![]()

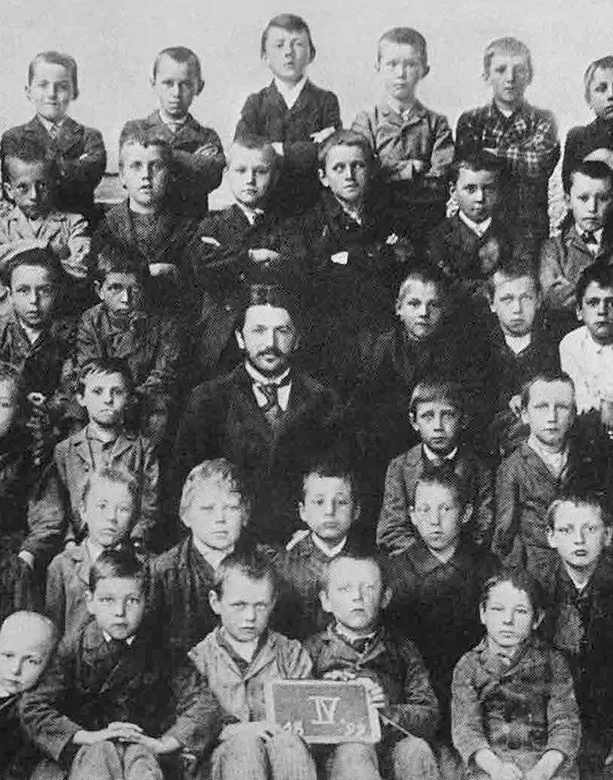

The class of 1899 – Adolf Hitler at primary school in Leonding, Austria. Hitler stands tall in the backrow, centre. He did not do particularly well in school, and left formal education in 1905.

CHAPTER 1

CHILDHOOD

To suggest that Hitler’s origins and early life were ‘mysterious’ would be unnecessarily melodramatic: but they were undoubtedly obscure; and important details remain unclear. Most elusive of all, however, is any sense – despite real and evident hardships and humiliations – of convincing explanations for the evil he’d eventually unleash.

Hitler’s history was being assiduously rewritten even before it had properly begun. The process seems to have started with his father. In 1876, when he was pushing 40, although still without a son, Alois Schicklgruber took formal steps to change his name. A customs inspector in the little town of Braunau am Inn, in Upper Austria, he was from this time on known as Alois Hitler. He also had a ‘legitimate’ birth bestowed upon him retrospectively by a parish priest; hitherto he had been down as ‘paternity unknown’.

DOUBTFUL PARENTAGE

Alois did not pluck his now-notorious surname out of nowhere. One Johann Georg Hiedler (1792– 1857) had played a major part in his upbringing, having married Alois’s mother, Maria Anna Schicklgruber, in 1842. Even so, it is not certain that this Johann Georg had been the boy’s biological father: by the time they wed, Alois was five years old. Nor is that missing half-decade the only period of Maria Anna’s life left unaccounted for: much remains mysterious about the months – even the years – before her baby’s birth.

Forty-two years old and a domestic servant in the village of Döllerheim, in Lower Austria, Maria Anna Schicklgruber was not obviously a ‘person of interest’ from a historical point of view. Poor and uneducated, a menial toiler and a resident hanger-on in other people’s households, she had no appreciable social status of her own. If she is a subject of scholarly investigation now, it is because of a grandson she never saw, and who wasn’t born till more than 40 years after she had died.

Maria Anna was born in Strones, a little village in Waldviertel, Lower Austria, northwest of Vienna. Her father had been a peasant-farmer there. Thereafter, we more or less lose track of Maria Anna until, on 7 June 1837, the birth of her son Alois is entered in the Döllerheim parish register. How long she had been living there prior to the birth remains unknown, as do her whereabouts before coming to the village.

REALLY A ROTHSCHILD?

In the absence of more evidence, the scope for speculation is limitless: Maria Anna’s biography becomes a blank slate for scholarly speculation at its wildest. It is notoriously difficult to prove a negative. And who would want to, when it’s so gratifying to our sense of historical schadenfreude to claim that the man responsible for the Holocaust was in some sense ‘really’ Jewish?

As early as the 1920s, there were rumours in Germany that Hitler’s grandmother had, at the time of Alois’s conception, been working in the Vienna household of Salomon Mayer von Rothschild, head of the Austrian branch of the famous banking dynasty. Eagerly as the story was retold, however, most acknowledged its unlikeliness even then: there’s no supporting evidence for the claim.

THE FRANKENBERGER FACTOR

Then there is the appeal of the less outrageous argument that Hitler’s father may have been a member of the Frankenberger (or Frankenreiter) family. In 1946, the Third Reich’s former Minister of Justice, Hans Frank, revealed (drawing, he said, on evidence from Adolf’s nephew Alphonse Hitler), that Alois’s mother had worked as a cook in this bourgeois household in Graz, an important commercial city south of Vienna.

