![]()

1 Introduction

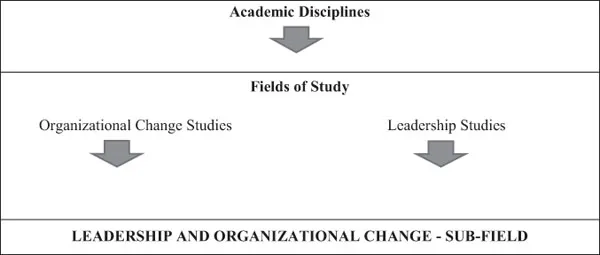

The leadership of organizational change has been the zeitgeist of recent decades, developed around a narrative of organizational change as the problem and leadership as the solution. Politicians and policy makers, regardless of political allegiance, look hopefully towards leaders who are literally transforming public institutions. Similarly, private sector shareholders look hopefully towards their chief executives to realise their aspirations and radically restructure organizations. The leadership of the organizational change process never seems to fail, with failure instead attributed to the failure of the leader/s. These perceived individual failings are ritualistically and symbolically celebrated through the dismissal and replacement of leaders. Belief in the leadership of organizational change is part of a broader shift from management towards leadership; ‘leadership rather than management is currently advocated in the mainstream management literature and organizational policies as the key to effective organizational performance’ (Ford and Harding, 2007:475). It is a shift that privileges leadership and simultaneously disparages management. For example, Riggio (2011:120) writes about ‘when the field of management began to make the shift from viewing those in positions of power and control as mere “managers” to viewing them as taking on higher-level “leadership” activities…’ And Grint (2005:15), although sceptical, acknowledges the role subordination implied within leadership and management differentiations with the implication to ‘… get out of management and into leadership!’ Gradually and imperceptibly, the word ‘leader’ has replaced the word ‘manager’ (Salaman, 2011). This practical interest in the leadership of organizational change has been mirrored by considerable interest in the fields of both leadership studies (Grint, 2005) and organizational change studies (Thomas and Hardy, 2011), with the focus of this critical review narrowing to the sub-field of leadership and organizational change. In Figure 1.1, the leadership and organizational change sub-field is depicted as being informed by both the fields of leadership studies and organizational change studies, with both fields informed by many different disciplines.

The implication of Figure 1.1 is that attempting to understand the sub-field of leadership and organizational change from either a leadership studies perspective or an organizational change perspective will be incomplete. However, the academic norm is to specialise within a specific field, which may partially explain why academic progress in understanding the sub-field has been so limited. As Bryman et al (2011:ix) suggest with regards to leadership, ‘[P]recisely because it is such a productive field, it is difficult for even specialist scholars to keep up with its breadth and it is even more difficult for new scholars to break into it.’ Figure 1.1 also suggests that understanding the sub-field of leadership and organizational change will be informed by many competing paradigms, philosophies and perspectives characterising both fields of study, as well as the academic disciplines informing these fields. The leadership of organizational change may be the zeitgeist of recent decades, but that does not equate necessarily to understanding. The understanding of the leadership of organizational change to date may be characterised as a seduction and leadership, as a seduction is nothing new (Calas and Smircich, 1991). In this instance, the leadership of organizational change rhetoric may even exceed/exaggerate the reality.

Figure 1.1 Levels of disciplines, fields and the sub-field

This critical review of the leadership of organizational change goes back to the future in order to understand the fields of study, academic debates, values, beliefs and assumptions underpinning today’s leadership of organizational change. A particular emphasis is placed upon social construction (Berger and Luckmann, 1966) and discourse (Fairhurst, 2008) in the belief that leadership is primarily concerned with managing meaning (Pondy, 1978). As a consequence, the label ‘the leadership of organizational change’ seeks to reference contemporary discourses and debates, speaking to ongoing contemporary debates regarding both theories and practices. This label even has assumptions embedded within it that leadership will result in successful organizational change, which will be achieved in a rational and linear manner. However, at times, an alternative ‘leadership and organizational change’ label is used in order to avoid at least some of the progressive assumptions embedded within leadership language. Organizational change may necessitate different forms of leadership, and through organizational change, leaders and leadership may change. The second label is believed to avoid some of the forward-facing linear rationality of the first label.

