![]() Part One:

Part One:

Gendering later life work: empirical, theoretical and policy issues![]()

ONE

The empirical landscape of extended working lives

Debra Street

Introduction

Populations everywhere are ageing, but especially so in affluent countries. People are living longer and reaching older ages healthier and less frail than at any other time in human history. The combination of unprecedented longevity and the growing size of aged populations makes it obvious that state pension systems have become expensive components of modern welfare states. In most countries, politicians and policymakers are pursuing neoliberal policies to limit state interventions into social welfare in general, and to minimise, where possible, the growth of pension costs in particular. These complex social, economic and political circumstances are all part of the empirical landscape of extended working lives.

The sheer magnitude of demographic change seems, unavoidably, to pose some challenges for traditional public defined contribution pension systems, which are typically the costliest social policy tranche in most affluent countries. Although productivity increases since the mid-20th century created the capacity for nations to first expand, and then sustain, their welfare states, the changing ratio between young and older citizens undeniably puts the issue of the responsiveness of pension systems into public discourse. Alongside the policy influences associated with population ageing, current political preferences for welfare state restructuring (Pierson, 2001; Gilbert, 2002), the re-individualisation of risk (O’Rand, 2011) and neoliberal ideologies (Hacker, 2006) work together to create a seemingly irrefutable logic: people must extend their working lives and delay retirement. From a public policy perspective, the argument is often that individuals must wait longer to retire because their fellow citizens cannot contribute enough revenue to keep public pension promises. From a neoliberal ideological perspective, the state should stop nannying individuals by offering traditional pensions. Instead, individuals should be able to choose pension arrangements that they prefer and be more responsible for financing their own retirements, a process of re-individualising risk (see O’Rand, 2011). From a human capital perspective, and particularly in the context of proportionately smaller working-aged populations, another claim is that older workers have scarce human capital that employers need, and that failing to use older workers would be both irrational and inefficient (Weller, 2007). Furthermore, if the popular culture pundits have it right that ‘70 is the new 50’ (Byham, 2007), individuals themselves may not only want to extend their working lives, but also benefit from it beyond earning wages (see, eg, the vast and growing literature on ‘successful’ ageing and its productive/active variants). Macro-level circumstances (demographic change, policy actions and ideological stances) combined with meso-level processes (evolving labour markets, firms coping with a projected shortages of workers) and claims that individuals want to work to older ages make initiatives designed to encourage workers to delay retirement and extend working lives widespread and seemingly inevitable.

This chapter sets the stage and complicates the seemingly simple facts that provide the overarching rationale for extending working lives everywhere by presenting the empirical patterns of real-world experiences for current older workers in the countries (Australia, Germany, Ireland, Portugal, Sweden, the UK and the US) analysed in greater detail in this book. Consequently, this chapter presents population-level data for each country (where available) to document the characteristics of populations, older workers and national labour markets. The empirical landscape presented here also provides a foundation on which the chapter authors build. For the facts to be fully considered, Krekula and Vickerstaff argue convincingly (in Chapter Two) that understanding requires problematising the life courses of both older people and ageing workers. This stance is amplified in Chapter Three, where Ní Léime and Loretto turn a feminist political-economy lens that is sensitive to life-course issues on policies associated with extended working lives. Becoming acquainted with the empirical landscapes of these countries can also help readers better understand similarities and differences experienced internationally, challenging the simplistic idea that extended working life could ever be a straightforward enterprise or a one-size-fits-all solution that would work everywhere. Populations are ageing. Pension systems are under pressure. However, exhorting individuals to stay in work to later ages or merely shifting retirement ages upwards, in the absence of thoughtful policies and practices that make work pay for older workers and their families, will accomplish little more than consigning a large subset of precariously employed older workers to low-wage, low-quality employment (Lain, 2012) and redistributing an even heavier burden of risk to some of the most vulnerable older citizens in each country (Ní Léime and Street, 2016). Understanding the foundation for the ‘must work longer’ claim starts with considering some of the empirical realities of ageing populations and older workers early in the 21st century.

Simple problems, simple solutions?