Family members had stayed in touch with Maria Anna for many years after she had left their service, even paying maintenance for her child. The conclusion some people drew is that the family cook must also have done service – whether willingly or reluctantly – as the lover of one of the family’s men; most likely, Frank suggested, of the Frankenbergers’ 19-year-old son.

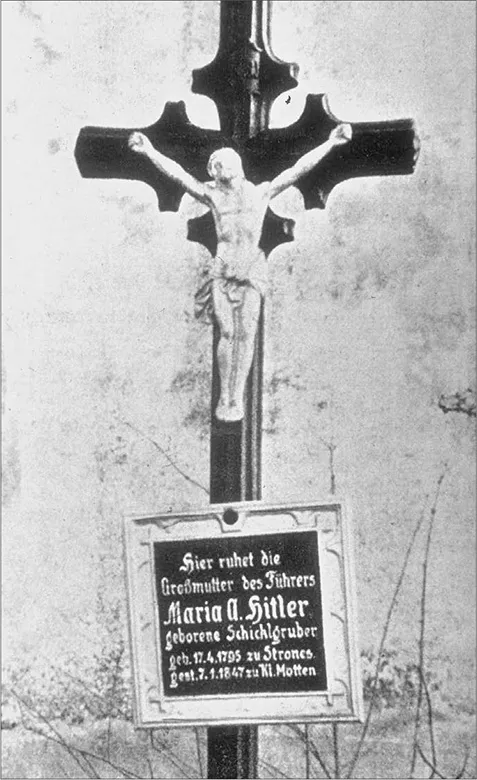

Rural poverty in the nineteenth century was far from picturesque. Maria Anna Schicklgruber was born here, at Strones in Lower Austria.

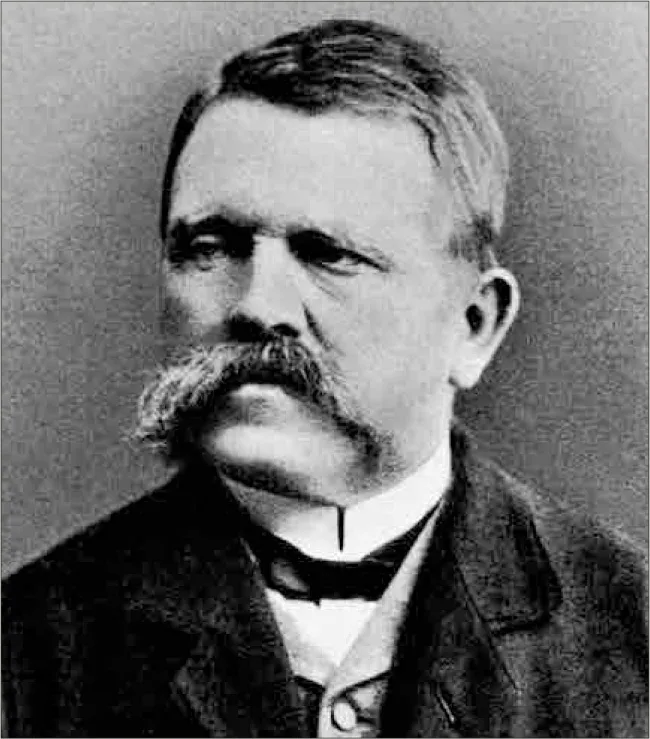

Salomon Rothschild (1774–1855) extended the famous family’s banking business into Austria. And, according to a later rumour, fathered Alois Hitler.

A sensational and opportunistic revelation, made in the context of Hans Frank’s memoirs (written soon before his execution, and appropriately entitled At the Gallows’ Foot), this story started to seem much more plausible when Franz Jetzinger revived it in the 1950s. The author of Hitler’s Youth (1956), Jetzinger was no war criminal scrabbling to find favour with his captors, but a priest, a social democratic statesman, a civil servant and sometime librarian of Linz. It’s scarcely surprising that this study should have caused a stir.

However, notwithstanding his clerical status, academic reputation, political respectability and general integrity, Jetzinger’s claims couldn’t stand up. No record has been found of any Jewish family named Frankenberger or Frankenreiter living in Graz during the 1830s. (Nor was it likely: throughout this period, Jews were prohibited from living in that part of Austria. Hitler’s Nuremberg Laws were only to be the latest in a very long line.) As seems to happen so often where the life and times of Adolf Hitler are concerned, what seems the most solid and authoritative of scholarly sources turns out to owe more to emotion than to fact.

SECRETS AND LIES

Maria Anna herself was to be no help to the historians of the future. For whatever reason, she would not reveal the identity of her baby’s father, and Alois went down in the baptismal register as illegitimate. The obvious candidate for his paternity would seem to be Johann Georg Hiedler. However, this obviousness introduces additional doubt: if Johann Georg was Alois’s father, and if he was to marry the boy’s mother a few years later, why did he not marry her at the time?

