with a resultant effect on capacity to work. However, these phenomena are consequences not causes. The main reason for high unemployment must be found in the weak growth of output and in the reduced labour requirement to produce that output.

It is possible to distinguish three broadly differing positions in policy-making circles accounting for the emergence and persistence of unemployment and slow growth.

The first view, which is sometimes termed 'classical', sees the problem as arising in the labour market, with real wages too high and profitability correspondingly low. This results in less expansionary investment and a greater reliance on laboursaving techniques.5 Inflationary pressures also work to keep unemployment high. The route to this can be direct, as when prices rise and demand falls, or indirect, due to contradictionary measures to contain inflation. Attempts to generate fuller employment by stimulating demand will, on this view, be self-defeating. Unemployment will persist until the real wage moderates or until technical change or a reduction in costs improves profitability and induces expansion.

The second view, which will be termed Keynesian, is dominated by a consideration of the role of autonomous demand on output growth. It is recognised that some elements of autonomous demand - say an increase in North-South trade - are not susceptible to policies of individual states. A number of Keynesians will even admit to a belief that the longrun level of demand is completely endogenous. However there is a unified belief that short-run policy measures can at least prevent an economy sticking in an under-employment state below that long-run level of demand. The main constraint on policy is inflation; it is widely accepted that this is in large part attributable to real-wage pressure, which is seen as having intensified considerably during the 1970s. Keynesians prefer to concentrate not on the source but on the transmission of that pressure via money, wages and prices. The real constraint on policy is thus the ability of institutional methods to resolve social conflict over distribution, especially in the presence of external shocks which disturb accustomed claims on output:

the characteristics of pay setting, together with the institutional arrangements and methods associated with collective bargaining, coupled with shocks to the economic system and policies designed to bring inflation under control tend to generate high and persistent levels of unemployment. (Morris and Sinclair, 1985, p. 11)

The two views just outlined do not necessarily conflict, and Layard and Nickell (1985a) have called the debate fruitless since it is quite possible for real-wage pressure to be a serious problem without actual real wages being too high. This is explainable by the role of government deflationary measures in containing price rises. It is then very difficult to know whether demand or wages should be identified as the culprit. It is important to note, however, that the Layard and Nickell synthesis of classical and Keynesian views singles out the labour market - and its failure to operate without building up real-wage pressure - as the villain of the piece.6

The structural view

This is where the third view (advanced in this book) parts company with the traditional approach just outlined. This third view, which will be termed 'structural', differs from the others in that it does not locate the origin of the unemployment in the labour market. The problems of an imperfect labour market are not new and it is difficult to understand why they should now wreak such havoc on employment opportunities. Economists such as Bruno and Sachs (1985) have gone to great lengths to document possible factors behind the increase in real-wage pressure in the 1970s, instancing such factors as incomes policies in the 1960s, the 'May events' (France, 1968) and the 'hot Autumn' (Italy, 1969), but the discussion seems more descriptive than analytical.

It is difficult to see labour-market problems as a causa causans in the sense of being independent of other pressures. For instance, it is known that labour mobility between jobs lessened dramatically at the end of the 1970s; however, this was not caused by a sudden malfunctioning of the labour market but by the fear of unemployment, consequent on slow growth.7

The structural view argues that economic development is punctuated by periods of unusual structural change to which market economies find it difficult to adapt because of heightened uncertainty over the direction of change. Such periods are characterised by unbalanced preoccupation with cost-cutting rather than exploiting new opportunities for expansion inherent in new technologies and ways of working. There are thus three propositions which need to be argued in defence of the relevance to current economic conditions of the structural view. Firstly, that structural change is unusually high; secondly, that cost-cutting has become a priority for firms; and thirdly, that uncertainty over the future evolution of economic variables has risen. Each of these points is supported below.

Structural change

The notion that structural change is at an unusually high level may strike some observers as obvious, especially in the case of Britain in the last few years. Nevertheless, it is important to establish this point as it has become a controversial one among economists.8 Some economists, especially those with an interest in technology, do argue that unemployment has a significant structural element, in the sense of increased mismatch in skills, regional location and types of capital goods, as a result of greater technical change (Soete and Freeman, 1982). But this is not generally accepted by others. For instance, Nickell (1985) has argued that 'the current period has a level of structural change which is quite unremarkable' (p. 108). Nickell's view is based on a very long view of the data, which may not be appropriate given changes in industrial classification, but even on his own figures, structural change has risen perceptibly since the late 1960s. Furthermore there is more than one method of measuring structural change, and

