This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

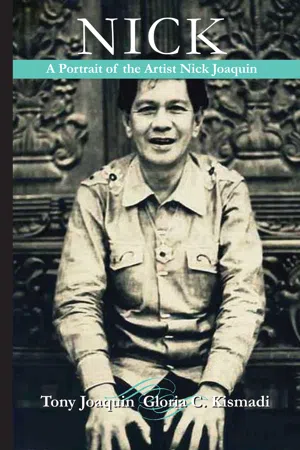

Years after his death, Nick Joaquin's legacy continues to live on.

Through his prolific writing—both fiction and non-fiction—this National Artist for Literature awardee has left his mark not only in the Philippine literary and journalistic community, but more importantly, in the hearts and minds of those who hold him dearest—his family and close friends.

With black-and-white photo folio.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Nick by Tony Joaquin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Journalist Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Journalist Biographies

It was one of those rare Sundays when Don Leocadio Joaquin could be at home with his family and he was truly enjoying it. He was already looking forward to the meal his wife, Doña Salome Marquez, was preparing. On weekends when her husband was home, she would prepare a special Sunday meal, a dinner complete with his favorite dishes, starting with appetizers and soup, all the way to fruit and dessert. In a way, it was an almost formal dinner and it was a must that all the children be there and the family sit down together. This was the way that Don Leocadio could catch up on what each of his children was doing.

The Joaquins were happy in their Paco home on Perdigon Street where they enjoyed the comforts and appointments of an upper middle class Manila family. Originally known as dilao because of the amarillo plants, yellow in color, that grew plentifully in the area, Paco was home to many well-known government officials and businessmen. Perhaps it was for this reason Don Leocadio chose to reside there so he could be with his friends and clients.

Rocking gently on his silyon, enjoying the cool, gentle breeze coming through the wide, open windows, he almost dozed off as he listened to his lovely daughter, Nene, playing one of her light classical pieces—at his request. The noises coming from the yard below, however, got him curious to see what his sons were doing. Looking out the window, he saw them engaged in a game of marbles, acting like young boys do—outshouting one another—in the hope that all the yelling and teasing would get the opponent to miss his target.

There were also the sounds coming from the kitchen, where his wife Doña Salome and her younger sister Etang were preparing the Sunday meal. He could hear his wife giving instructions and occasionally sharing some funny story that would make both sisters laugh. Curious, he walked over to the kitchen to find out and perhaps grab a savory or two in the process. He asked how much longer it would take before dinner would be served because he was thinking of taking a brief nap. Doña Salome saw him coming in and shooed him out, teasing him about the taboos on men coming into the kitchen before the food was ready. She also told him to stay awake since it would not be long before everyone would be called to sit down for the meal. It was bad luck to let food wait. Coming together for a meal as a family was a blessing from God and it was in respect for this that everyone had to be there before the meal began.

Feeling at a loss about what to do in the meantime, Don Leocadio decided to see what Onching was doing, knowing that if he didn’t, the boy would probably remain in the room which was Don Leocadio’s office cum library, engrossed in the book he happened to be reading, and miss lunch altogether. “Come, Onching, Mamá is about ready to serve the meal,” he said, putting his hand on the boy’s shoulder. Seeing Onching’s reluctance to put the book down, Don Leocadio asked him what he was reading. “Don Quixote, Papá,” the boy replied, barely lifting his eyes from the book.

Don Leocadio asked his son if the book was not too “adult” for him to understand. Cervantes was not an easy read and the boy was barely in his teens. Onching admitted that he really didn’t understand all of it, but he explained that he was quite drawn to the character of Don Quixote. And when his father asked him why, the boy replied that Quixote was his own person; he was different and unlike many heroes who always did what was expected of them. “He’s interesting. You never know what he’s going to do next.” The boy also commented on the way Cervantes described places and the way he put words together. Always obedient, however, especially since it was father who had come to get him, Onching reluctantly put the book down and followed Don Leocadio out the door. Nicomedes, or Onching, as the family called him, was the fifth of the ten children of Don Leocadio and Doña Salome Joaquin.

