- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Rachmaninoff's Recollections (Routledge Revivals)

About this book

This book, first published in 1934, contains the recollections of the varied and coloured life of a great pianist and composer, who is one of the most striking figures of the musical world. Rachmaninoff dictated his memoires to the author of this book, and much of the story is therefore told in the first person. The final chapter is Riesemann's own contribution. It is an estimate of Rachmaninoff's qualities as composer; it shows knowledge of all his more important works; and it shows discrimination. The whole book is an authoritative and interesting study of a popular artist.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Subtopic

Music BiographiesRACHMANINOFF’S RECOLLECTIONS

CHAPTER ONE

HAPPY CHILDHOOD IN THE COUNTRY

1873–1882

Life of the Russian aristocracy in the seventies and eighties of the nineteenth century—The parents and grandparents of the artist—First recollections of his childhood—The piano mistress, Anna Ornazkaya—The parents differ about the future of their sons—“Corps of Pages”—Fate decides—The Rachmaninoff children and their parents—Removal to St. Petersburg—Little Sergei enters the Conservatoire

THE Russia of the seventies of the last century is a vanished world, connected with the present only by feeble threads of a purely personal character. These threads reach across the borders of the country towards representatives of a generation who, although born as subjects of the all-powerful Tsar, were able to call themselves the first bourgois of the free state formed in 1917, and were then driven, or had to fly, from their native soil because they would not bow before the despotism of the mob and felt even less inclined to let themselves be morally and politically chastised, or “exterminated.”

It is indeed a vanished world, this widely hated, widely admired empire of the Tsars, a target of scorn to one, an object of love to another; abused by the envious; but always sustained by the hopes of its children. Who remembers this Russia? Who is able to conjure up from a store of personal memories the magic spell of a world so rich in treasures of culture that one might well have wondered how best to enjoy them, how best to turn them to the fullest use? Even if their value is disputed to-day, it was very real at the time.

It was the period when Russian literature, science, sculpture, and, above all, music had come to its full growth.

The natural centres of this culture were the two great cities, St. Petersburg and Moscow, where it found its fullest appreciation. Glittering St. Petersburg, with its beautiful and monumental buildings, its palaces, its Court, the wealthiest and most splendid of all times, its theatres (which have made more than one theatrical manager in Europe pale with envy), its diplomats from all over the world, the nobles of the high bureaucracy, the General Staff and the Guards, resplendent in their purple and gold, and Moscow, the very heart of Russia, quieter, but of more intrinsic worth, with its snug retreats for ageing aristocrats and great gentlemen, its world-famous university, and, last but not least, its millionaire merchants—a Moscow that was almost a state within a state and certainly a world unto itself.

But the real roots of this peculiarly Russian culture, which was largely nourished from abroad by France and also Germany, but which owed its greatest charm and power to the native element added to these foreign influences, were to be found neither in the towns nor in the cities.

These roots, spreading like a network through the whole country, lay most deeply embedded in the soil wherever low walls enclosed the shady parks of old country estates, with their melancholy nightingales singing over slumbering ponds and adding instrumental brilliancy to the orchestra of frogs. It was a time when the country, for good or evil, was almost entirely ruled by the landed aristocracy. Although serfdom had been abolished for more than ten years the patriarchal spirit—a way of thinking and living which had existed for centuries—could not be changed as quickly as the external and legal forms for a state of human and social dependence. It continued for a long time and formed the inevitable and invariable background for the fascinating picture of Russian country life.