Must all or most workers in affluent countries remain in employment to older ages? A widespread conviction seems to be ‘yes’, and that the challenges of ageing populations and expensive pensions systems can be met by that straightforward and inevitable solution. Future workers must simply work longer than workers currently do (see Vickerstaff, 2010). The assumption is that individuals will be willing and able to remain in employment and take some pressure off state pension systems by doing so. As straightforward as that seems, such a simplified stance masks an incredibly complex set of multi-level interactions within country-specific labour markets, and a stunning lack of awareness of the interconnectedness of global trends, national economies, social policies and family lives. Even if extending work is a feasible strategy for some workers, making it a successful strategy for most workers can only be effective if policy changes are managed carefully and include initiatives that can support the many older workers whose risks and vulnerabilities are already well documented and understood. The first complicating factor is that national labour markets operate in a globalised economy: jobs are not available on demand (Brady et al, 2005). Further, labour markets are comprised of structured inequalities: classed and gendered workers and inadequate and unevenly distributed employment opportunities. The second complexity involves normative expectations that employed women are still held most responsible for unpaid care work (Ginn et al, 2001; Bianchi and Wight, 2010; Bianchi, 2011). Exacerbating that issue is the rapid change in the private sphere of family forms and intimate social relations (Bianchi, 2011). The third complexity is the reality of stagnant wages (Saez and Zucman, 2016) and the inability of many workers to save for their own retirements (Helman et al, 2015), even while currently employed. Expecting public pension system respite in such circumstances is a bleak prospect. A fourth complicating factor is in the jobs sector itself, populated as it is with reluctant employers (Johnson, 2007; Roscigno et al, 2007) or, in many places, few to no appropriate available jobs for older workers at all. There are many more. However, each of these complications is nested, for each country, within the additional complexities of national economies and cultures.

Other underlying assumptions to the uncritical advocacy of extending working lives are equally problematic: that older workers choose to retire, rather than face unemployment, underemployment or redundancy; that older workers can easily remain employed or find appropriate alternative employment when jobs are lost; that older workers’ health and level of physical function are sufficient for the jobs that are available; that workers’ non-age-related characteristics will be no impediment to employment; and that older workers’ jobs will be good enough, that is, appropriate to their training, skills and abilities and offering enough hours and pay to promote financial security as working lives are extended in tandem with retirement age increases. Downplayed in such exhortations are many of the disconnects associated with: the spatial realities of skill-matching in an increasingly globalised labour market; predictable differences in the health statuses and functional capacities of some older workers; the persisting gender gaps in pay and normative expectations for unpaid work; and the pervasive ageism that contributes to the reluctance of many employers to retain, retrain and/or hire older workers.

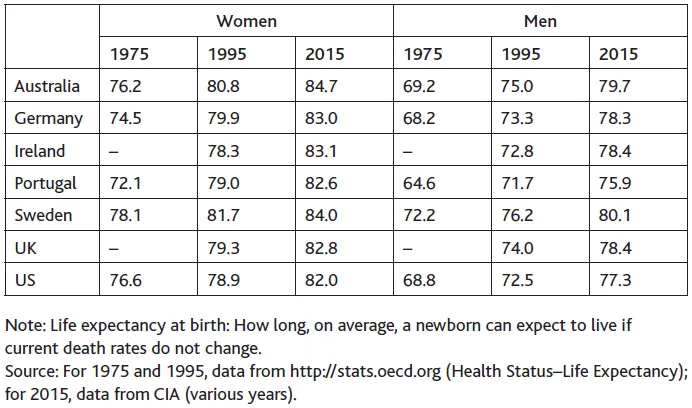

Live longer, work longer

It would be naive to assume that the national pension systems first developed in the early 20th century to provide retirement income for male industrial workers would necessarily be up to the task of meeting the retirement needs of 21st-century citizens. After all, both the proportion of the population old enough to be eligible for pensions and the expected duration of receiving pensions were much lower in the early to mid-20th century, when national state pension systems were widely implemented and matured (Street and Desai, 2016), compared to the opening decades of the 21st century. The human triumph of increased longevity has multiplicative effects that worry policymakers. First, because people are living longer, individuals who retire can expect to receive pension benefits for much longer periods than the architects of 20th-century pension systems anticipated. For example, in the early years of US Social Security (enacted in 1935), average life expectancy in the US was only 61, the number of years a typical Social Security recipient was expected to receive his pension was only a few years (Moon and Mulvey, 1996) and 6.9% of the US population was 65 or older. Similar interactions between the size of the older population and more years of life expectancy from 65 onwards have occurred in all affluent countries. As Table 1.1 shows, even in the past few decades, women’s and men’s life expectancies have increased in all the countries analysed in this book.

