eBook - ePub

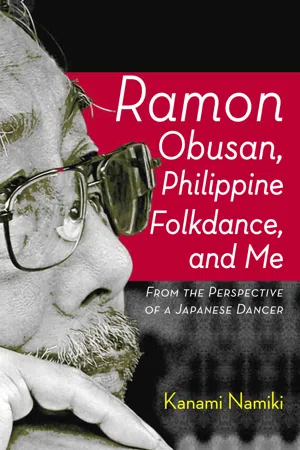

Ramon Obusan, Philippine Folkdance and Me

From the Perspective of a Japanese Dancer

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

"I know of no other work that succeeds beautifully in weaving together a history of the development of Filipino folk dance over the twentieth century, an outsider's insider's account of one of the top two folk dance companies in the Philippines, and a sensitive, wide-ranging reflection on how a 'foreign' (in this case, Japanese) dancer learns to become Filipino in bodily movement and sensibility."

— From the Foreword by Reynaldo C. Ileto

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Ramon Obusan, Philippine Folkdance and Me by Kanami Namiki in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Dance. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

DanceChapter 1

HAPONESANG MALANDI

WITH ARTIFICIAL SAMPAGUITA GARLANDS IN THEIR HANDS, GIRLS in long flowery and pastel-colored dresses walked slowly onto the stage to the smooth music of a Filipino string orchestra called rondalla. They entered alternately, from both sides of the stage. The last girl entered with a smile, but if one looked closely, one would see she was not wearing the sapatilya, low-heeled white slippers that she should have worn with her costume!

That girl was me in my first performance of Philippine folkdance in June 1995, at a dinner reception sponsored by the Philippine Embassy in Tokyo and the Tokyo office of the Philippine Department of Tourism, as a part of their tourism promotion. I was part of a group of Japanese students taught by a Filipino dance instructor to perform a medley of Philippine folkdances for this particular event. I was not prepared for the quick costume changes from one dance number to another, and I rushed onto the stage without putting on my sapatilya so I would not be late.

After the show, I was told by my Filipino instructor that I should not have entered the stage without my sapatilya, and I should have just caught up with the other dancers even if it meant entering the stage late. But how could I, immature as I was as a dancer then, think in such a flexible way? I am Japanese! I believe in being on time!

This was my first taste of culture shock as a Japanese dancer learning Filipino dance. Little did I know that there would be many, many more such moments in years to come, as I ended up devoting the next decade of my life to Philippine folkdance.

FIRST ENCOUNTERS WITH BAYANIHAN AND ROFG

I began my dance career in Philippine folkdance in 1995, as a founding member of the Philippine Cultural Dance Troupe of the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, which consisted of students and graduates of the Philippine Studies Program. From the outset, our dance troupe was artistically directed by former dancers of what was then known as the Bayanihan Philippine Folk Dance Company1 who worked in Japan, and occasionally performed with other Filipino dancers. Among them was a former dancer of the Ramon Obusan Folkloric Group who subsequently took over our dance troupe and brought us to the ROFG. So I became familiar with these two groups—“Bayanihan” and “Ramon Obusan”—but interestingly, my impressions of them were different, given the limited information we could get at that time.

We learned that Bayanihan was a professional national folkdance company of the Philippines that was internationally recognized, and whose members were drawn exclusively from children of well-to-do families. My impression then was that to become a dancer of Bayanihan, you must be good-looking and have a good complexion. Thus, to me, being in Bayanihan seemed prestigious and the dancers seemed to have some sort of social status. In fact, one of our first dance instructors was tall and good-looking although she was morena, or brown-skinned. But because she was morena, she danced the part of the princess in Singkil, a dance of the Maranao Muslim royalty and one of the most famous signature dances of the Philippine folkdance repertoire. This implied that she was a principal dancer or one of the star performers of the company, which I found very impressive.

