![]()

SEVEN

The Netherlands and the crisis: from activation to ‘deficiency compensation’

Marcel Hoogenboom

Introduction

In the 1980s, the Netherlands was one of the first countries in Western Europe to adapt its industrial unemployment provision system to the requirements of a new ‘post-industrial age’ (Clasen and Clegg, 2011a). By drastically reforming the unemployment insurance system, it was opened up to a growing number of temporary, flexible and part-time workers in the tertiary sector (Hoogenboom, 2011). In the next decade, by means of several labour law reforms, the Dutch labour market was made more flexible, resulting in rapidly growing numbers of temporary and part-time workers, as well as self-employed workers without employees (De Beer, 2011).

In the same period, the Netherlands also became one of pioneering countries in the development of ‘activation policies’ in the European Union (EU), that is, of active labour market policies (ALMPs), which, unlike ALMPs in earlier times, combine ‘incentive reinforcement and employment assistance’ (Bonoli, 2010: 450). In the late 1990s, huge investments in activation policies caused government spending on ALMPs to rise from 0.3% of gross national product (GNP) in the late 1980s to more than 0.5% in 2000. Although the proportion fell to 0.4% in the early 2000s due to falling unemployment rates and cutbacks imposed by centre-right governments on ALMP spending, the Netherlands remained one of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries spending most on ALMPs (OECD, 2007).

However, in the years preceding the 2008 financial and economic crisis, enthusiasm for both flexibilisation and activation had cooled in the Netherlands. Trade unions and populist political parties warned about the insecure position of the rapidly growing number of employees with precarious jobs and of involuntary self-employed workers without employees. Under electoral pressure, the centre parties also gradually withdrew their support for further flexibilisation of the Dutch labour market and cutbacks in unemployment protection.

At the same time, the results of the new activation programmes, which were basically meant to compensate for the growing flexibility of the Dutch labour market by facilitating job-to-job mobility, turned out to be disappointing. While on the eve of the financial and economic crisis in the Netherlands, the contours of a new ALMP paradigm were discussed, its implementation was thwarted by the consequences of the crisis for the government budget. During 2008–14, as a result of attempts to reduce government spending, activation programmes in both unemployment insurance and social assistance were run down. However, it will be claimed in this chapter that a new ALMP paradigm is emerging in the Netherlands, which I will dub ‘deficiency compensation’. In this new paradigm, ALMPs are no longer directed at removing individual skill deficiencies by means of training and schooling programmes (as in activation), but directed at accepting and financially compensating these deficiencies. As regards unemployment provision programmes and job protection law in the Netherlands, surprisingly little was changed during the crisis. In this chapter, this absence of reforms is attributed to a ‘silent uprising’ on the part of the low and lower-middle classes. Through their support for two new political parties in the Dutch Parliament and a change of course by the largest trade union in the Netherlands, they prevented the main political parties from implementing new reforms after two decades of fundamental change in Dutch unemployment provision and job protection systems.

The chapter is structured as follows. The consequences of the financial and economic crisis that hit the Netherlands from the autumn of 2008 are briefly sketched in the second section. In the third section, the reform of the Dutch unemployment provision system in the period between 1980 and 2008 is analysed in order to be able to understand what happened afterwards. In the fourth section, the emergency measures in the two years of the crisis are discussed, while in the fifth section, the policy reforms in the unemployment provision and job protection systems that were implemented in reaction to the crisis are described and analysed. The final section contains the conclusion.