Panel 1.1

Structural Change

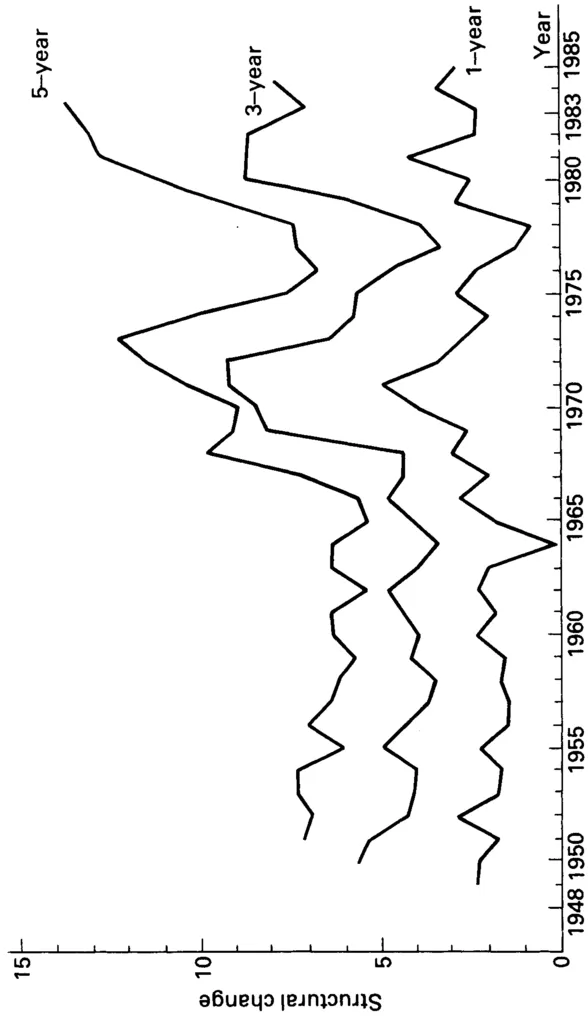

indices of structural change in the whole economy since 1948 are considered here. The index is constructed by summing across twenty-three sectors the absolute value of the change in employment proportions that occurs over each time period. Nickell's view is based on differences over one year, as calculated by Newell (1984). However, this will include a lot of noise due to purely cyclical variation and it seems more appropriate to use longer periods for differencing. Figure 1.1 shows how the index of structural change has increased in recent years, especially when longer differencing periods are taken. The dip in the early 1970s confirms the results of Layard, Nickell and Jackman (1984), who observed such a fall in a number of OECD countries using cyclically averaged data. It would appear that the accommodatory policies used in the wake of the first OPEC price rise, and the subsequent moderate expansion in the OECD area, may have dampened structural change, with companies preferring a cautious approach.

reliable indicators suggest a much increased level for the 1980s. Panel 1.1 details the evidence.

It is important to note that the high level of structural change does not connote a successful transition to a new industrial structure. The index of change counts negative and positive movements (i.e. losses and gains in capacity) equally and a sharp loss of capacity in some industries, unbalanced by any major gains, will also show up as unusual structural change. Nevertheless, it does appear that change has accelerated and this has implications for economic policy that will be brought out later in the book, in particular the necessity for increased attention to education and training and the justification that it offers for higher public borrowing.

Cost-cutting

Fixed investment in many countries has become biased towards cost-saving rather than new expansion. Some see this as resulting from wage push, but it is more likely that the most powerful stimulus to this type of investment is increased uncertainty in product markets, as discussed later.

OECD sources pointed to this emphasis on cost-cutting even before the second oil-price hike in the late 1970s. The McCracken report (1977) commented on 'a fall in the share of investment going to extensions of capacity' and went on to cite business survey data in support of this claim. In Germany, for example, the proportion of manufacturing companies giving expansion of capacity as the principal reason for investment fell from over half in 1960 to only 15 per cent in the late 1970s, and, although it then rose, it was still only 30 per cent by early 1986.

In the United States, OECD statistics based on the McGraw-Hill survey of business plans suggest that, in the wake of the second oil shock, the 1980 figure for the proportion of modernisation in total investment was the highest since 1961. A similar story can be read from the figure on the proportion of capital stock accounted for by modernisation investment; this was at an all-time high in 1980, following a climb from a twenty-year stable average up to the mid-1970s.9

Evidence for the UK is more indirect, but still striking. Since the last quarter of 1979, the CBI Industrial Trends Survey has recorded whether investment is for capacity expansion or for increased efficiency. This data reveals a sharp rise in the proportion of efficiency investment after 1979, and it would be of interest to observe earlier figures. While these cannot be obtained directly, it has proved possible to infer the general historical pattern, which again confirms a swing away from expansionary investment. This is detailed in Panel 1.2.

For all these countries it appears then that there is evidence of a bias towards cost-saving investment within manufacturing. One major consequence of this has been an increasingly

Figure 1.1 Indices of structural change: one-, three- and five-year differences

Panel 1.2

A simple model was constructed by regressing the ratio of the expansion-to-efficiency investment series on what might be regarded as a good proxy-the ratio of investment in new building and works to investment in plant and machinery. The results were then used to construct annual historical figures for the ratio of capacity building investment to efficiency investment. The constructed series (ACE) was then regressed on time and on the square of time to determine its historical evolution. The best equation was obtained when the squared term was entered with the constant, giving:

ACE = 0.56 - 0.00085T2 (16.25) (-6.00)

Where T represents Time. The figures in brackets are 't' statistics.

R2 = 0.61; DW = 1.51; annual constructed data 1962-83

This suggests an acceleration overtime in the proportion of efficiency investment.

sluggish response of employment to output growth in recent decades.

Several studies have confirmed this shift, both for Britain and for the OECD generally.10 The testing has usually been confined to manufacturing, in view of the unreliability of the data on service-sector output and employment; some results for UK non-manufacturing will be discussed later.

An important finding of the studies has been that the generation of net new jobs now requires a higher output growth than was needed in earlier decades (Cornwall, 1977; Michl, 1985). Cornwall has calculated that for the manufacturing sectors of OECD countries in the 1950s, an output growth in manufacturing of a mere 1.7 per cent would have resulted in employment growth. By t...