However, frankly speaking, my impression of Bayanihan was not always positive. I was suspicious because some of our Bayanihan instructors in Japan were illegal immigrants, or TNT (from Tagalog Tago Ng Tago, meaning “always hiding”). I wondered why people from supposedly well-to-do families became illegal immigrants working in Japan and why the Philippine Embassy pretended not to notice the illegal status of their nationals and even asked them to teach Philippine dances to us Japanese dancers. From our perspective, illegal was simply bad. I was then an ignorant university student who did not understand the socio-economic situation in the Philippines where many Filipinos found work abroad to support their families in their home country.

In contrast to Bayanihan, the Ramon Obusan Folkloric Group was relatively less known. The people in the Philippine Studies community in Japan had little knowledge of the group. However, by chance, I had the good fortune to visit the headquarters of the group a year before. During our Christmas vacation in Manila in 1994, my friends and I were brought to the house of Ramon Obusan, which was also the headquarters of the ROFG.

We had no prior knowledge of who Ramon Obusan was, and what his group was about. As we entered the large Spanish-style antique house, I saw five or six dancers rehearsing in the open courtyard with Obusan, an old man who was moreno with white-and-grey hair and a mustache. A small tanned girl took a crouched position and slowly moved a black bull head, while male dancers fell in line facing the audience beating the ground with long bamboo poles that they held upright. It looked quite weird and creepy, totally different from what we knew as Philippine dance.

Ramon Obusan in Bagobo costume

When Obusan noticed us, he interrupted the rehearsal and made his dancers socialize with us. We were surprised that one of the dancers, a really good-looking guy, spoke fluent Japanese but in a strange way. He spoke like a woman! He told me that he had worked in Japan for years. However, I did not immediately realize that his job was that of an entertainer in a club (in short, he was gay and danced as a female). Altogether, I had a strange impression of the group. I could not comprehend what kind of dance group—and how good—it was.

We were given a great opportunity to meet both the Bayanihan and the ROFG folkdance companies in May 1997, when our dance troupe officially visited their headquarters in Manila. The dance studio of Bayanihan was then located in a commercial building near the Philippine Women’s University on Taft Avenue with which Bayanihan was affiliated. (Today, the company has its studio at the Cultural Center of the Philippines.) It was a typical dance studio surrounded by mirrors, but quite small. When we visited, we were greeted by young teenage dancers in uniform training wear—a white T-shirt and black sweat pants. This gave me the impression that they were very urbane, and they were indeed good-looking and had fair complexion. We observed their dancing in a rehearsal setting and I soon noticed that they consciously pulled up their bodies and stood tall, which to us, looked beautiful and professional.

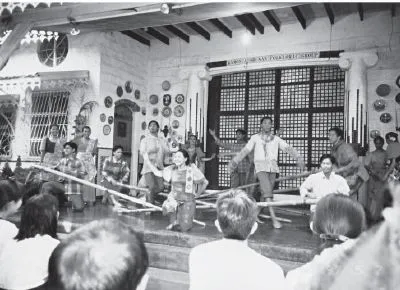

When we visited Obusan’s large, two-story ancestral mansion located in a residential area near the Manila International Airport in Pasay City, we were surprised to see all his dancers fully dressed in colorful costumes representing varied Philippine cultural and ethnic groups. There were so many of them! They guided us inside his museum-like house which was furnished with antique furniture and rare artifacts he had collected through the years. Various costumes were also on display. It was much better and more interesting than any museum in Manila. Benches were arranged in the courtyard where we sat when they gave us a casual folkdance performance. We were excited to see, for the first time, Philippine folkdance performed by professional Filipino dancers.

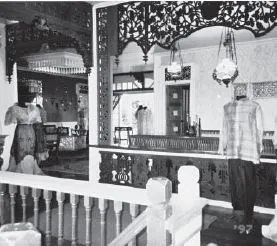

Obusan’s Spanish-style house in Pasay City

We noticed that, unlike Bayanihan dancers who looked beautiful and glamorous, Obusan’s dancers looked like “ordinary” Filipinos. There were mataba (fat), maitim (dark-skinned) and matanda (elderly) among them. We enjoyed their performance because some of the dance numbers were familiar to us.

