![]()

Education that doesn’t pay!

In April 2003, a troubling story rocked Egypt. After graduating from the prestigious Faculty of Economics and Political Science at Cairo University, a self-made young man from the provinces, Abdel Hamid Sheta, had applied to the Ministry of Foreign Trade but was denied a position there because he was socially unfit – his father was a poor farmer. Devastated by the rejection and apparent meaninglessness of his hard-earned educational qualifications, he committed suicide by drowning himself in the Nile.

(Singerman, 2007, p. 33)

The story of Abdel Hamid Sheta reflects the intersection of many factors that have led to youth frustration in Arab countries. Lack of opportunity, nepotism, and class discrimination are some of these factors. I saw Sheta myself in the Faculty of Economics and Political Science, Cairo University, where I undertook my BSc in Political Science. He was only one year ahead of me. Although we never talked, I saw him a few times at school after he graduated. He worked as a research assistant in one of the research centers at school, while studying for the Ministry of Foreign Trade exams. He was very energetic, smart, timid, and polite.

His academic excellence and passion for work were not enough to provide him with a decent living. Employment opportunities were limited, and he had to accept the low salary of a research assistant while pursuing his dream of joining the Ministry of Foreign Trade. But as the story goes, being the son of a farmer prevented him from ascending the social ladder, and he was denied a job in the ministry. His education would not allow him an opportunity in the private sector either, where the demand for jobs is higher than the supply and nepotism or wasta (literally meaning middleman) is essential to obtaining a job. Faced with all these closed doors, the dreaming young man chose to end his life.

The story of Abdel Hamid Sheta is similar to the stories of thousands, even hundreds of thousands of young people everywhere in the Arab world. Education raises their expectations, but it does not give them the skills needed for private-sector employment, while the public sector keeps shrinking as governments move toward market economies. In both cases, meaningful employment opportunities that provide a reasonable salary to support a decent living are almost absent. The fact is that the social, economic, and educational systems are not ready to absorb the dreams of young people and turn them into a productive output.

This chapter tells two stories about Arab countries: the first is the story of economic performance, characterized by volatility between high and low growth rates, directed mainly by oil prices. The second story is that of education expansion, which achieved large gains in terms of quantitative measures, but little in terms of quality. This portrayal aims at highlighting the lack of a concrete link between the economy and education expansion.

The region as a whole achieved high growth rates during the 1960s and 1970s, a development driven mainly by the oil boom of the 1970s, but had stagnated from the mid-1980s with the collapse of the oil boom until the early 1990s. Some countries in the region have resumed economic growth since the mid-1990s, especially after the rise in oil prices in 1998 (Elbadawi, 2002).

One main observation from tracking this developmental path is that education and economic performance in the Arab world do not seem to be related. While economic performance fluctuated widely since independence, spending on education kept increasing regardless of economic performance (The World Bank, 2008).

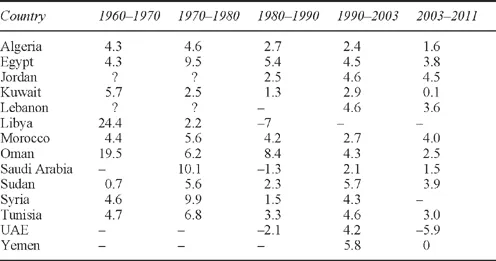

Table 1.1 shows the shifts in GDP per capita since the 1960s until 2003 for selected Arab countries. The table shows that the era of the oil boom (the 1960s and 1970s) witnessed high growth rates, especially given what could be called the “spillover effect” of oil prices to non-oil-rich countries where labor remittances, investments, and aid from oil-rich Arab countries contribute to growth. After the 1970s, there was a drop in growth rates for almost all countries in the sample. Some countries were able to resume their earlier growth and some did not. However, and despite these variations, in no country was the growth in output sufficient to keep up with labor growth, much less to significantly raise real wages (Richards & Waterbury, 2008). This volatility as well as variation in growth directs attention to the important question about whether growth in the Arab world is based on firm foundations of human capital and whether the wealth and accumulation of resources achieved in a number of Arab countries such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Qatar can be sustained in the future.

Table 1.1 Growth of GDP per capita for selected Arab countries, 1960–2011

Source: World Bank Development Indicators 2005.

Notes

Adapted from Richards and Waterbury (2008).

Figures for 2003–2011 are from World Development Indicators 2014.

The economic story: volatility, oil, dependency, and

unsatisfactory growth

In this section, I show evidence and cite various explanations for the economic fluctuations briefly cited above. As previously noted, the Arab region as a whole achieved high growth rates during the 1960s and 1970s, but had stagnated from the mid-1980s with the collapse of the oil boom and until the early 1990s. Some countries in the region have resumed economic growth since the mid-1990s, especially after the rise in oil prices in 1998 (Elbadawi, 2002).

The overall growth performance in the region has been mixed and characterized by higher volatility compared to other developing regions. Declining from heights averaging 8.7% during the 1970s, growth rates tumbled to an average of 1.5% during the 1980s. Toward the end of the 1980s, which has been described as a lost decade, a number of Arab countries embarked on programs for economic reform and structural adjustment with considerable variance in the pace and depth of these reforms. As a result, GDP growth in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region picked up during the 1990s, averaging 3.9%. In the 2000s, a wider range of reforms were undertaken and, despite the slow pace of reform, the growth pay-off was reasonable, especially given the rise in oil prices. Growth rates averaged 5.1%, but the region remained lagging behind in terms of economic growth compared to other regions (Mottaghi, 2009). Figure 1.1 shows the fluctuation in GDP growth rates in the MENA region.

Figure 1.1 shows the volatility characteristic of Arab economies. While the figure shows data for the decades since 1971, annual data shows an even higher degree of unpredictability. The Arab Human Development Report 2009 (UNDP, 2009) pinpoints this volatility by describing the annual growth curve in the Arab region as riding a rollercoaster, which swings with changes in oil prices. In attempting to explain this phenomenon, Makdisi, Fattah, and Limam (2005) argued that capital in the MENA region is less efficient, the natural resource curse more pro...