eBook - ePub

Writers & Their Milieu

An Oral History of First Generation Writers in English, Part 1

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Writers & Their Milieu

An Oral History of First Generation Writers in English, Part 1

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Within the pages of this volume run writers and their lives, writers and their works, writers and their readers. Anyone seriously interested in the history, development, and future of Philippine literature has no choice but to submerge himself in the now shallow, now deep waters of reminiscences and recollections, self-appraisals and gossip, regrets and successes. Featured Filipino writers in English in this volume: Paz Marquez Benitez, Casiano T. Calalang, Luis G. Dato, Angela Manalang Gloria, Leon Ma. Guerrero, Maria Kalaw Katigbak, Fernando L. Leaño, Maria Luna Lopez, Salvador P. Lopez, Arturo B. Rotor, Bienvenido N. Santos, Loreto Paras Sulit, Jose Garcia Villa, and Leopoldo Y. Yabes.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Writers & Their Milieu by Edilberto Alegre, Doreen Fernandez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Creative Writing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Bienvenido N. Santos, who graduated from the U.P. a month after this story was published.

BIENVENIDO N. SANTOS

Bienvenido N. Santos (1911-) has been unjustly known only as the chronicler of the Filipino exile in the United States. He is basically a poet, a love poet who speaks of having been clawed by love. Ben charts the geography of passion, sex included, as no Filipino poet-novelist ever has. His short stories are flashes of complete moments, mostly of solitude and sadness. His novels are explorations of those moments, textured with the voices of the flesh, the conjugation of yearning.

Perhaps it was his having been orphaned early that shaped the aloneness, the exile of his stories. Some of his characters are so alone that even in the act of love-making, they are exiled unto themselves. And perhaps it is also Ben’s innate sadness that makes him such a wit, such a humorist—for that establishes distance. And his affable smile disarms. He is cherubic that you cannot dislike him.

Yet Bienvenido Santos is a very serious writer, the writer compleat—writing is all that he knows. And he does it well. His is not the analytical mind of Western logic; his is the intuitive perception—subjective, personal, and in its own peculiar way, uncannily analytical. His mind cannot pare down a character or a plot to its component elements. He grasps characters and events as wholes. And that is how his characters throb—as the hearts of men alive, desperately wounded since they feel as whole beings, keen to sorrows, prey to others’ betrayal and violence.

Passion is Ben Santos’ turf. Love is his one consistent concern, he has told us. He has followed it from the juvenile pratings of a young adolescent in his early poems and short stories, to the unabashed description of sweating loins and gasping breasts. But the physical passion in his works, like onanism, exiles the man; only love blesses it as communion. That makes him a romantic. And that is the basis of the sadness and the solitude of the Pinoy in the U.S.—he is disconnected, he is not blessed, he is not in communion. This makes him both a lover hungry for affection and a sad person vulnerable to the slightest show of concern.

Wherever Ben goes, he attracts a coterie of idolaters. In Daraga, a business tycoon and a Ukrainian mestizo who were his former students jog with him at daybreak. Before he left for the U.S., a despedida was hosted by other former students, who recited poetry they had learned in his classes. During his latest book launching, former wards of the 60s appeared not only to listen to him and buy his books, but to hold his hand.

This is because Ben is, at the core, a soul who cannot be corrupted by wealth and attention; a man who cannot be disliked, for while he is very physical, he has no malice. He has remained childlike. That, perhaps, is why and how he has been able to explore our loneliness, our aloneness, and our passions.

BIENVENIDO SANTOS

San Juan, Metro Manila

24 November 1981

ENA: Why do you write in English?

BNS: Americans have asked me that, and I’ve felt affronted. I said, why not? I explained to them that in the first place, I am not a Tagalog; I’m from Pampanga. Yet I have not read anything in Pampango. I studied in English, of course, and I think I fell in love with the sound of the English language. This is true. Tom (my son) helped me analyze myself in this. When I tell this to the Americans they laugh, “Our language sounds good?” But really, I fell in love with the sound of English. For a long, long while, because all sounds follow a pattern, we memorized all our prayers in Spanish. We may not love the sound of Spanish, but we knew we were conversing with a deity we believed in. In my simple mind, this was His language, and no other language was going to be understood. It’s almost paganistic. Anyway, I prayed in Spanish, yet I didn’t understand what I was saying. “Bendito y alabado sea el Santissimo Sacramento del Altar, y la Virgen Maria, Immaculada Concepcion, divina gracia, madre de Dios, señora nuestra concebida sin mancha de pecado original desde el primer instante de su ser natural.” But in English—I don’t know what the Americans did, but in my time they seemed to give us all the American authors known for their musicality. And who cared what they were saying, as far as we were concerned? We were forced to memorize poems that had rhyme. We memorized Longfellow.