In this introductory chapter, the historical perspective adopted towards leadership and organizational change is introduced, as well as the process and content of the critical review of leadership and organizational change. The language, landscape, boundaries and map of the book are introduced in terms of defining key terms, what is included and excluded and briefly mapping the content of the subsequent chapters.

Forward to the Past or Back to the Future?

Whereas societal belief in the transformational capabilities of leaders goes back centuries, pragmatically, this critical review focuses on the last 35 years. Burns (1978) believed that leaders in collaboration with followers could transform institutions and societies, and this belief offered the inspirational starting point for this review. Rost (1997:5) reflected back upon Burns’s achievement as a way ‘…to redefine leadership around a political frame of reference, and present to his readers a whole new way of looking at leadership as transformational change.’ The review concludes at the end of 2014 with economies, societies, organizations and individuals still suffering the consequences of 2008’s potentially leadership-related global financial recession.

…some of our dominant theoretical concepts—such as transformational and charismatic leadership—have legitimised an over concentration of decision making power in the hands of a few, with consequences that have been less than socially and economically useful.

(Jackson and Tourish, 2014:4)

Burns (1978) originally appeared to have been attempting to shame leadership studies out of its complacent orthodoxy, describing the study of leadership as suffering from intellectual mediocrity. He constructively offered a lengthy account of how institutions and societies could and should be transformed through ethical leadership, which was more closely aligned with political science, rather than management and organization studies. Burns believed that democratic and egalitarian forms of leadership were capable of transforming institutions and societies. Burns’s book was primarily a study of followership, as Burns believed that followers were crucial in terms of democratic/egalitarian changes in societies and institutions. However, unfortunately, scholars have focused too narrowly upon Burns’s differentiation between transactional and transformational leaders. His pioneering work on followership, the distinction between reform and revolution and their interplay was ‘lost in the translation’ into leadership orthodoxy. The 35-year review window includes increasing engagement with leading change (Kotter, 1996/2012) and transformational leadership (Bass and Riggio, 2006), as Western businesses responded to competition from the East. The 35-year window also includes the 2008 global financial recession, and the opportunities that have arisen to question leadership in general and the leadership of organizational change in particular.

Grint (2008) concluded his own review of leadership studies by critically questioning the tendency of leadership to go forward to the past. He argued that despite the apparently forward-looking developments within leadership studies, these developments reflected and revisited earlier preoccupations. Today’s contemporary language of inspirational, transformational, visionary and charismatic leadership revisits the earlier, discredited traits approaches, still encouraging individualistic and heroic conceptions of strong leaders. In the case of the leadership of organizational change, forward-looking rhetoric magnifies what Grint was encountering within leadership studies. Leadership of organizational change language and debates look positively and proactively to imagined futures. As Kotter (1996:186) concluded in Leading Change, ‘… [P]eople who are making an effort to embrace the future are a happier lot than those clinging to the past.’ One of the dangers of going forward into the past is that potentially the past and earlier learning is lost with those who forget the past condemned to repeat the past (Santayana, 1998). However, looking to one of the key contributors to the debates featured in this critical review, Kotter (1996:142) explicitly expressed his irritation with corporate history in Leading Change, writing, ‘[C]leaning up historical artifacts does create an even longer change agenda, which an exhausted organization will not like. But the purging of unnecessary interconnections can ultimately make transformation much easier.’

Today’s strong, individualistic, heroic, masculine notions of leadership (often also associated with organizational change) unfortunately begin to resemble the ‘Great Men’ leadership theories of earlier centuries and have forgotten the past, which is now being proactively and positively repackaged and revisited upon societies, institutions and individuals. Yet, beneath this enthusiastic, forward-looking rhetoric, gendered leadership inequalities (Alvesson and Billing, 2009) are very prevalent. There is an absence of ethical change leadership (By et al, 2012,2013; By and Burnes, 2013) and a broader movement towards more democratic and egalitarian leadership (Burns, 1978; Rost, 1993) beneficial to wider societies is postponed, possibly indefinitely. As a counterbalance to today’s troubling forward-to-the-past trajectory, Grint (2008:116) encouraged going back to the future

…to see how those futures are constructed by the very same decision-makers and consider the persuasive mechanisms that decision-makers use to make situations more tractable to their own preferred form of authority.

