1.1 History of containerization

After the end of World War II, economic gaps among countries were wider than they had been before, and there were huge demands on all kinds of resources. This led to the blossoming of international trade and transportation. At that time, most of the manufacturing industries were located in Europe and the United States, and this was one of the main reasons for the large proportion of transportation in these two regions.

Later on, with the surge in demands, manufacturers had to import raw materials such as crude oil, metal ore, rubber and timber from other countries in the Middle East, South America, India and Australia. Marine transportation in these areas started blooming in the 1950s, and double-digit growth per year was not uncommon in those countries in the next thirty to forty years. However, there was an insufficient supply in marine transportation in terms of vessels and ports, and ship chartering became one of the hottest businesses in Wall Street.

Basically, cargoes in marine transport include crude oil, metal ore, timber (logs), rubber, grains, semi-finished goods (steel, cement, timber plank, pulp products, etc.) and finished goods (consumables, electrical appliances, vehicles, food, etc.). In general, they can be classified into two major categories, bulk cargo and break-bulk cargo (also called “general cargo”). Apart from the form of the cargo, the main difference between these two categories of cargo is their price. For example, the price of coal is in general less than US$100 per ton, but the price of electronic products could be more than US$1,000 each. The sensitivity of transportation cost in comparison to the cost of the cargo does vary significantly. Based on this price difference, the development trend of bulk carriers is to increase their size, while general cargo vessels aim for having higher speed.

In the early days of marine transportation, a general cargo vessel would house different kinds of cargo in its different compartments. With the increase in cargo volumes owing to the increase in international business, the vessel operators were able to develop dedicated vessels designed for a particular type of cargo so as to increase the economic benefits. These included oil tanker, ore carrier, bulk carrier, log carrier and so forth. On the other hand, the size of the vessels increased from several thousand to several hundred thousand tons.

Even though large-scale, purpose-built vessels became more common in those days, finished products that were usually classified as break-bulk cargoes still could not be transported in vast amounts, mainly because the carton box (packing of finished cargo) is not strong enough for stacking high, and wooden and/or metal boxes could not be placed on top. This left a lot of space inside the vessel compartment unused (broken space), and the cost of transportation remained high. In general, only two thirds of the vessel’s capacity could be utilized for this type of cargo. In the 1970s, the largest vessel for break-bulk cargo was still around 40,000 displacement tonnage only.

Another major issue faced by the transportation of finished products was burglary. Finished products were usually smaller and lighter but high in price. This made items such as electrical appliances, daily consumables, precious goods and so forth the major targets for burglary during transportation starting from the very beginning. During the early 1960s, plenty of electrical appliances exported from Japan and almost none of the vessels departing from Japan could avoid burglary. Apart from being stolen at the port, these finished products might also be stolen during the voyage. Burglary, as a result, was excluded from marine insurance during a certain period of time.

Starting from early 1960s, some general cargo vessels had started the use of “metal box”. Precious products were placed inside these (relatively) large-volume metal boxes, which were locked until they were delivered to the destination port and the boxes were opened by the consignee. This greatly reduced the chance of burglary. However, the weight of the loaded metal boxes usually exceeded five tons. This created another challenge to the general cargo vessels, as their derricks did not have as much lifting capacity in those days. In the late 1960s, some vessels and ports modified their equipment such that the lifting capacity increased to 15 tons, and the container industry started to bloom from that period.

1.2 Containers

The use of containers as the transportation means for commercial use does not have a long history, even though the use of boxes similar to modern containers had been used for combined rail- and horse-drawn transport in England as early as 1792 (World Shipping Council, www.worldshipping.org/about-the-industry/history-of-containerization).

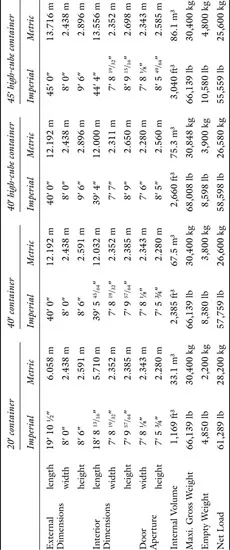

The evolution of modern standard-sized containers started with the U.S. government during World War II, which required a speedy and efficient means for transporting military resources. Originally containers were designed as 8-feet (2.44 m) wide and 8-feet (2.44 m) high. Taller containers have been introduced to the market, including 9 feet 6 inches (2.9 m) and others, which are all classified as “high-cube” in the industry. The lengths of the containers are nominally 20 feet (6.1 m) and 40 feet (12.19 m), and this is how the standard unit of the industry – twenty-feet equivalent unit (TEU) – was derived. Lifting holes, also known as corner casting, are installed at all corners of a container, and these are the lifting points for container-handling equipment, as well

Table 1.1 Dimensions and weights of standard containers

as the locations for installing twist locks between containers when they are stacked.

In January 1968, the World International Organization for Standardization (ISO) issued the first notice to define a shipping container, including the terminology, dimensions and ratings. In July 1968, ISO issued the second notice regarding the identification markings of a shipping container. In January 1970, ISO suggested standardizing all corner castings on the top and bottom of the container. In October of the same year, the interior dimensions (cargo space) of “general-purpose containers” (GP boxes) was regulated and defined.

Containers at 45 feet, 48 feet and 53 feet are not uncommon in the industry nowadays, especially for lightweight, bulky cargoes. Their lifting holes are not only at the corners of the containers but also at the 40-foot position. This is because most of the container-handling equipment can only handle containers with lifting holes at either 20-foot or 40-foot positions.

In order to store different types of cargoes safely and cost effectively, various types of containers are now available in the market, including:

- Collapsible

- Gas bottle

- Generator

- General-purpose dry van for boxes, high or half height

- High-cube pallet-wide containers

- Reefer containers

- Open-top bulktainers for bulk minerals or heavy machinery

- Open side for loading oversize pallets

- Platform

- Rolling floor for difficult-to-handle cargo

- Tank container for bulk liquids and dangerous goods

- Ventilated containers for organic products requiring ventilation

- Garmentainers for shipping garments on hangers

- Flush-folding flat-rack containers

1.3 Container vessels

The first container vessel was not purposely built but was converted from oil tankers T2 (oil tankers constructed and produced in large quantities in the United States during World War II) back in the 1940s after World War II. In 1951, the first purpose-built container vessel began operating in Denmark, whilst the first container vessel successfully used commercially was the Ideal X (Levinson, 2006 p. 1). The main feature of a container vessel is the vertical guide rails for aligning the containers within its hull. With the use of robust hatch covers, containers are also stacked above the hatch. At present, the largest container vessel in commercial operation has the capacity of 18,000 TEU.

As mentioned in the previous section, a container usually weighs 10 tons or more when it is fully loaded. When the first laden containers were loaded onto a general cargo vessel, that created a big problem – the vessel that was originally designed for uniformly distributed loads (break-bulk cargo) could not withstand the concentrated load at the four corners of the containers. The simplest way to resolve this problem was to locally strengthen the floor of the compartment.

However, there emerged another problem. Containers stored inside a vessel could not be held in position because of rocking and vibration during voyage, and this problem could not be resolved by simply tying the containers by wires. Finally,...