![]()

Part I

City vs countryside

![]()

1 Migration, prejudice and early industrialisation in the emergence of a modern metropolis

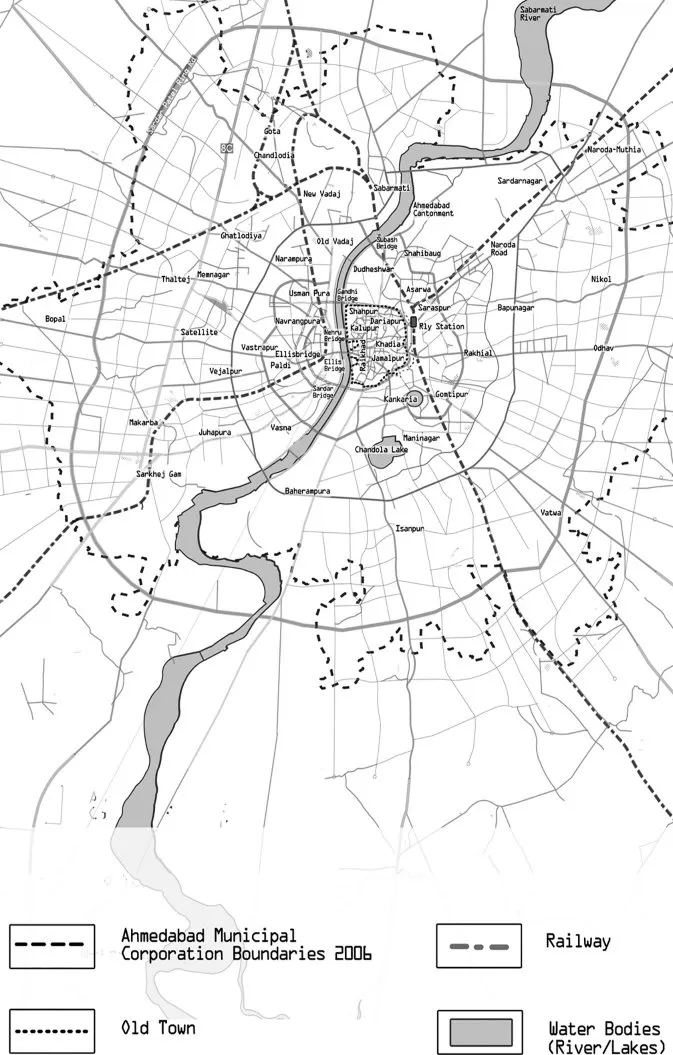

Figure 1.1 Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation

From city to metropolitan area

Understanding the way in which a medium-size Indian town became a prospective metropolis by the end of the nineteenth century, requires an effort of imagination. The dynamics that contributed to direct Ahmedabad on the way to expansion and ‘modernisation’ are many and interacted at various levels, changing the city’s economy, the network of relationships and balances amongst its socio-religious groups, the culture, the space and territory. A major part of the metropolis of today consisted of open fields a century ago, and the most significant implications of the territorial expansion of the city are to be sought in the interrelation of the transformation of space and the population increase, which brought millions of individuals of different origins, religions, and cultural traditions to settle in the city, or near it, sharing a relatively limited space where coexistence had to be constantly negotiated.

The boundary separating the urban and the rural appears as a less clear-cut demarcation, in the same way as certain categories that one uses to define the urban territory, such as periphery, or slum, acquire a deeper significance if seen in the context of long-term processes of spatial and social transformation. The network of relationships between city and countryside, and between urban and rural people, must be considered as part of the dynamic of urban transformation, something that actively participates in the shaping of a metropolis.1

When British writer James Forbes arrived in Ahmedabad in 1781, the overall landscape encompassing the city and its surrounding areas was of course very different from today.2 For him, observing the landscape and visiting the nearby villages and suburbs became a first step in acquiring important information about the city’s past and, as a consequence, about its condition at the time:

The nearer we approached the capital the more we traced the former splendour and magnificence of the moguls: ruined palaces, gardens, and mausoleums, which once adorned the country, now add a striking and melancholy feature to its desolation; these are conspicuous in every village in the campagna of Ahmedabad, and form a striking contrast to the mud cottages and thatched hovels of the Mahratta peasantry.3