The mundane truth may be that it wasn’t deemed to matter much and that no enormous urgency was felt. Legitimacy was important, certainly, but its significance lay mainly in the fact that those born out of wedlock were not allowed to inherit property. Ultimately, it would matter a great deal to Alois, but as long as Johann Georg remained alive and in a position to save and spend his own money and dispose of his own property himself it very likely didn’t signify much either way.

There may, moreover, be less to these archival shenanigans than meets the eye. There’s a striking casualness about the way the parish priest in Döllerheim went about his work. A crude crossing out removed Alois’s ‘out of wedlock’ status; the quickest of scribbles substituted ‘within wedlock’. It’s true that the writer signs his name (introducing the intriguing question of just how legally binding this ‘legitimization’ could really be), but it can hardly be claimed that he went to elaborate lengths to cover his tracks.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Another possibility is that Alois’s uncle – Johann Georg’s brother, Johann Nepomuk Hiedler (1807–8), who had no sons himself, and faced with the prospect of his family’s surname disappearing – had demanded the change as the price of his dying legacy. That would offer another explanation of the late switch from Schicklgruber to Hitler. It also raises the question of why Alois didn’t adopt Johann Nepomuk’s favoured form of ‘Hiedler’, or the other versions he was known to use: ‘Hüttler’ or ‘Huettler’. There is no contradiction, necessarily, between Alois’s uncle’s pride in his surname and his easy-going attitude to its spelling. Even so, it wraps what was already an enigma in another layer of mystery.

Catholic piety marked Maria Anna’s grave, as it appears to have imprinted her entire life. Her grandson would despise such simple faith.

A further question could be posed: could Alois’s ‘uncle’ have been his father all along? That leaves Johann Georg as nothing more than his brother’s obliging or unwitting stand-in as Alois’s parent, with Johann Nepomuk merely making him his legal heir when the time came. The truth is we don’t know: there is no more evidence that Johann Nepomuk was Alois’s father than that Baron Rothschild was – and there is no firm evidence that Johann Georg was, either.

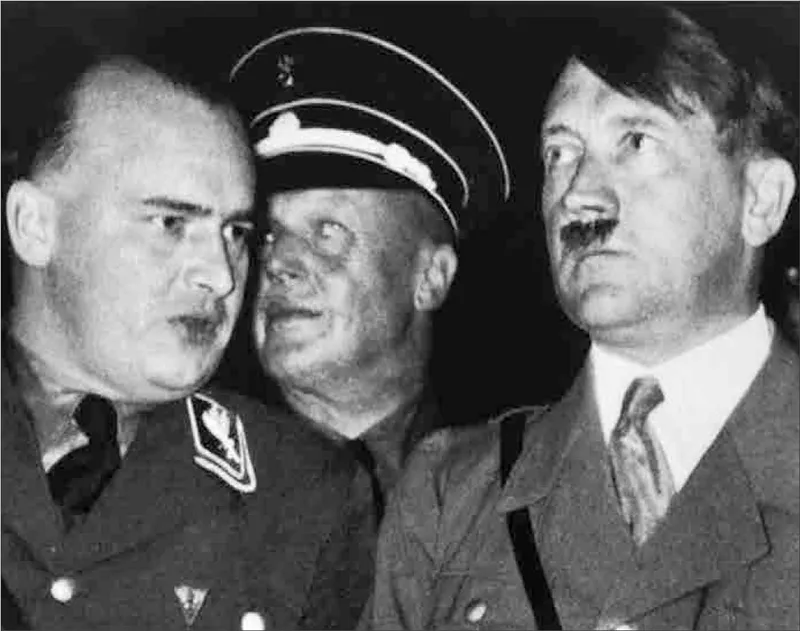

Hans Frank (front left) served Hitler loyally as Justice Minister, but his post-war memoir served up little more than smears.

A storm of confusion, secrecy and ignorance had formed round Adolf Hitler’s antecedents even before he had been born. That confusion is only compounded by our inability to truly understand the moral and social values of the time. Nineteenth-century Austria was unabashed about things we might have expected it to be more secretive about and yet a lot more exercised about issues that would not have worried us. If any of this is of more than academic importance, it may be because a sense of the dubiousness of his origins may have communicated itself to young Adolf, making him more determined to forge and fulfil a destiny of his own.

LIKE FATHER…?

Whatever the doubts about his parentage, Alois’s personal resolve was indisputable. He left school at 13, to be apprenticed to a cobbler, but he doesn’t seem to have settled for this. Five years later, in 1855, availing himself of a government scheme that set out to recruit and train officials from the Empire’s more far-flung corners, Alois was received into the imperial civil service. That he pursued this goal shows drive and determination, as did his slow and steady rise through the ranks of the bureaucracy.

But was this career to be a source of resentment, too? Alois was by no means unsuccessful. In 1892, he reached the rank of Higher Collector of Customs – the highest position open to an officia...