But frankly, our initial reaction to their performance was rather negative. Their dance movements looked so natural but they seemed to have no dynamics. In short, in the eyes of Japanese students who were used to watching sophisticated and spectacular dance theater and had a preconceived image and idea of dance, they looked “ordinary.” One of my friends told me that I could do better than them.

However, I later realized that their natural and seemingly effortless, non-artificial movements actually resulted from continuous training and practice. I found out that it is, in fact, more difficult to execute dance movements simply and achieve this “ordinariness” or “naturalness” than to perform dynamically.

The first time I faced this difficulty was when we Japanese dancers practiced and polished our numbers at Obusan’s studio in Manila. In March 1998, the cultural dance troupe of TUFS came to Manila to perform several Philippine folkdances with the support of the ROFG. We had the last-minute practices at Obusan’s place before our performances. Obusan assigned some dance masters who took care of us in both rehearsals and actual performances. This was a great opportunity for us to learn correct and proper dance movements and execution from experienced dancers. But the rehearsal turned out to be tough as Obusan was so strict. It did not matter whether you were Japanese or Filipino; as long as you were under his tutelage, he did not hesitate to shout and fire rude words at you. We were so scared and tense in his presence, although we were not able to understand all the slang words he was using. Added to this, we had to rehearse outside in our bare feet, under the heat of the sun in the middle of the day. I remember that even when some of our dancers suffered from sunstroke, our rehearsal continued as if nothing had happened.

With Bayanihan dancers in their rehearsal studio (author in the back row, fourth from left), 1997

During the rehearsal, the dance masters told us that they could not touch or correct some of our dance numbers because “they are Bayanihan’s, and not ours.” That was when I realized that there were differences between them. Since our dance troupe initially had an instructor from Bayanihan, and later from the ROFG, our dance repertoire and performing style were actually halo-halo (a mix) of Bayanihan and ROFG versions. In fact, there are certain repertoires that Bayanihan performs but the ROFG does not. Even for the same dance number with the same name, each folkdance company performs it distinctively, to a greater or lesser extent, in terms of choreography, basic movements and performing style. But I only learned all this after I joined the ROFG in 2000.

Obusan’s dancers in various “ethnic” costumes, 1997

Inside Obusan’s house (second floor). The costumes displayed are various styles of westernized traditional clothing, 1997.

The stylized folkdances of Bayanihan are more familiar since they are based on balletic form. Hence, the distinctive or peculiar movements of each Filipino ethnic/cultural community, which are totally foreign to us, are blurred or reduced. Even the dances of indigenous and Muslim groups are performed in modern stylized form. For us Japanese dancers, it was relatively easy to learn the Bayanihan version since we shared the common concern for dancing beautifully, to pull up the body with a chin-up and to emote. In short, to show off on center stage. To be honest, this dance style actually made me feel good, graceful and beautiful as a dancer.

In contrast, the version of the ROFG is quite tough. The group is very conscious and meticulous about what they call “basics,” a core set of basic dance/body movements of different ethnic/cultural groups. The priority of Obusan’s dancers is to learn and execute these basics properly, so they made us master them. This method of making us repeat the basic steps over and over was a refreshing change from what I was accustomed to. Previously, learning Filipino dances meant memorizing the choreographic sequence of a whole dance, learning the steps and the formation so that you could dance, whether or not you could properly master and execute movements.

A casual performance given to TUFS group. The dance in the picture is Tinikling, 1997.

With Obusan, the first step was to learn and master the “basics,” the core movements used in a particular dance. Learning choreography and formation were secondary concerns. It was actually a boring and painstaking process, but I soon became very conscious about properly executing the basics. It was quite ann...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Abbreviations

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Haponesang Malandi

- Chapter 2 Philippine Folkdance and History Reconsidered

- Chapter 3 Ramon Obusan and His Folkloric Group

- Chapter 4 Close to the Original

- Chapter 5 The Legacy of Ramon Obusan, National Artist for Dance

- Appendices: Dance Repertoire

- Glossary of Ramon Obusan’s Dances

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Photo Credits

- About the Author