The beauty and regality of the Mughal capital appeared in striking contrast with the abandonment of the city at that time, and that contrast was even more evident on a larger scale. During its most flourishing periods (throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries), the countryside around Ahmedabad was integrally connected to the city. The link was not only a one-way flow of people and primary products from the country to the city, nor was it based on land ownership patterns that would guarantee the flow of capital from the exploitation of the agrarian labourers.4 The countryside around Ahmedabad was spotted with rural villages of various dimensions, and with places intimately related to the city proper, such as the pura (small settlements immersed in gardens, founded to host Mughal officers and their entourages), as well as Muslim cemeteries (which were never allowed within the city),5 shrines, temples, gardens, factories and water reservoirs.6 By the late eighteenth century, most of these places were abandoned or in ruins, fields were less cultivated than in many other districts of Gujarat, the land being ‘much infested’ by groups of bandits.7 The decay of the Mughal empire, and decades of instability and conflict under the dominance of the Maratha had brought insecurity to the whole region, contributing to a progressive decrease in trade to and from the city and, more generally, to a gradual depopulation of the areas around the city.8

The consequences of decades of political instability were not only visible in terms of decaying palaces and a reduction in the economic activities of the city’s merchants. With respect to the time when it had been the capital of the western province of the Mughal empire, at the beginning of the nineteenth century Ahmedabad was no longer a pole of attraction for short- and long-distance exchanges of people and capital. Urban elites were still active and engaged in trade, but the city was more isolated from the rest of the region.9 The description of a desolate countryside, with dacoits (bandits) storming the villages and the old vestiges of the past in ruin, suggests how the decadence of the city corresponded to an impoverishment of the entire system linking Ahmedabad and its surroundings.

This background is essential to an understanding of the subsequent phases of growth and economic renaissance of Ahmedabad city. After taking over the city in 1817, the British paid great attention to reconstructing and renovating the urban space, as well as the city’s economy. Money collected from town dues was used to repair the city walls, widen the streets and fund other municipal works.10 This investment in urban planning was meant to facilitate the control and administration of the city and at the same time was successful in restoring a favourable environment for merchants and entrepreneurs in order to revive the city’s economic activities. From this perspective, the British administration played a key role in the central decades of the nineteenth century in boosting both the city’s space and its economy by granting more security and a more attentive management of the urban resources. Following a general improvement in the overall environment, Ahmedabad entered a new phase of growth. The population, which had decreased drastically towards the end of the eighteenth century, began to increase again. From about 70,000 in the 1810s, it reached 90,000 during the 1840s and crossed the threshold of 100,000 units at the beginning of the 1880s.11

Still, the district remained essentially rural in terms of demographic distribution and settlements, since about 71 per cent of the population lived in small villages (i.e. of less than 2,000 inhabitants).12 Considering the city as embedded in a system of relationships on a wider geographical scale provides a more comprehensive perspective for investigating the long-term dynamics that transformed the city over time. In Raymond Williams’ words, ‘What was happening in the “city”, the “metropolitan” economy, determined and was determined by what was made to happen in the “country”; first the local hinterland and then the vast regions beyond it’.13 In the process that led Ahmedabad to become a large metropolis, the rural–urban dichotomy represented a constant factor and, more importantly, it did not affect only the economic sphere, as Williams suggests in his work, but informed the way in which the living space was organised and the choices that people made as to where and how to live in the city, and emerged constantly as an underlying discourse in the dialectic between the public authority and the city’s inhabitants.

Towards industrialisation: from the ruins of the old capital to the chimneys of the textile industries

Let us rely again on James Forbes’ eyes in approaching Ahmedabad. His arrival in the old capital provides a vivid portrait of the decay into which the city had fallen:

From Petwah we travelled over a tract of land, once filled with crowded streets and populous mansions, now a cultivated plain, covered with trees and verdure, unless where a falling mosque or mouldering palace reminded us of its former state. These ruins increased as we drew nearer the city, until at length we travelled through acres of desolation. An universal silence reigned; nothing indicated our approach to a capital.14

The view from within the gates was no more comforting; the wrecked walls provided a habitat for ‘tigers, hyenas, and jackals’, while many families ‘lived in the gloom of obscurity and felt the degradation of poverty’.15 This was the impression the city, once ‘as large as London’, conveyed to the eyes of an English traveller and keen observer such as Forbes.16 In the desolation of those decades, many areas within the walls had been converted to farming and animal husbandry, whilst the ancient gardens and fountains were neglected. Such a situation persisted even during the first decades of British rule, as vacant lands persisted for many years despite a partial recolonisation of the city.

