This is a test

- 430 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

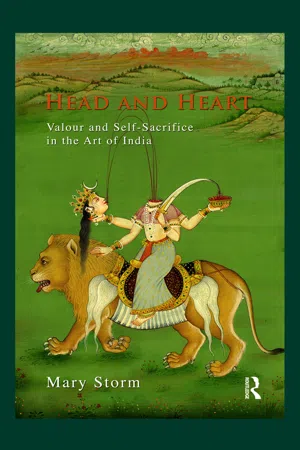

An extensive study of self-sacrificial images in Indian art, this book examines concepts such as head-offering, human sacrifice, blood, suicide, valour, self-immolation, and self-giving in the context of religion and politics to explore why these images were produced and how they became paradigms of heroism.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Head and Heart by Mary Storm in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia de la India y el sur de Asia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Images of Sacrifice

DOI: 10.4324/9781315656601-1

How and why does sacrifice move from abstract verbal concept to concrete image? Vedic religion, founded on the notions and the necessity of continuous sacrifice, was conspicuously abstract, verbal and non-visual, in distinct contrast to the enthusiastically visualised forms of later Indian religion. Vedic sacrifice put emphasis on the necessity of the perfect verbal articulation of memorised Sanskrit chants. Only the highly trained ritualists, the brāhmans, could perform the sacrifice rituals and chants. In contrast, later Brāhmaṇic and Purāṇic religion put emphasis on the universality of human-divine intimacy expressed through the sacred imagery and shared gaze of darśana.1

This difference in approach to human-divine interaction goes to the heart of the ancient conflict between the power of word and image. We may think of this as a spiritual manifestation of our cerebral dimorphism_ the rational left-brain, which controls the verbal, rational, linear processing part of the intellect; and the emotional right-brain, which controls the visual, holistic, intuitive part of the intellect together make up the whole psyche. Both aspects of the mind seek to give structure to the chaos of creation, but in radically different ways. The left hemisphere creates the taxonomy of hierarchies while the right hemisphere understands the broader gestalt in which these disparate elements create a discernible pattern of wholeness.2

Therefore, to understand the development of sacrifice in Indian religious thought it is vital to understand both the word and image of sacrifice. As Indian religious imagery developed, sculptures or paintings of sacrifice transformed the previously abstract interior world of verbal Vedic thought into the tangible exterior world of shared visual form. The process of moving from private interior, intellectual concepts of sacrifice to public, exterior, visualised concepts of sacrifice universalised and broadly socialised the intimacy of human-divine interaction by presenting a non-exclusive cultural vision of heroic self-offering. It took many centuries to move from sound to image, and to open access to the divine from Brāhman to ‘Everyman’. We must consider how historical, and especially religious, context determines our struggle to put both speech and vision at the service of existential meaning. In this long process we need to look at all images, not just those designated as artistic products of high culture.

Sacrifice: Its Meanings and Nature

All cultures have examined the desire to unite with a transcendent divine being. The desire to create and define divinity and to further understand that creation and merge the individual self with the ultimate is a compelling force shared by members of most societies. To offer oneself, or something else precious, in sacrifice has often been perceived as the surest bridge for crossing the chasm from profane to sacred.

Sacrifice explores the conundrum of how, once having created gods who are often remote, aloof or intentionally designed to be inaccessible, we are left to communicate with them. This quandary arises because divinity is often by definition and design, intended to be beyond human comprehension and understanding; yet the pre-eminent goal of religion is to define and interact with the divine. This creates a contradictory goal: how to communicate with a divine concept that can best be described as ineffable and inexpressible? By performing in the physical and spiritual lacuna between life and death sacrifice bridges the great gulf between gods and mortals.

Both the power and the problem with sacrifice is that it is a finite act. In an abstract verbal culture the problem arises of the long-term resonance of the sacrifice act. If the sacrifice ritual takes place as the transactional bridge determined by the performance of words, how does the act resonate past the point of the last tonal vibration? Thus, how can sacrifice gain and maintain permanent value? In Vedic culture this problem was addressed by the necessity of constant perfect repetition of ritual. In Brāhmaṇic and Purāṇic culture the human divine transaction shifted from the controlled yet ephemeral world of the spoken word to the less structured yet more permanent world of image.

Most religious traditions have explored the use of sacrifice as a means of communication. The Western and Indian sacrificial traditions share many elements but are different in outlook. Western sacrificial traditions have sought to use sacrifice for propitiation, redemption and thanksgiving, while Indian religious practice has used sacrifice more often for creation and renewal.3 In Abrahamic concepts of sacrificial relationships the offerant is linked in a vertical chain of privity, from man to God, but in Vedic sacrifice the offerant is connected to numerous gods in multiple systems of privity, both horizontal and vertical. Vedic sacrifice was used to replicate and control a creation with a multiplicity of divine factors. The goal of Vedic sacrifice was rarely a simple appeasement or thanksgiving to a single exterior force.