The manor-house generally was a low one- or two-storied wooden structure, built with logs from its own forest, whose sun-mottled gloom reached up to the garden gate; roomy verandas and balconies stretched across the whole front of the house, which was overgrown with Virginia creeper; behind lay the stables and dog-kennels that housed yelping Borzoi puppies; in front of the house was a lawn, round in shape—with a sundial in its centre—and encircled by the drive; a garden with gigantic oaks and lime-trees, which cast their shadows over a croquet lawn, led into a close thicket; a staff of devoted servants who, under good treatment, showed an unrivalled eagerness to serve, made house and yard lively. The girls wore light, rustling cotton frocks, and the men brightly coloured Russian shirts and boots, which were their greatest pride. In the distance flashed the blue ribbon of a river or the mirror of a lake, surrounded by birch-trees. One drove there in a special carriage, only known in Russia, which, on account of its shape, was called a leeneyka (“ruler”), in order to bathe, or picnic, or to row on the lake whose still beauty was crowned with water-lilies. In the autumn there was hunting behind a pack of eager greyhounds on a long leash, or shooting, when, accompanied by keen pointers, one tramped over marshy meadows, yellow stubble fields, and bright woodland carpets woven by falling leaves, or took up one’s stand on brightly tinted slopes where the dogs, panting and making a great clamour, drove before them the terrified hares and foxes. Quiet evening hours, spent at the tea-table, set with all the delicacies of a Russian pantry and bakehouse, or in the library, which contained periodicals and newspapers of every country, together with the most popular Russian, French, and German books, concluded the day.

Such was the environment into which was born Sergei Vassilyevitch Rachmaninoff on April 2, 1873.

* * * * * *

Vassili Rachmaninoff, son of the landowner Arkadi Rachmaninoff and Varvara Rachmaninoff, formerly Pavlova, was a captain of the Cavalry Guards, and belonged to a distinguished family of the Russian landed aristocracy. He resigned from the army at an early age and married Lyoubov Boutakova, the daughter of General Peter Boutakov, commandant of the Araktcheyev military college in Novgorod (where he taught history), and his wife, Sophie Litvinova.

The Rachmaninoffs traced their descent back to the “Hospodars” Dragosh, who had founded the realm of the Molday and ruled over it for two hundred years (from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century). One of them had married his sister, Helena, to the son and heir of the Grand Duke Ivan III of Moscow, and it was from a nephew of the former—who was named Rachmanin—that the family took their origin. A Rachmaninoff, an officer of the St. Petersburg Guards, had keenly supported the enthronement of the Empress Elizabeth, a daughter of Peter the Great, and was rewarded for this by his Sovereign, who endowed him with the estate “Znamenskoye” in the district of Tambov. This has remained in possession of the family ever since. The district of Tambov, boasting the rich “black-earth” soil, is a fertile stretch of land between Central and South Russia. The Boutakovs were domiciled in the district of Novgorod, which is situated in the north of the empire and is poorer in soil, though rich in myths and legends.

Vassili Rachmaninoff was a brilliant officer. He had great charm of appearance, being of medium size but very broad-shouldered, dark, with fine, quick, pronounced gestures, and endowed with unusual physical strength. While in his regiment he followed the prevailing fashion and led a rather dissipated life, spending a great deal of money. In character he was inclined to indulge in somewhat fantastic day-dreams. He was always conceiving grandiose projects, usually of a business nature, which cost him vast sums of money and were either never realized or suffered a sudden collapse. Although he was very musical, he used his talent only in order to fascinate a swarm of admiring society ladies with his beautiful touch on the piano when he played opera melodies and dance tunes to them. His musical talent, however, was undeniable and he inherited it from his father. The latter, the grandfather of the Composer, a calm, dignified, and gentle man, following the family tradition, had entered the army when he was young, and fought in the Russian-Turkish War. But the army afforded him little interest. He resigned his commission early and retired to his estate in the district of Tambov, which, afterwards, he seldom left. Music was his sole ambition, and, according to the undivided opinion of his contemporaries, he was an exceptional musician and an excellent pianist. In his youth he had been a pupil of John Field, who in his turn had studied under Clementi, and had spent half his life as a piano teacher in St. Petersburg and Moscow, there establishing a unique tradition in piano playing and winning especial praise for his jeu perlé, which he passed on to his pupils. Rachmaninoff’s grandfather also distinguished himself by this manner of playing. He took it seriously and pursued his study with great devotion. Up to the very last he practised four or five hours daily, and no one was allowed, under any circumstances, to disturb him in this. The stables might be struck by lightning, his cornfields might be ruined by hail-storms, but he continued to mount his Gradus ad Parnassum without a halt. Sometimes he was persuaded to play at a public or private charity concert, and this always proved a feast for the district or the whole government. Grandfather Arkadi Rachmaninoff belonged without doubt to the highest rank of amateur musicians, a class of artists widely represented in Russia during the first half of the nineteenth century. To these belonged Oulibishev, Count Vyelhorsky, Prince Odoyevsky, Count Sheremetyev, and others. Also Glinka, Dargomyshky, and, later on, Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin, and Moussorgsky, came forth from this caste.