Leocadio Joaquin originally came from a prominent family of Tagalog lowlanders from Obando, Bulacan. He chose to go into law and was a brilliant student. When the insurrection began in 1896, he joined the fight under General Aguinaldo. An astute strategist, he rose in rank very quickly but was wounded in one of the battles. This ended his military career as a colonel. Upon the cessation of hostilities after the Philippines came under American rule, Leocadio set out to build his law practice and became very successful. General Emilio Aguinaldo, who was not only his commander but also a good friend, had predicted that when Leocadio was discharged, he would most likely become the best lawyer in the country. Leocadio immediately set out to prove just that and succeeded.

Don Leocadio specialized in handling land disputes. In the new government, laws on land ownership were starting to be established and problems were numerous. Families that worked their land from generation to generation suddenly found others claiming ownership over land that they had worked on for decades and believed rightly belonged to them. As regulations over land ownership became clear, all claims had to be registered and accompanied with proper documentation that would show legal ownership of the land. Most landowners had little or no documentation to show and they became easy prey to others who would go to any length to claim the land, even to the extent of falsifying documents and signatures. Don Leocadio’s sense of justice moved him to make it his priority to straighten such claims of land ownership. He had the reputation of being fair and honest, and was thus very much in demand, traveling as far as Tayabas and Surigao where he would often be asked to take on cases by families who felt they were being cheated out of land they believed was rightfully theirs.

In those unsettling times when traditional lands were being eyed by avaricious land grabbers, farmers and small landowners, who had always believed that the land they lived on and farmed was rightfully theirs, were suddenly being asked to provide certificates of ownership attesting that the land they lived off had belonged to their families for many generations. Many families suddenly found that their lands were being claimed and taken over by strangers who said they were distant relatives and belonged to the same family. While this may have been the case, they were willing, nevertheless, to risk family and personal relationships hoping to make more profitable ventures by selling the land to others who anticipated the expansion of towns and villages as increasing populations looked for additional residential areas or business venues.

The brilliant and kind Leocadio Joaquin had a reputation for integrity and honesty and he became known as a fair, just, and understanding lawyer. He showed patience while listening to the complaints of these landowners who found themselves at a loss when they realized they could lose their lands and find themselves without any means. Leocadio was an incisive analyst and an eloquent speaker. More importantly, his clients trusted him. He defended the exploited and won cases for traditional land owners who neither had the understanding about what was happening to their inheritance, much less the ability to speak up for their rights. For taking on their defense and winning back their lands, Don Leocadio was often paid handsomely and would return home with bags full of money. This was where most of his wealth came from. But there also were many occasions when clients could pay him only in kind and he would come home with a sack full of rice, or sweet potatoes, or a kaing full of oranges—whatever it was they could afford to give him—along with their loyalty. He accepted all of these graciously. Thus, as a procurador, he had established his reputation and was considered without equal.

In addition to his reputation of being a brilliant lawyer, he was attractive and gifted with a jovial and winning personality. Leocadio, thus, easily won the respect and friendship of all who met him, many of them being the most prominent and brightest young politicians in the provisional government being set up by the Americans. No less than Manuel Quezon was the godfather of his eldest son, Porfirio. Persuaded by friends, Leocadio made a half-hearted bid for a seat in the Philippine Assembly representing Laguna, but did not make it for he was often away, devoting his time to defending his clients instead of campaigning.

In one of his trips to San Pedro, Makati, fondly referred to as Sampiro by its residents, he visited the kamalig, a pottery factory, started by his father in the 19th Century and was attracted to a lovely young woman who lived in the area, Salome Marquez. At the age of sixteen, Salome was already a normal school graduate. She was teaching at the local public school when the family had to evacuate as a result of the American occupation. When the situation settled down, the family returned to the barrio only to discover that their home had been totally destroyed. A relative living in Binondo took them in until the new home in Sampiro was completely rebuilt.

By the time the family returned to Sampiro, the Americans had already opened a public school. Salome was appointed as a grade school teacher using Spanish as the medium of instruction. The Americans had already begun teaching English but with the number of students increasing, they set out to instruct the local teachers to take over some of the classes in English. Salome was bright and found creative ways to teach herself the new language and in so doing, drew the attention of the American instructors who, recognizing her abilities, assigned her to take a crash course in English which she mastered in less than six months. This enabled her to teach in English to her grade school students, and for this, her salary doubled. Barely eighteen, she suddenly found herself the sole breadwinner of the family, her father having become too weak to work. Seven years later, she met and married Leocadio Joaquin.