In India the process of sacrificial integration changed over the centuries. In the Ṛg Vedic period (ca. 1500–1200 bce) the sacrificer approached the divine through hymns and prayers, which culminated in the sacrificial ritual. In the Brāhmaṇic period (ca. 800–600 bce) the sacrifice itself invoked and gave reality to the gods. In the Purāṇic period (ca. 400–1200 ce) integrative communication with the divine was achieved through the development of the charismatic worship and the offering and receiving of prasāda (gracious gift). Prasāda marks the symbolic gifting substitution of non-violent fruits, flowers and foods as replacement for the killed oblations of violent sacrifice.

The structure of the word ‘sacrifice’ has different roots in India and in the West. The English word ‘sacrifice’ is derived from the Latin term sacrificium; which is derived from two Latin words: sacer meaning ‘holy’ and facere, ‘to make’. It is the source for our word ‘sacred’. Therefore, sacrifice in the Western sense means the process of making sacred. The Sanskrit words yajña or balidāna, which are both translated as ‘sacrifice’, have other connotations. Arthur Anthony Macdonell defines the term yajña as the sacrificer, as well as the sacrifice, oblation or offering. This definition emphasises the primal wholeness of the ritual, in that the act and the performer are understood to be one. Yajña seems to be concerned with the entire sacrificial concept and process and embraces both the ritual and the ritualist. Macdonell defines the word balidāna as the presentation of an offering or oblation;4 balidāna is thus limited to the sacrificial gift giving, which is perhaps closer in meaning to the English ‘sacrifice’. In modern Hindi the verb balidenā is usually, but not exclusively, linked to the giving of blood sacrifice.5 The noun balí in Hindi refers to the blood offering, as opposed to the vegetarian offering and receiving of prasāda.6

‘Sacrifice’ and ‘offering’ are often used interchangeably, but the ritual intentions expressed by the two words are different and are so distinguished in Sanskrit. Jan van Baal notes the distinction as follows: ‘I call an offering every act of presenting something to a supernatural being, a sacrifice an offering accompanied by the ritual killing of the object of the offering’.7 In sacrifice, the offerant must remove something from his own sphere of control and wholly transfer it in a ritual manner to a supernatural recipient. The unique aspect of the sacrificial gift is emphasised. For example, when sacrificing a life, it is the uniqueness and finality of the sacrifice that gives it value. An offering, though valuable, is either made of renewable materials, or is a reproducible act.

‘Oblation’ is another common English synonym for ‘sacrifice’, and has a slightly different connotation. ‘Oblation’ derives from the past participle stem of the Latin verb offene — to offer, or bring forward. An oblation is a religious, ritual offering, but its first received definition implies the sacrifice of a non-living offering. The term is also acceptable as a synonym for the sacrifice of a living being. This is now a secondary definition, and intimation that at one time living sacrifices were common. It is noteworthy, however, that the related term ‘oblate’ refers to a person offered or dedicated to the religious monastic life, one whose life is a form of living sacrifice, and a reminder perhaps, that the notion of sacrifice has so evolved that a life dedicated to spiritual goals rather than material aims, is considered an abnegation of self.

Shared Aspects of Sacrificial Traditions

When one uses terms such as ‘sacrifice’, ‘offering’ or ‘oblation’, problems of definition surface and linger. Such English words come to many of us freighted with the notions of the Biblical or Christian sacrifice. Indian sacrifice shares with other traditions the basic elements of the ritual: (a) an offerant who arranges for and pays for a sacrifice; (b) an officiating sacrificer (who may sometimes be the same person as the offerant); (c) a victim (the object of the sacrifice, in the case of self-sacrifice the victim is also the offerant); (d) a method of transference; and (e) a divine recipient. Indian sacrifice, while sharing these external components of other traditions, is at its conceptual centre, distinct. Before distinguishing the differences between it and other religious sacrifice rituals, it may be useful to consider the similarities among religious traditions.

Sacrifice as a Transactional Bridge

There are many distinctions in the rituals and philosophies of the different systems of sacrifice, but there are also important shared characteristics. There are five major areas of shared characteristics in the world’s many sacrifice traditions. First, sacrifice was always used as a transactional bridge between offerant and deity. It was the vehicle of communication between humans and gods. It is often the primary and foundational ritual in a religious tradition, the first step taken by a human being in the journey toward understanding and connection with the perceived greater reality. Many scholars have studied the structures of sacrifice as the foundations of religious and philosophical speculation. Emile Durkheim,8 Sigmund Freud9 and Max Weber10 described sacrifice and the sacrificial meal as the origin of community and civilisation. Sacrifice is a formalised recognition a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Plates

- Glossary

- Foreword by Serinity Young

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The Images of Sacrifice

- 2. Human Sacrifice from Myth to Reality: The Integration of Tantra

- 3. Distinguishing Suicide from Self-Sacrifice

- 4. Symbols of the Body Offering

- 5. The Gods who Receive Sacrifice

- 6. The Heroes who Self-Sacrifice

- 7. The Historic Setting for Self-Immolation

- 8. Death and Remembrance

- 9. Motivations for Abandonment of the Body: Political and Military

- 10. Motivations for Abandonment of the Body: Health and Society

- 11. Chinnamastā: Divine Reciprocity

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Select Bibliography

- About the Author

- Index