The consequences of the crisis and early policy reactions

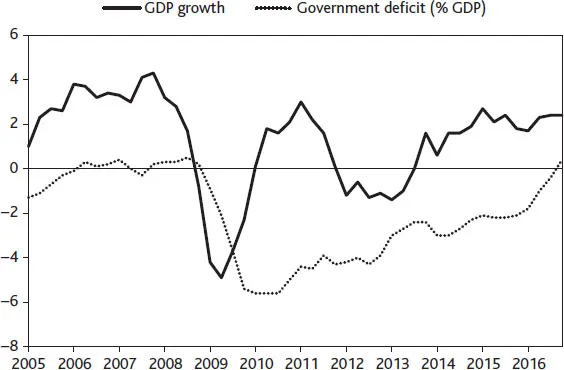

As in many other Western countries, the financial crisis in the Netherlands really started with the fall of the Lehman Brothers bank in September 2008. While in the months preceding it, Dutch real gross domestic product (GDP) had been growing by about 2% annually, after that, economic contraction set in rapidly. In the last quarter of 2008 and in 2009, the Dutch economy shrank by about 4% (see Figure 7.1). One of the main causes of this downturn was the economy’s heavy reliance on the financial sector, real estate and construction. With world players such as ABN-Amro Bank and ING Bank, in 2007, the balance sheet of the Dutch financial sector was about four times as large as Dutch real GDP, while homeowners owed almost €500 billion (or almost 100% of real GDP) to these banks (CPB, 2008). Therefore, the fall of Lehman Brothers set in motion a chain reaction that brought economic growth to a halt for years to come.

The fall of Lehman Brothers was almost immediately followed by acute solvency problems among some of the largest Dutch banks. In October 2008, the Dutch state rescued ABN-Amro by buying all its shares and taking full control of its activities in the Netherlands.1 A few months later, the state rescued other banks by providing them with large capital injections. In this period, the total amount of money spent by the Dutch state to save the financial sector amounted to about €30 billion or 5% of real GDP (CPB, 2008).

A direct consequence of the crisis of the Dutch banking system was a drying up of loans for Dutch consumers and business. As for consumers, the crisis particularly prevented the banks from providing the lavish mortgages that, during the previous two decades, had inflated house prices substantially in the Netherlands. As a result, real estate and construction also went into crisis, while falling house prices led consumers to curb their spending, repay debt and try to increase their savings. When, in 2009, the financial crisis was transformed into a worldwide economic crisis, the Dutch economy went into a slowdown that, with a short upswing in 2010–11, lasted for almost five years (see Figure 7.1).

For the government budget, the financial and economic crisis had major consequences. While successive government coalitions, from both the Left and the Right, had made great efforts to reduce the government deficit after the economic crisis of the 1980s – finally resulting in a balanced budget in 2006 – in the course of only one year, this effort was nullified by the crisis, which converted a 0.2% surplus into a 5.6% deficit. Topped up by the large sums that the government spent on bailing out the banks, government debt – another preoccupation of subsequent government coalitions in the previous three decades – grew from 43% in 2007 to 57% two years later. Ultimately, it would grow to 65% in 2015.2

Figure 7.1: Real GDP growth and government deficit in the Netherlands, 2005–16 (% of GDP)

Source: www.statline.nl (accessed 26 July 2017)

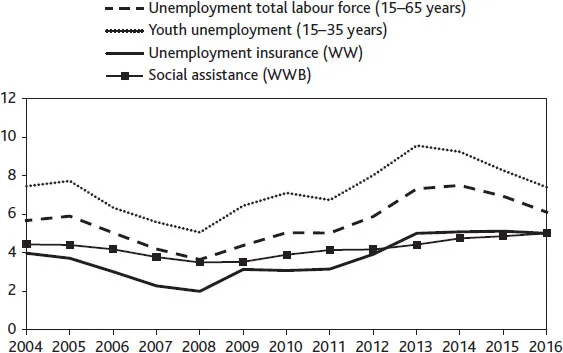

However, in line with the international trend in the early days of the crisis, the first reaction of the government at the time – the Balkenende IV government, a cabinet coalition of Christian Democrats (CDA) and Social Democrats (PvdA) (for details, see Table 7.1) – was not to cut back expenditure (Den Butter, 2009). The government’s main fear was that cutbacks in spending would accelerate the growth of unemployment, which was already growing substantially in the first months of the crisis (see Figure 7.2).