Lyoubov Boutakova brought to her husband, the former captain of the Cavalry, Vassili Rachmaninoff, a rich dowry consisting of four or five beautiful estates. It is probable that Vassili Rachmaninoff resigned from the army as early as he did in order to devote himself to the management of these estates; a decision which, unfortunately, soon led to very sad consequences.

There were six children of this marriage: three daughters—Helena, Sophie, and Barbara—and three sons—Vladimir the eldest, Sergei, and Arkadi, who was eight years younger, and is the only one still alive besides the Composer.

Since their marriage Rachmaninoff’s parents had resided on the estate “Oneg” in the government of Novgorod. With them, in a special wing of the house, lived the grandparents Boutakov. “Oneg” was situated on the River Volchov, that river which Rimsky-Korsakov has celebrated in his opera Sadko. The mermaid, Princess Volchova, in parting from her lover, the legendary gouslee player Sadko, begins to cry and dissolves into a river, the very River Volchov whose silver ripples divide the plains of Pskow and flow into Lake Ilmen. The surrounding country is rich in picturesque beauty that could not fail to impress the sensitive mind of the growing boy who lived in its midst. The grave northern landscape, the poetry of its unchanging rhythm, left their mark on the soul of the child Rachmaninoff and found powerful expression, convincing and alluring, in all his later work.

* * * * * *

Of his early childhood Rachmaninoff speaks as follows:

“My memory goes back to my fourth year, and it is strange how all the recollections of my childhood, the good and the bad, the sad as well as the happy ones, are somehow connected with music. My first punishments, the first rewards that gladdened my childish heart, were always linked with music.

As I must have shown very early signs of a gift for music, my mother started to give me piano lessons when I was four.

I remember that, soon afterwards, my grandfather on my father’s side announced his intention of visiting us. My mother told me he was a great musician and a wonderful pianist, and would, most likely, wish to hear me play. It is probable that she herself intended to introduce to him the talents of his promising grandchild. But first of all she took me aside, attended to my hands, cut my finger nails, etc., and made me understand that this was necessary for piano playing. The proceeding impressed me deeply. My mother’s own hands were lovely; white and beautifully kept; an example to us children.

My grandfather arrived, and I was placed at the piano, and while I played my little tunes, consisting of four and five notes, he added a beautiful and, as it seemed to me then, a most involved accompaniment. This was probably in the manner of such piano duets as the ‘paraphrases’ of the Dog Waltz or Tati-tati, composed about that time by the masters of the Neo-Russian school, amongst whom were Borodin, Cui, and Rimsky-Korsakov. My grandfather praised me and I was very happy. This was the only time that I ever saw him and played duets with him, for soon afterwards he died.

I must have made pretty good progress at the piano, for I recollect that already at the age of four I was made to play to people; if I did well, I was rewarded by all sorts of good things, which were thrown to me from an adjoining room: bonbons, paper roubles, etc. This gave me great pleasure.

If I was naughty my punishment consisted in my being placed under the piano. In like disgrace other children were put in the corner. To be put under the piano seemed to me most degrading and humiliating.

When I was four years old it was decided that I should have a piano mistress. She was found in the person of a certain Anna Ornazkaya, who had just finished her studies at the St. Petersburg Conservatoire as a pupil of Professor Cross, one of the many piano teachers invited to join the first Russian College of Music by its founder, Anton Rubinstein.

