- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About This Book

Gender relations are in a period of transition. In this collection, some of Australia's leading writers and talented young scholars offer a systematic overview of the ways in which recent feminist analysis is shaping women's studies. They reflect on questions of power, difference, social structures, methodology and culture. They ask how feminism has changed in the past few years, and whether concepts like 'patriarchy' and 'oppression' are still relevant.Contributors include: Ien Ang, Julie Ewington, Jill Matthews, Susan Sheridan, Sophie Watson and Anna Yeatman.'All the liveliest feminist debates - postmodernist, deconstructionist, post-Marxist - are represented here. The scope is broad and the subject matter multidisciplinary. This book is new Australian feminism at its newest and best.' - Michele Barrett, Professor of Sociology, City University, London

Frequently asked questions

Information

1 Women's studies, feminist traditions and the problem of history*

Table of contents

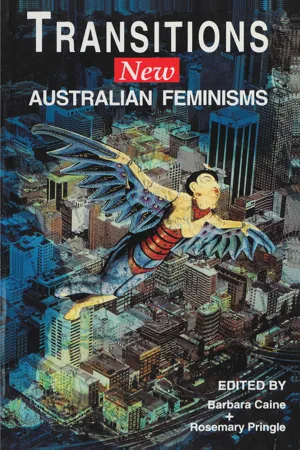

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Introduction

- 1 Women's studies, feminist traditions and the problem of history

- 2 Feminism and method

- 3 Knowing women: The limits of feminist psychology

- 4 Interlocking oppressions

- 5 I'm a feminist but . . . 'Other' women and postnational feminism

- 6 Dancing modernity

- 7 Reading the Women's Weekly: Feminism, femininity and popular culture

- 8 Number magic: The trouble with women, art and representation

- 9 Keys to the musical body

- 10 Writing/Eroticism/Transgression: Gertrude Stein and the experience of the other

- 11 Of spanners and cyborgs: 'De-homogenising feminist thinking on technology

- 12 Reclaiming social policy

- 13 Beyond patriarchy and capitalism: Reflections on political subjectivity

- 14 Rethinking prostitution

- 15 Destabilising patriarchy

- Notes

- References

- Index