ENA: Did you also have to memorize “Thanatopsis?”

BNS: Oh yes, yes. What was the last part again?

“So live, that when thy summons comes to join

The innumerable caravan, which moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not, like the quarry slave at night. . . .”

Ang sarap! talagang masarap! And by that time I

Was already getting the impact of the poem’s metaphor. I already knew about a caravan then.

“Scourged to his dungeon, but sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.”

Ang sarap! Tom explained to me: “Dad, this is the transition from sound to meaning. That is why your English is good. You really earned it. And what you have to pay for the mechanics is your love for it.”

ENA: Sound to meaning, that’s really James Joyce. “In the beginning was a moo cow.” That first paragraph of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is all sound.

BNS: Yes, especially in his other works. I love James Joyce.

ENA: I would like to confirm the story that you had Joyce’s Ulysses with you when you crossed to America for the first time.

BNS: That’s what I read all the way to America—the only book I had.

ENA: That has become a legend among the young writers.

BNS: The one who knows about that is NVM (Gonzales). When I was studying, I once took Finnegan’s Wake in class for one semester. I didn’t understand a thing, but I loved the instructor—Mary Colum, the wife of Padraic Colum. I think I enjoyed myself because I was not working for a degree. I was there to absorb, and boy, did I absorb. I wanted to be a writer.

ENA: You had earned your BSE by then?

BNS: I had finished my master’s degree. My experience was a common one among Filipinos who used the language, and so I stopped worrying about myself.

ENA: I also think, however, that in your generation there was a direct connection between the United States and the Philippines in terms of cultural diffusion. You were using American textbooks, and it was later that the Camilo Osias Readers were developed; then came the gradual shift to Philippine Prose and Poetry, volumes 1 to 4. And so in my generation we received a completely different kind of English from yours, because we were not using American textbooks any longer. The English was different.

BNS: Is that why my generation did not react to American education the way you are reacting now?

ENA: For us the question of education is a question of identity. That has become quite clear to us and you were not yet, I think, concerned with the question of identity, since actually you had no problems with the United States. After you, we had problems.

FOLIO TWO

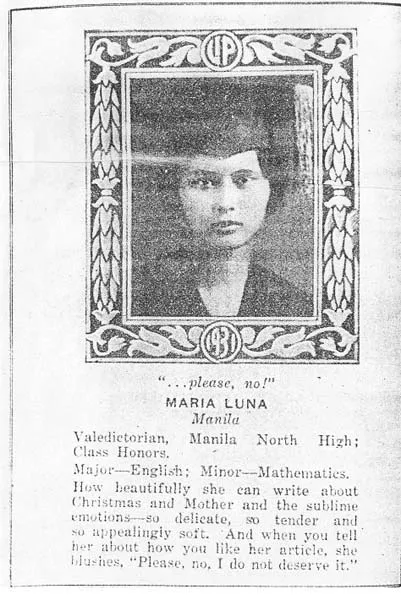

MARIA LUNA LOPEZ

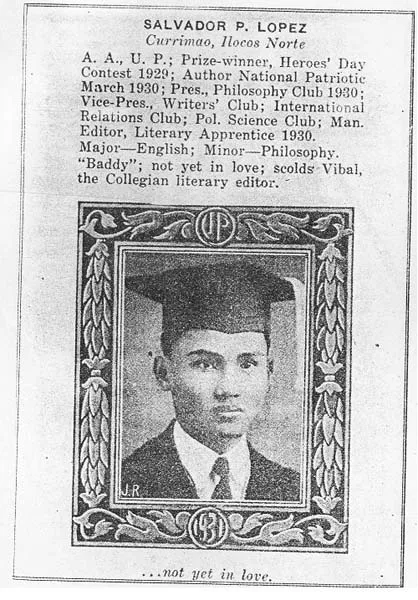

SALVADOR P. LOPEZ

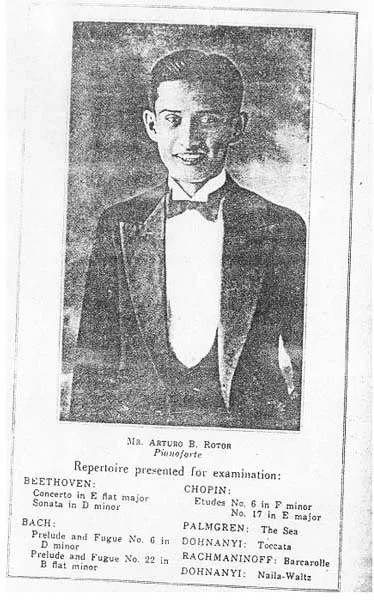

ARTURO B. ROTOR

BIENVENIDO N. SANTOS

LORETO PARAS SULIT

JOSE GARCIA VILLA

LEOPOLDO Y. YABES

spouses, Maria Luna and Salvador P. Lopez.