Cadio and Omeng, as they were affectionately called, had ten children. Porfirio, whom everyone called Ping, was the eldest. On the piano, Ping was brilliant and was already being hailed as one of the best classical pianists when he became sidetracked by the music that the Americans had brought with them and which everyone came to know as jazz. The Filipino musical purists disdained this new music and called it noise designed by the Devil himself. Ping, however, found it unusually creative, and would try and get hold of the latest sheet music for popular melodies whenever he could. Playing and listening to the music intently as he read the music sheets, he would, with his uncanny ability, shortly play a whole piece, reproducing it, and putting in improvisations of his own. Jazz allowed him the freedom to create his own sounds and rhythms that classical music did not and it soon became his passion, much to the disappointment of his mother who found it difficult to accept that her son would never give up the sound and beat of jazz once he and others like him discovered they were paid well at those times when they were asked to play, especially by the Americans.

Ping found friends who were of the same mind and who played different instruments, so together they formed a band. It did not take long before they caught the attention of nightclubs whose clientele were jazz-loving fans. At the same time, vaudeville shows that had also been brought over by American popular culture had started to become part of the Filipino entertainment world, and Ping and his band were hired to provide the accompaniment for those shows. Ping was so good at his music that eventually, he played, not only in Manila, but also traveled to cities all over Asia—Hong Kong, Shanghai, Surabaya—where jazz was enjoying so much popularity. Eventually, Ping Joaquin easily earned for himself the title “King of Jazz.”

Back in the sala, Don Leocadio looked down at the yard where he had earlier heard three of his sons arguing over whose turn it was to shoot the large marble that would hopefully push most of the other smaller ones out of the boundary they had drawn on the ground. Don Leocadio smiled as he watched them and called them to wash up and get ready for lunch. Having been raised to be always obedient, especially when it was their parents telling them what to do, they stopped their game, with Gusty reminding the other two that it would be his turn to shoot when the game resumed.

When the family was ready, each standing behind his own chair around the large dinner table, Doña Salome came out of the kitchen followed closely by the assistant cook bearing the main dish prepared for the Sunday meal. Behind them came Tia Etang, Doña Salome’s younger sister, bringing in a huge tray filled with more food. Onching’s eyes grew larger, when he saw all that was placed on the table. He loved good food and his mother was an excellent cook. “Ah, pochero,” he exclaimed. “Gracias, Mamá,” It was indeed, one of his favorites.

Seeing that two places were still empty, Don Leocadio’s thick eyebrows went up as he looked at his wife. Just at that moment, Enrique burst in, having come from somewhere in the neighborhood where he happened to be hanging out with his friends. One of the maids had quickly gone after him, sent by Doña Salome, knowing how strict Don Leocadio was about the family being at their places before the meal started. Meals were blessings, he always said, and he insisted on the entire family being all in place, quiet, and ready to start the prayer.

Don Leocadio glared at Enrique while everyone stood in silence, knowing they would all have to wait as Doña Salome signaled to Enrique to wash up first. Noticing Don Leocadio looking at the other empty seat, Doña Salome quickly explained, “Porfirio no se puede venir porque esta occupado ensayando con los musiqueros.” Don Leocadio shrugged his shoulders, accepting, although not quite understanding, his eldest son’s interest in the new kind of music that was beginning to get popular all over the city. Jazz had come and its aficionados were convinced it was here to stay. Don Leocadio then motioned to Doña Salome to start the prayer. While Don Leocadio made the sign of the cross and sat mute at the head of the table, Doña Salome led the family, praying in Spanish. This done, she began to ladle the soup, the first helping always for the padre de familia.

Of the ten children of Don Leocadio and Doña Salome, two never lived long. Coming after Ping, Leocadio Jr., whom the family called Totong, was accident prone even as a young boy. One time a burning lamp fell on his body, and once, he was run over by a carromata. At another time, he was electrocuted accidentally. Luckily, Ping had the presence of mind to grab him and put him under a very cold shower until he regained consciousness. Totong survived all these mishaps but unfortunately, he died young, not from another accident, but because of a burst appendix.