Anna Ornazkaya remained with us for two or three years, but taught only the piano. As far as I can remember we had other teachers as well; probably an alternate succession of German ‘Fräulein’ and French ‘Mademoiselles,’ who were an essential feature of a Russian country household. Although I have no definite recollection, I conclude that this was the case from the fact that, as an older boy, I must have had a fairly good mastery of the French language. After I was able to read and write, one of the punishments for a crime committed in school hours was that I had to write out upon a slate, which was then in fashion, the entire conjugation of a French irregular verb. This punishment, however, was soon abolished as being too light; consequently I must have learned French from somebody, for with our parents we always spoke Russian.

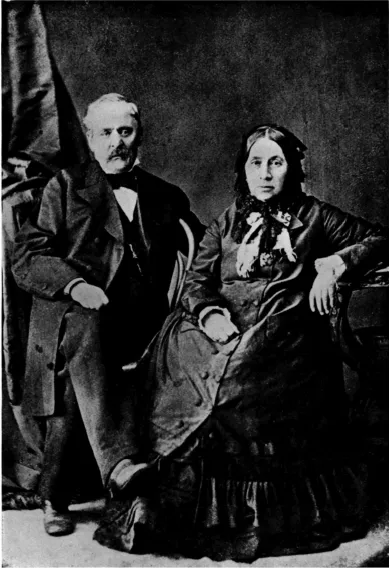

THE COMPOSER’S PARENTAL GRANDPARENTS

Thus passed the first years of my childhood. Of my parents, who often disagreed, we loved our father the better. This was probably unfair to my mother; but as the former had a very gentle, affectionate manner, was extremely good-natured and spoiled us dreadfully, it is natural that our childish hearts, so easily won, should turn towards him. Our mother, on the other hand, was exceedingly strict. As our father was generally absent, it was she who determined the routine of the household. From our earliest days we were taught that ‘there was a time for everything.’ Besides a detailed plan for our lessons, regular hours were set aside for piano playing, walking, and reading, and these were never violated except under special circumstances. This careful planning out of the day I have now, by the way, readopted, and appreciate its value more and more; but at the time I was unable to realize it and disliked the constraint imposed.

One of the arguments between my parents which cropped up repeatedly was the one concerning the future of my elder brother and myself; my youngest brother Arkadi was not yet born. My father wanted us to follow his own example and enter the army. He wished us to be educated at one of the most distinguished and privileged military colleges for officers of the Guards, the ‘Corps of Pages’ in St. Petersburg. As our grandfather on my mother’s side was a general we were entitled to enter this institution, which was only open to the select few. My mother, on the other hand, insisted on my going to the College of Music in St. Petersburg, although she did not oppose my father’s wishes in regard to my elder brother Vladimir. And the worthy Anna Ornazkaya supported her with great energy. For a long time my father remained inflexible, for he still adhered to the principle dictated—one must admit—by class prejudice that ‘pour un gentilhomme la musique ne peut jamais être un métier, mais seulement un plaisir.’ The thought that his son should become a musician was intolerable, for this ‘proletarian’ profession was entirely unsuited for the son of a nobleman.

But sometimes fate is stronger than all prejudices, and it was fate this time that decided my parents’ quarrel. When I reached my ninth year only one of my mother’s four or five beautiful estates was left in our possession. The rest had been gambled away and squandered by my father. The expensive ‘...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Preface

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Chapter One Happy Childhood in the Country 1873–1882

- Chapter Two The St. Petersburg Conservatoire 1882–1885

- Chapter Three Moscow. Sverev and Arensky 1885–1889

- Chapter Four A Dramatic Incident the Moscow Conservatoire 1889–1892

- Chapter Five The “Free Artist” in Moscow—Performance of the First Symphony and its Consequences 1893–1895

- Chapter Six Serious Mental Shock and Final Recovery 1895–1902

- Chapter Seven Growing Popularity as Composer and Conductor 1902–1906

- Chapter Eight An Idyll in Dresden 1906–1909

- Chapter Nine The Summit of Life 1909–1914

- Chapter Ten War and Revolution 1914–1919

- Chapter Eleven America 1919

- Chapter Twelve Rachmaninoff as Composer

- Note on the Family of Rachmaninoff

- List of the works of sergei rachmaninoff

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Rachmaninoff's Recollections (Routledge Revivals) by Oskar von Riesemann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.