Table 1.1: Life expectancy at birth by gender (1975, 1995, 2015 estimated)

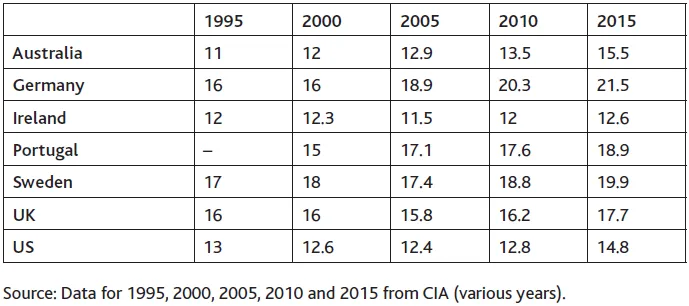

Beyond individuals living longer lives, the entire age structure of national populations has changed, from relatively young to ageing and older. The size of the aged population – the proportion of citizens old enough to have been traditionally entitled to public pensions – is relatively larger than at any time in human history and is still growing (see Table 1.2). Given that public pensions were designed and expanded in the early to mid-20th century, it is no surprise that a refrain first heard in the 1980s (Street and Quadagno, 1993), and that reverberates in even more policy circles now, is ‘too many, too expensive’.

Nearly every affluent country has a public pension system designed to provide stable income in old age after individuals withdraw from paid employment, institutionalising retirement and bestowing what John Myles (1989) called a citizen’s right ‘to stop work before wearing out’. Pension systems were designed by policymakers who took into account the economic, labour market, family structures and social conditions of their times. One circumstance that informed early pension policymaking was the age structure of national populations, that is, the proportion of ‘working-age’ adults (conventionally defined as those individuals between the ages of 15 and 64) to the much smaller proportion of ‘elderly’ (65 and older) citizens. In pay-as-you-go defined benefit pension systems, the dominant approach to 20th-century pension funding, workers’ contributions (earmarked contributions or other tax revenue) funded the state pensions for retirees.

Table 1.2: Percentage of national populations aged 65+

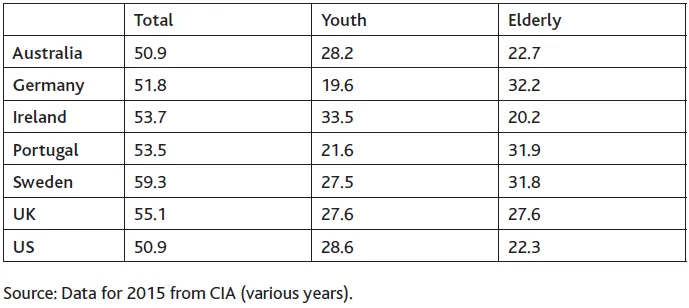

The balance between the size of the working-age and older populations has shifted over time. One measure of that is the dependency ratio (the proportion of children under 15 and adults 65 and older – presumed not to be employed – to adults aged 15–64), a shorthand way of representing different age groups in the population. According to its proponents, the dependency ratio reflects the ‘burden’ carried by citizens in working-age groups to sustain resources for ‘non-productive’ components of the population. The old-age dependency ratio is one statistic used to justify raising ages for pension eligibility and extending work. Table 1.3 shows estimates of total, youth and elderly dependency ratios for 2015.

Table 1.3: Dependency ratios (2015, estimated)

Dependency ratios reduce human social relationships to their lowest economic denominator. Dependency ratios do not consider investments or legacies, only value for ‘independent’ citizens assigned as earning power through employment. Other socially valuable activities, because they are not monetised as employment is, are beyond the scope of dependency ratios. Neither is the skewed distribution of wealth taken into account. Consequently, there are obvious problems with uncritically using dependency ratios to understand the possible implications of national age structures for labour forces – ranging from erroneous assumptions that many 15 year olds are routinely employed, or that most 15–64 year olds adults are employed but most 65 year olds are not, to the inability for dependency ratios to take unpaid and essential but non-monetised care work into account. Another flaw in dependency ratios is the fact that productivity increases have, at least until now, permitted fewer workers to support larger non-employed segments of the population in mostly non-problematic ways. It is not that dependency ratios are useless or unimportant for providing insights for policymakers about challenges confronting pension regimes; they serve as reminders of the shifting age structure of populations. However, dependency ratios used uncritically can be very misleading. Like so many other measures that are asserte...