Again, this is particularly relevant to the leadership of organizational change and the persuasive, forward-looking discourses that leaders and mainstream academics employ. These accounts go back further and are far wider than organizational change: ‘… [W]e are told wonderful stories about the role that great leaders have played in making history and initiating the changes that have created the world as we know it’ (Haslam et al, 2011:1). Whereas the leadership of organizational change captures the organizational imagination today, early forms of leading change within societies and within institutions go back centuries, informing both the early and more recent development of civilisations. In a similar manner, textbook orthodoxy reassuringly depicts leadership studies historically developing over the past century, implying the successful advance of knowledge (see Cummings, 2002 for a critique). Grint’s (2008) overview of leadership literature focused upon a more recent epoch between 1965 and 2006. Initially, Grint revisited the 1800s and the ‘Great Men’ accounts of leadership prior to 1965, which depicted leadership as masculine, heroic, individualist and normative, a depiction that prevailed into the 1900s and unfortunately still exists to this day. Grint critically reviewed management and organizational studies developments through the 1900s, bringing the story up to date with the contemporary arrival of transformational and inspirational leadership. Grint (2008) feared that despite all the inspiring visions and missions, there had been a return to earlier normative trait approaches and that we had gone forward to the past. In critically understanding leadership and organizational change, such inspirational missions have a shadow side:

…[K]nowledge—what counts as “true”—is the property of particular communities and thus that knowledge is never neutral or divorced from ideology.

(Grint, 2008:109)

A further advantage of this 35-year window is that it allows for the consideration of early conceptualisations of the leadership of organizational change, which used to feature strong leaders making tough decisions. Bennis (2000:114) parodies such enduring conceptualisations:

But even as the lone hero continues to gallop through our imaginations, shattering obstacles with silver bullets, leaping tall buildings with a single bound, we know that’s a false lulling fantasy and not the way real change, enduring change, takes place. We know there is an alternative reality.

Once again, the shortcomings of leadership orthodoxy are highlighted, although unfortunately, the lone hero still to this day gallops through many people’s imaginations, with gunfights still to be won and cowgirls (and cowboys) still to be saved. More importantly, the criticism of leadership that Bennis implies helps make sense of the recent attempts to rethink leadership. Acknowledging the centrality of followers (Grint, 2005), gender and leadership differences (Alvesson and Billing, 2009) and the goal of leading change ethically (By and Burnes, 2013) all make greater sense when understood as attempts to address earlier leadership deficiencies, rather than as extensions of earlier leadership thinking. As well as being proactive attempts to lead organizational change in a more moral and inclusive manner, they offer critiques of the past conceptualisations of leading organizational change.

In critically reflecting back on the past 35 years, this review takes in the eighties and early attempts to manage organizational change, particularly cultural change, which failed to meet the unrealistic expectations placed upon such change initiatives (see Deal and Kennedy, 1999 for a critique by the original proponents of cultural change). Whereas the failures in delivering on these unrealistic expectations are not disputed, the rational, linear and unambiguous managing-change mindsets informing theory and practice are disputed, and will be discussed in terms of the competing perspectives, paradigms and philosophies of organizational change (see Chapter Three).

In looking back to the nineties, leading change became the new managing change with a tangible shift from managing organizational change towards leading organizational change. It will be necessary to revisit this shift with the benefit of hindsight, as this shift informs today’s leadership of organizational change discourse (see Chapter Four for further discussion). In the interim, as this perceived shift was a major driver for writing this book, it was surprising to learn that two American billionaires (Ross Perot and J.D. Rockefeller) played an explicit role in encouraging the shift, with their wishes subsequently championed by Harvard Business School professors. Influential publications relating to management and leadership differentiations were reviewed and perversely, the anticipated evidence base informing the significant shift from managing change to leading change integral to this story does not exist (discussed further in Chapter Four and Six). Rather, it remains another of the ass...