Dr. Arturo B. Rotor photographed for the program of his graduation recital at the U.P. Conservatory of Music.

S.P. Lopez is conferred a gold medal as outstanding alumnus by then U.P. President Bienvenido M. Gonzales for having won the 1940 Commonwealth Literary Award for the essay. At right is Manuel Arguilla, who won the same award for the short story.

The Philippine Herald gave space and importance—note the signatures—to quality short stories, such as these classics: Loreto Paras Sulit’s “Harvest” and A.B. Rotors “Zita”.

Bienvenido Santos in 1932 with a sonnet.

Loreto Paras Sulit, U.P. coed in the 20s.

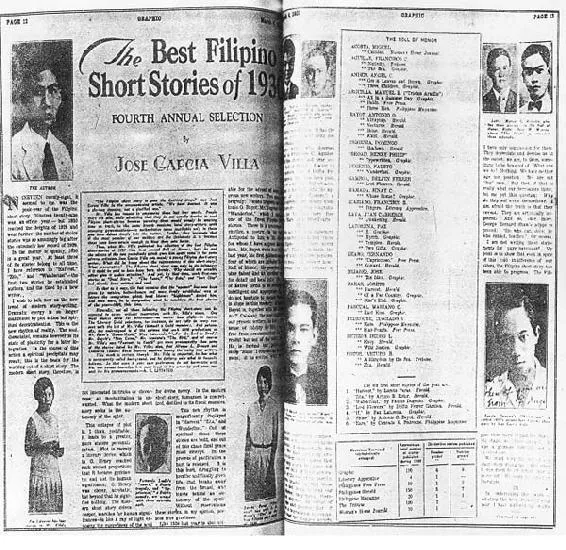

One of the driving forces for the short story in the 1930s was the annual selection of “The Best Filipino Short Stories” fearlessly made and commented upon by Jose Garcia Villa, and published in the Graphic.

Although Jose Garcia Villa, erstwhile U.P. medical student, was often considered as being in a special category as a writer and as a critic, occasionally others disagreed with him publicly, as N.H. Guerzon did.

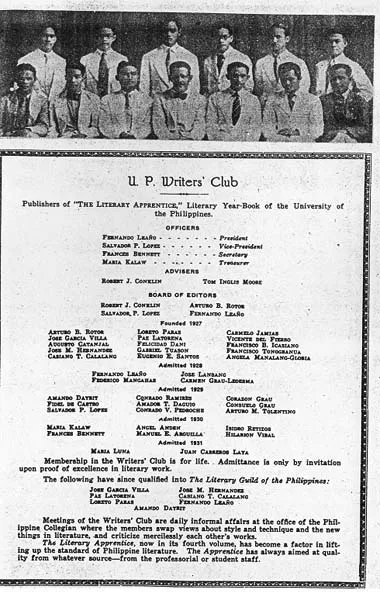

Philippinensian, 1931

One among numerous Santos stories published in the Graphic

BNS: We too had problems with the U.S. then. But we did not negate the language we were taught in, and it didn’t matter that we were speaking in English. As a matter of fact, we felt that it was an advantage, because we spoke their language, and we could tell them what we really wanted to say. After World War II, for instance, we were not going away from English, but making English a tool for expressing our feelings. Last night I was troubled, because I didn’t know most of the people (at the party at La Solidaridad Bookstore). It seemed that I had stayed away too long, and had come back a stranger. Ang lungkot ko kagabi. I felt even more of a stranger because I should have known their faces. Even my contemporaries—I could not recognized some of them, because some have changed. Even Franz (Arcellana) seemed older that I remember. The only thing I remember about all of them is their voices. I knew Arcellana because of his laughter. Someone came up to me last night, and I thought it was a woman. But at the voice, I said, “This is Epistola.” I did not recognize him until I heard his voice—perhaps because his hair was long. I said to myself, what’s happening? I remember their voices but not their faces. I know eleven years is a long time. When I was here in 1970, I did not see them, because I was in Bicol.