The other child was stillborn. Her parents, disappointed at losing a child that would have been their second daughter, had her buried immediately and no one today even remembers whether she was given a name.

Coming after Totong was the girl that Don Leocadio and Doña Omeng had been wanting and waiting for so long. Generosa, known as Nene to the family, was everything the couple had hoped for in a girl. Lithe, lovely, and lively, Nene had a very pleasant disposition and what made her father happiest was the way she seemed to have inherited his sense of humor. At times, they would laugh over something one of them had said, even when no one else in the room understood it. It was something only the two of them would find humorous and for Don Leocadio to be able to share it with his daughter made Nene very special to him. Nene also loved playing the piano, but perhaps, overwhelmed by Ping’s talent, she never went beyond the light classics that she played especially for her father.

Fifth in the line up of Joaquin offspring was Nicomedes, Onching to the family. He was born on May 4, 1917, in their residence in Paco with Doña Salome being ably assisted by a skillful comadrona. At that time, it was still common practice to have a midwife come, rather than rushing the expectant mother off to the hospital.

From the start, Onching was a loner. Quiet, sensitive, to the point of being reclusive at times, he rarely joined his brothers at playing games and instead spent most of his time in his father’s library, his head buried in a book. Doña Salome, being the teacher she once was, and noticing how books attracted the young boy, taught Onching to read at a very early age in both Spanish and English. He was curious about everything, and nothing ever escaped his notice. In addition, he had a prodigious memory for people, places, events and other happenings although once in a while, he would pretend he knew nothing if he was not in the mood for talking about it. His love for Spanish and his fluency in English came from his mother whom he relentlessly asked to get him books, continually pressing her for words and meanings in both languages. His curiosity was endless and he always remembered all that he read.

Four more boys came after Onching: Walfrido, whom the family called Freddy; Enrique, who, as a child was known as Titong, but who later preferred to be called Ike; Agusto whom everyone called Gusty, and Adolfo. Freddy was the soft-spoken one. He was kind, respectful, and polite to everyone, even to cocheros and street sweepers. He loved to write and might have given Onching a run for his money later on in life, but Freddy never had that opportunity. As part of the requirement for all Filipino males, all students from both public and private schools had to undergo two months of cadre training. During this time, they were brought to a camp far from the city to train on all aspects of military methods and fighting techniques. Freddy was assigned to train in Tagaytay and was made to carry out hospital duty when World War II broke out on December 8, 1941. The hospital in Tagaytay was among the military objectives that were bombed and strafed by Japanese dive-bombers. It took a direct hit and Freddy was thought to be one of the casualties although there were some who pointed out that he was one of the young soldiers who were sent to Bataan on the Death March.

Titong, or Ike, was the son who inherited his father’s savoir faire. Bright, clever, and street smart, he was the most outgoing of the brothers. People were attracted to him because of his looks, his exuberance, his zest for living, his guileless personality, and his sharp wit. It is thus no surprise that Gusty, coming after Ike, grew up completely in his shadow. Gusty was shy and self-conscious and tried to imitate his older brother but without success, so much so that he had convinced himself he was the ugliest of all the brothers and his personality the most colorless. At parties, as soon as Ike entered the room, all the young people would make a beeline for him. Gusty, realizing that nothing like that would ever happen to him, never went inside a room together with Titong. He knew from experience that he would only be ignored. So, Gusty would wait until his brother was already in another part of the room, holding everyone’s attention, before he would quietly enter and find the darkest corner. Yet Gusty also had his own talents. He could sing, dance, and perform. He would make his own plays and act out all the roles, changing his voice to suit the character he played … but this he did only at home for the family. Gusty’s greatest talent was drawing. Give Gusty a sketchbook, a pen, and some ink, and he would make drawings of anyone who asked. Unfortunately, he could ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter I

- Chapter II

- Chapter III

- Chapter IV

- Chapter V

- Chapter VI

- Chapter VII

- Chapter VIII

- Chapter IX

- Chapter X

- Chapter XI

- Works

- Awards

- The Artist

- The Authors