Table 7.1: Dutch governments, 2007–16

Government coalition* | Term | Coalition partners |

Balkenende IV | February 2007–October 2010 | CDA (Christian Democrats)

PvdA (Social Democrats)

CU (Orthodox Protestants) |

Rutte I | October 2010–November 2012 | VVD (Conservative Liberals)

CDA (Christian Democrats)

PVV (Right-wing Populist)† |

Rutte II | November 2012–present | VVD (Conservative Liberals)

PvdA (Social Democrats) |

Notes:

* Named after prime minister.

† Formally, the PVV was not part of the government coalition (there were no PVV cabinet ministers), but it gave parliamentary support to the coalition.

Figure 7.2: Unemployment total labour force (15–65 years of age) and youth unemployment (15–35 years of age); and benefit recipients of unemployment insurance and social assistance, as a percentage of the labour force, 2004–16

Source: Calculated on the basis of data from: www.statline.nl (accessed 26 July 2017)

Apart from the measures mentioned earlier, the government reaction to the economic crisis and its consequences was rather passive. It trusted that the first dramatic consequences of the crisis for the Dutch economy would ebb away as a result of the so-called ‘automatic stabilisers’. The latter term refers to government budget doctrine, adhered to by Dutch government coalitions since the mid-1990s, which states that in order to prevent a pro-cyclical effect of government spending in times of economic downturn, spending on planned government policies should not be immediately cut if tax revenues dwindle as a result of the economic downturn.3 The doctrine also states that when the economy recovers, extra government revenues should be cut in order to compensate for government debt built up during the economic downturn (Den Butter, 2009).

Even without the doctrine, the government had to prepare for severe budget cuts because, already in early 2009, the government deficit was in violation of the 3% Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) criterion. Therefore, in spring 2009, 20 interdepartmental working groups of civil servants were asked to come up with proposals for cutbacks that would reduce spending below the EMU criterion in the years to come. When the proposals of the working groups were published only a few months later, it became clear that in order to comply with the criterion, government spending had to be cut by about €50 billion, or 15% (Inspectie der Rijksfinanciën, 2010).

The reports of the 20 interdepartmental working groups sent shock waves through Dutch society. At once, it became clear how deep the crisis was, how brutal future cutbacks in social security and job protection would be, and how serious the ramifications would be for all citizens in the years to come. However, before the working groups had even published their advice, in February 2010, the Balkenende IV government coalition fell because of a disagreement between the CDA and the PvdA over the deployment of Dutch troops in Afghanistan. Over the next five years, two successive government coalitions (Rutte I and II) implemented many of the cutback programmes that the working groups had proposed, causing the Dutch government deficit to reach the EU threshold of 3% of real GDP in 2014.

The cutback programmes contained a wide variety of policy measures, which affected virtually all categories of Dutch citizens. Among these measures were many welfare state retrenchments, such as a gradual extension of the retirement age from 65 to 67 years, large cutbacks in long-term care budgets, a limitation of tax cuts for homeowners and the replacement of the national student scholarship system by a system of student loans (Parlement, 2012). However, unlike in many other EU countries, in the Netherlands, the cutback policies that were implemented left the unemployment provision system largely untouched. Indeed, in the period 2008–16, parts of these systems were thoroughly reformed, but they were not merely reformed in reaction to the crisis or aimed at cutting back expenditures. The reforms were already planned before the beginning of the crisis, which, at best, accelerated their implementation. The same was true of ALMPs. In the period 2008–14, ALMP policy budgets were cut severely; however, again, this was not so much in reaction to the crisis or its consequences for the state budget, but merely a continuation of pre-crisis policy trends.

Reform of the Dutch unemployment provision system and active labour market policies up to the crisis (1980s–2008)

The main reason why unemployment provision in the Netherlands was largely exempted from retrenchments was that, according to most political parties in the Dutch Parliam...