After six decades of British administration Ahmedabad had partially lost its aura of an ancient capital in decay. Old Mughal palaces and places of worship were still abandoned, but new buildings and infrastructure were being built, reshaping the internal structure of the walled city and enhancing its links with the network of villages and settlements surrounding it. The 1879 Gazetteer provides a very detailed description of the condition of the various areas in and around Ahmedabad, which is very useful in understanding how the city, and its population, were ‘moving’ at the dawn of its industrialisation. From 1830, the Town Wall Fund, which was then converted into the Municipal Commission in 1856, had planned and realised several works in order to deal with the most urgent structural problems of the city, such as overcrowding, bad sanitation, and lack of clean water. Efforts on the part of the administrators did not always produce satisfactory results, but overall living conditions in the city improved.17 Hence, on the one hand the middle decades of the nineteenth century witnessed an effort to modernise the city through the conception and imposition of a model of urban planning. On the other, during these first phases of urban expansion, unregulated settlements continued to overlap with planned developments; formal and informal dwellings mingled, representing constant challenges to the projects of the regulators.

In describing the reorganisation of Ahmedabad during those years, Kenneth Gillion interprets the dynamics which led to the formation of a city government, in terms of a dialectic between the colonial rulers and the local elites.18 He stresses the fact that local groups actively participated in the modernisation of the city, by being involved in the urban administration and by driving the city’s economy through a phase of constant recovery that culminated towards the end of the century in the booming of the textile industry.19 In this sense, while he regards the level of participation of local elites in the management of the city as something uncommon to most other Indian cities, he also notes that the experience of self-government was marked by a troublesome confrontation with the colonial authority, which culminated with the Municipal Corporation being suspended by the British for incompetence in 1910.20 As part of this confrontation, local groups often challenged the decisions taken by the colonial administrators, using at times culturally-based arguments and at times economic considerations. Thus the urban territory became the stage for a struggle for power and authority, where ‘foreign rulers had to contend with differences in values and customs’ on the part of the local elites, and the result was often that projects of development and improvement remained on paper.21

Gillion identifies the period during which the local administration progressively failed to keep the urban territory under control with the first phase of expansion of the textile industry in the city, beginning in the late 1860s. The rapid flourishing of industries in the city contributed to further exposing structural problems related to sanitation, overcrowding and housing. In 1888 it was said of the area of Saraspur, on the eastern outskirts of the walled city, that its condition ‘would disgrace the most uncivilised hamlet in India’.22 However, although Gillion stresses the relationship between industrial expansion and urban problems, he places it in the context of the dynamic of confrontation between British administrators and traditional elites, and of the latter’s resulting challenge to the colonial power.

The recovery of the urban economy and the rise of a modern industrial sector had consequences on a much larger scale. During the middle part of the century, Ahmedabad progressively regained its centrality over the surrounding area. The old puras were partially revived as warehouses for merchants who wanted to store their goods outside the city limits in order to escape the payment of octroi.23 At the same time, the economic recovery of the city encouraged migrants from nearby districts to come and settle in and around the city. So, while there was an evident confrontation between local elites and colonial administrators, a more silent and implicit form of confrontation began to transform the urban space, culture and society. It was represented by the steady influx of migrants and by the unplanned and completely unserviced settlements that these masses of people created in the areas surrounding the city. Many of them sought jobs in the emerging industrial sector, but many others remained on the fringes of the city, living an always precarious existence between city and country. Irrespective of their origin and occupation, these people had no representation in the newly formed municipal bodies. The voices of the industrial labourers made themselves heard decades later, when social workers and political activists, influ...