DGF: You may not remember them, but they remember you. And those who don’t know you feel that they do, because of your books. That is why they were there. Those P.E.N. meetings are not usually that well-attended—but this was for you.

BNS: Anyway, I had trouble remembering. I spoke in a very low voice because I could not raise it. That is why they had to be very quiet, if they wanted to hear me. I wrote “The Stragglers,” you know. We were the stragglers—that is the word I was looking for last night. After I talk, I remember things I should have said. Sometimes I am happy I did not remember. One of the things I remembered last night was that we—the older guests—were classmates. But they were already publishing when I was not. They were already well-known—S.P. Lopez, Maria Kalaw Katigbak, Maria Luna, Conrado Ramirez, Kayanan, Fernando Leaño. I was a nobody—only timid poems in the Collegian now and then.

ENA: Were they ahead of you? You took up writing later than they?

BNS: I was already writing, but I think I was not being published.

DGF: Were you trying? Were you submitting your work to editors?

BNS: No—because I was scared. I once wrote a story about how I happened to sit beside Eugenio Santos, who was the literary editor (of the Collegian). I could have submitted something to him, but I was afraid to ask. I was very timid, very shy, and very insecure. I was a very insecure boy from Tondo. UP was not known for having wealthy students, but even then I felt very much out of place because of my poverty. I don’t know—I was very shy then, and I still am. I was afraid. Fear of failure.

ENA: You did not, then, belong to a group?

BNS: No, I had no group.

ENA: But I have seen some of your writings in the Collegian.

BNS: Little by little, some were published. One of them sounded like “Hiawatha.” It was a poem called “Ruins,” I think very Hiawatha Terrible.

DGF: When did you really et published? After UP?

BNS: No, I was published even while in UP. Do you know how I really got published? It was this way. I wrote a story, and the title was “Fallen Angels.” The usual story famous in those days, a reversal story about virtue. Which turned out not to be virtue. It seems that’s bad—the fallen ideal, or something like that. Very corny. I know that now. It’s not a matter of whether it was a good story or a bad story, but it was the story that I wanted to write. I used to go to Graphic to submit my stories, and one of them finally was accepted by Litiatco. Litiatco was the one who discovered me, because he published my first story.

ENA: Do you remember how much you were paid?

BNS: Five pesos, I think. Because I remember that for my poems, I was paid as low as P2.50 by Philippine Magazine. A story of mine called “The Horseshoe” was based on the superstition that if you see a horseshoe facing you, that’s good luck. Because it got accepted. I had the courage to enroll in English 111, Creative Writing. In that class, S.P. Lopes, C.V. Pedroche, and the rest of us were made to submit stories. One day, Mrs. (Paz Marquez) Benitez said: “Who wrote this story, “The Years Are very Long?’” I said: “I did, ma’am.” “Will you read your story before the class?” Naku pinawisan ako! I was really very young, and very insecure. I had one school outfit—khaki, because it was used in ROTC. I had no other clothes. I was an orphan, you see. I was just living with my brother’s family. So I read my story. “What do you think?” she asked. All of them were critical. The most vocal was C.V. Pedroche. He said: “The situation is tragic, but the language is funny.” Someone else said, “It does not ring true; it is not believable.” I don’t know if they remember. But I remember because it was the turning point of my life as a writer. I thought: Wala na! I don’t know if it was Maria Kalaw who asked, “Mrs. Benitez, what do you think of it?” And she said: “Well, I think this is the best story I have ever read, written by a Filipino.” I was really . . . ang sarap! After class, she asked: “Will you allow me to submit this to A.V. Hartendorp of Philippine Magazine?” I said, “Certainly!”

ENA: What year was that?

BNS: I don’t remember. Perhaps the 30s. ’31 or ’32, perhaps. However, “The Horseshoe” came first, and was my first published story. The Graphic in those days listed titles on the cover. Every week I visited the news-stand to see if my story had been publi...

Table of contents

- Title page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- TWO WORDS AREN’T A PREFACE, A FOREWORD, OR AN INTRODUCTION

- INTRODUCTION

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- PAZ MARQUEZ BENITEZ

- CASIANO T. CALALANG

- LUIS G. DATO

- ANGELA MANALANG GLORIA

- LEON MA. GUERRERO

- MARIA KALAW KATIGBAK

- FERNANDO L. LEAÑO

- MARIA LUNA LOPEZ

- SALVADOR P. LOPEZ

- ARTURO B. ROTOR

- BIENVENIDO N. SANTOS

- LORETO PARAS SULIT

- JOSE GARCIA VILLA

- LEOPOLDO Y. YABES