This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book is a sequel to Cine: Spanish Influences on Early Cinema in the Philippines, and part of Nick Deocampo's extensive research on Philippine cinema. Tracing the beginnings of motion pictures from its Spanish roots, this book advances Deocampo's scholarly study of cinema's evolution in the hands of Americans.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Film by Nick Deocampo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas & Historia y crítica cinematográficas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Cinema and Colonization

Chapter I treads the twin paths of cinema and colonization. It provides a necessary beginning to the book, exploring ways that the Philippines figured in early American cinema in the age of renewed Western colonial expansionism. Spreading its territory overseas with the coming of the 20th century, the United States of America found itself embroiled in a war with the Spaniards, first ignited in Cuba but later ending up in the Far East after a naval fleet was sent to las islas Filipinas. Under the guise of helping native Filipinos overcome centuries of Spanish colonization, the true intention of the Americans in keeping las islas Filipinas to serve as a Pacific outpost for U.S. interests in Asia deeply frustrated native revolutionaries in their dream to attain independence for their country. Facing the power of a new conquering force, the Filipinos’ fight against the Americans proved more bloody and vicious than their long, drawn-out struggle against the Spaniards. Against the backdrop of war and revolution came several claims—some unproven while others were outright lies—about some film footage taken at the battle of Manila Bay. While many of the claims are hard to prove, subsequent filmic representations of the Philippines and its natives began to surface in both reenacted newsreels as well as those shot on actual location from 1899 to 1902 and which survive to this day.

The earliest accounts of films made about the Philippines showed an international mix of filmmakers, including a British duo working in New York and one of the world’s film pioneers in France. The studio of inventor Thomas Alva Edison produced “reconstructed newsreels” as early as 1899, providing Filipinos their cinematic debut in films that were among the world’s earliest-made. But while Filipino soldiers were killed by American infantrymen in battlefields, they were denied actual screen presence, no matter if African-Americans stood in for them, thereby reinforcing the fictional swaddling of the early film productions.

On the other side of this filmic representation were films actually taken in the Philippines by two pioneering American cameramen. The first on record to shoot films in the Philippines was the travel lecturer Elias Burton Holmes, who made travelogues and “sham” footage for use in his lecture presentations in America’s high-class entertainment circles. The other was C. Fred Ackerman, sent by Edison’s rival, the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company (AM&B), to be embedded in the U.S. Army, which saw battle in the far-flung territory. His actual footage was among the first to show America’s newfound possession on screen and the battles its soldiers were engaged in (not mock-up scenes). Ackerman’s extant films, photographs and the articles1 he wrote about the Philippine war provided incisive views of the military campaign as entry point for American cinema and of war as the first subject in the depiction of the prospective colony.

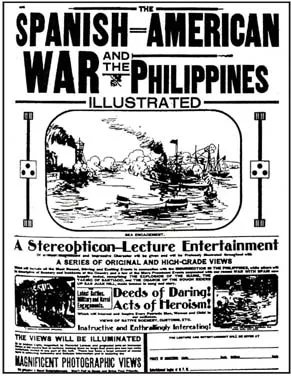

Movie ad heralds U.S. triumph in the Spanish-American War.

The coming of the Americans to the Philippine Islands helped stimulate the nascent growth of motion pictures. Introduced in 1897 by a Spanish businessman, Francisco Pertierra, and a Spanish soldier, Antonio Ramos, film became a novelty entertainment, confined during its incipient days among the elite class in the country’s capital, Manila, but also with reported showings in the southern cities of Ilong-Ilong (now Iloilo) and Sugbu (Cebu).2 The early growth of cinema followed the shift in the country’s political administration, and spurred a change in cultural identity that would commence from the use of the medium. Despite the subsequent American domination in the Philippine Islands, Hispanic influences remained pervasive among natives—not the least in the area of emergent film culture. The tug-of-war between two hegemonic cultures—Hispanismo and Anglo-Sajonismo—led to a unique growth of motion pictures that in subsequent years would point to the emergence of a native cinema.

Starting with this chapter, the period of early cinema commences. As mentioned in the Introduction, this is a special moment in the history of cinema as it was during this time when the motion picture was introduced and its growth was marked by a dependence on Europe rather than Hollywood. Discussed ahead will be traits that would mark this period as one where films were short, silent (although accompanied by live music or lecture), in black and white (but which could be colorized), and were initially in one-shot scenes lasting for about a minute and containing visual presentations that served as “attractions,” such as exotic locales or scenes of war like those found in Edison’s films.

The Spanish-American War

On May 1, 1898, the course of world history changed. The Spanish-American War that earlier erupted between two Western powers—Spain (an old-time maritime power) and the United States of America (asserting its extra-territorial claims)—was marked by a naval battle for control over Spain’s colony in the Pacific. The triumph of the U.S. naval fleet over the reputedly invincible Spanish armada at the battle of Manila Bay surprised the American public at the suddenness and ease of their triumph. Their victory signaled America’s ascent as the new world power. Its triumph in the Pacific climaxed a war that was ignited by the bombing on February 15 that same year of the battleship Maine, an American warship docked at Havana Bay in Cuba. The Americans suspected the Spaniards of destroying the ship. As events heated up, with the American “yellow press” fanning public sentiments to cry for revenge, an ambitious ranking officer of the U.S. Navy, Assistant Secretary Theodore Roosevelt, hatched up plans to invade other colonies under Spain’s possession. As early as February 25, a confidential dispatch was sent by Secretary Roosevelt to Commodore (later becoming Admiral) George Dewey, ordering him to undertake a mission to take the Philippines in the faraway Pacific.3 The dispatch reads:

“Order the squadron, except Monocacy, to Hong Kong. Keep full of coal. In the event of the declaration of war with Spain your duty will be to see that the Spanish squadron does not leave the Asiatic coast, and then offensive operations in Philippine Islands. Keep Olympia until further orders.”4 (Italics supplied)

Battle of Manila Bay

Roosevelt’s dispatch anticipated the war that was to come. It was the first among several dispatches issued by the U.S. government ordering Dewey, as Commander of the Asiatic Squadron, to engage in combat the Spanish fleet guarding Spain’s Pacific colony. While President William McKinley controlled the passion of the American public to exact revenge for their soldiers killed in the Havana incident, the U.S. Navy had Dewey’s fleet equipped with coal, ammunition and supplies. With war a foregone conclusion, Dewey sailed east, anticipating his orders to do battle. His Pacific fleet anchored in Hong Kong, awaiting instructions from Washington, D.C. When war was finally declared on April 25,5 “telegraphic orders to capture or destroy the formidable Spanish fleet then assembled in Manila were sent to Commodore Dewey.”6

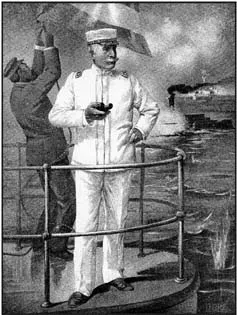

U.S. cruiser Olympia was Commodor Dewey’s main battleship during his naval charge at Manila Bay.

Commodore George Dewey led the triumphant American assault against the Spanish forces in the Battle of Manila Bay.

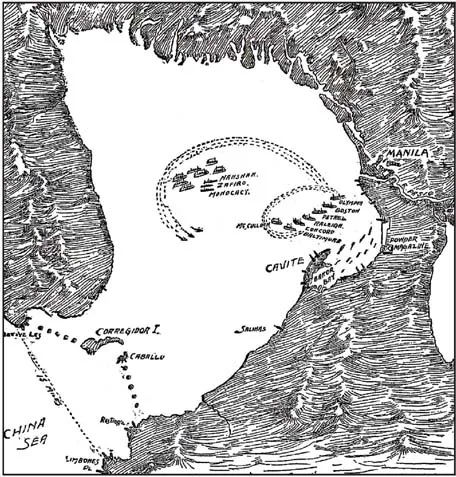

One such order came from Mr. John D. Long, Secretary of the Navy, commanding Dewey to “Destroy or capture the Spanish fleet.” Hardly had the orders reached Dewey when Great Britain issued a proclamation of neutrality, forcing Dewey to steer his ship away from Hong Kong, a British colony, to Mirs Bay, a Chinese port. Once the order for war reached Dewey, his fleet left the Chinese port of Mirs on Wednesday, April 27, aboard his flagship Olympia, in a convoy of eight other warships and boats that formed an impressive war flotilla. The U.S. fleet consisted of the Olympia (Dewey’s flagship), Boston, Raleigh, Baltimore, Concord, Petrel, McCulloch (a dispatch boat), and the transport boats carrying coal for the fleet, Nanshan and Zafiro. They were on their way to war against Spanish forces in the Philippines.

On a moonlit night on April 30, Dewey sighted Corregidor, a small island guarding the entrance to Manila Bay. It was only a matter of time for the battle to commence. In his letter to the War Department in Washington, Dewey recalls his entry to Manila Bay and the subsequent battle that ensued:

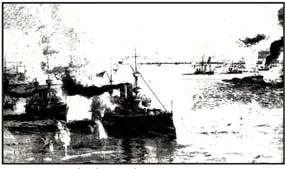

The Manila harbor was the scene of Comm. Dewey’s naval maneuvers.

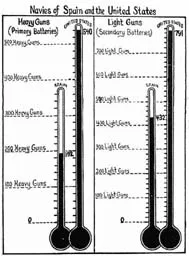

A comparison of U.S. and Spanish war capabilities

Comm. George Dewey’s battleship Olympia leading tha assault against the Spanish armada in this artist’s sketch of the Battle of Manila Bay.

Flagship Olympia, Cavite, May 4, 1898.The squadron left Mirs Bay on April 27. Arrived off Bolinao on the morning of April 30, and, finding no vessels there, proceeded down the coast and arrived off the entrance to Manila Bay on the same afternoon. The Boston and Concord were sent to reconnoiter Port Subig (sic Subic). A thorough search ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- What They Say About The Book

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Colonial Beginnings of Native Cinema

- Chapter I: Cinema and Colonization

- Chapter II: Pioneer American Filmmakers

- Chapter III: Films about the Colony

- Chapter IV: Pre-Hollywood Manila

- Chapter V: A Nascent Film Industry

- Chapter VI: Early American Film Productions

- Chapter VII: Roots of Hollywood Dominance

- Chapter VIII: Hollywood's Rupture and Return

- Chapter IX: Destination: Hollywood

- Chapter X: Hollywood Influences on Technology and Economy

- Chapter XI: Hollywood Influences on Material Production and Aesthetics: Studio System, Film Genre, Star System

- Chapter XII: Hollywood Influences on Language and Ideology

- Afterword

- Bibliography