![]() Part 1

Part 1

Theories of ageing and globalisation![]()

TWO

Theorising time and space in social gerontology

The themes of time and space occupy a central place within social gerontology (Baars 2015), however, these are generally implicit and often poorly theorised by researchers and writers in the field. Yet the ways in which we understand time, space and the interconnections between them impact on the ways we frame ageing and later life. As conceptions of time and space change so too do our theories of ageing. As a result, it is important to critically assess the time-spaces employed in social gerontology if we are to understand the potential impact of globalisation on contemporary ageing. In this book we use the term time-space to refer to how spatial and temporal regimes are interconnected and constitute one another at both the material and symbolic level. These time-spaces produce and are reproduced by a set of dominant ideas, practices and discourses. The transition from one time-space to another is reflected in a change in the relationship between these two constituent parts and leads to changes in the social, cultural, political and economic practices that were underpinned by the previous system. Therefore, those gerontological theories that were developed around earlier time-spaces focused on the nation state are being challenged by the emergence of new forms of space, from the local to the global. To explore what this means for our understanding of later life and for older people themselves we need to move away from the conventional narrative about the development of social gerontological theories and re-examine them in terms of the temporal and spatial frames which they deploy.

Social gerontology represents a broad church (Moody 2000, Victor et al 2007, Phillipson 2013a). It spans a range of disciplines from the biomedical through to the arts. Indeed, having been criticised for most of its history for being data rich but theory poor (Bengtson et al 1997, Harper 2000, Alley et al 2010), social gerontology is now faced with a seeming embarrassment of theoretical riches. However, the connection to empirical studies has not always as strong as it might have been (Hendricks et al 2010). Moreover, the changing terminology and often fuzzy theoretical boundaries have made it difficult to present a comprehensive and unambiguous picture of the state of theory within the subject. Nonetheless, it is possible to discern a conventional narrative of the theoretical developments within social gerontology. Phillipson and Baars (2007) have presented what could be described as a fairly orthodox version in which they identify three key phases in this development. The early phase, from the late 1940s to the 1960s in which ageing is seen as an individual and social problem, is characterised by activity theory and disengagement theory. In the middle phase, from the 1970s to the 1980s, ageing is seen as socially and economically constructed. This is a more diverse moment and includes modernisation and ageing theory, life course and age stratification perspectives before moving onto to structured dependency and political economy of ageing approaches. The present phase, from the 1990s onwards, is dominated by cultural and critical gerontological perspectives. They argue that these phases and the shifts between them reflect the different ways in which the relationships between older people and social institutions has evolved.

Time-spaces of ageing and later life

This conventional narrative provides a useful framework for exploring the historical development of social gerontological theories as well as setting the parameters of the debate about the meaning of later life. However, the framework leaves issues of time and space implied or neglected. Yet time and space form the twin axes along which ageing and later life are constructed and understood in all societies.

From a relatively conventional, but not uncontested, sociological approach to history it is possible to identify two relatively recent periods in history (Giddens 1991a, Francis 1992, Smart 1992). These are classified here as first modernity and second modernity (Beck and Lau 2005). Although this periodisation is generally formulated within a European context one can also see evidence of this shift in non-Western societies such as China, Japan and those of the Middle East (Elliott et al 2014). However, while debates about the presence and persistence of non-Western forms of modernity are important (Eisenstadt 1999, 2000, 2002), it is clear that many of the features of first modernity coalesced most clearly in Europe and America. In addition these nations were also critical in the export of modernist ideas and practices especially as a result of their colonial and imperial activities (Appadurai 1996, Wagner 2015).

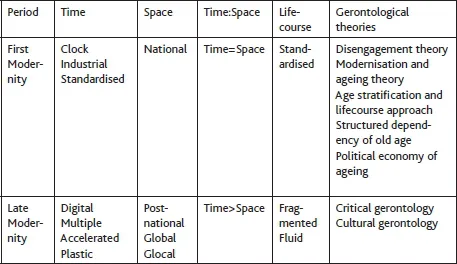

It is important to note that each of these historical periods is embedded in its own temporal and spatial regime which produces and reproduces theories of ageing. Consequently, instead of viewing the development of social gerontology as an unfolding linear narrative, it is possible to identify two broad families of theories. Theories in each family share a similar set of temporal and spatial assumptions while differing from those in the other group. In the first group are the modernist views of ageing. This category contains disengagement theory, modernisation and ageing theory, age stratification and life course approaches, structured dependency theory and the political economy approach. The second group can be seen as representing the late modern take on ageing and includes both cultural and critical gerontological perspectives.

Modernist approaches to ageing and old age

Social gerontological theories of the mid to late 20th century reflected the temporal and spatial logics of first modernity. Giddens (1991a) identifies three key, interconnected, elements of modernity that set it apart from ‘traditional’ societies. These are the separation of time and space, the disembedding of social institutions and institutional reflexivity. He argues that, although all societies develop schema for understanding and organising time and space, in pre-modern societies ‘time and space were connected through the situatedness of place’ (1991: 16a). Modernity breaks this connection by emptying out time and disconnecting space from place. Another key factor in this separation was the disembedding of social institutions which Giddens (1991a: 18) defines as the ‘lifting out of social relations from local contexts and their re-articulation across infinite tracts of time-space’. The principal institution that emerges from this process is the nation state that has sovereignty and ultimate authority over a given geographical area. Modernity also ushered in a new conceptualisation of time as abstract, linear, future oriented and measurable. Hence the rail networks that developed throughout the 19th century did more than simply connect space; they also coordinated time. Until then, village clocks, where they existed, were set and regulated locally, usually in relation to the sun, creating a great number of different local times within a given country. The coming of the train, and improvements in mechanical motions, meant that all clocks were steadily synchronised to ‘railway time’ (Giddens 1991b). Alongside this was the shift from the farm to the factory that not only created a new class of workers, it also replaced older temporal frames, of what Hareven (1994) calls ‘family time’, with a new, harsher, abstract ‘industrial time’. These changes to the way in time and space were conceived had a radical impact on the organisation and conceptualisation of the life course. The modern life course emerged around the partition of life into three mutually exclusive, sequential stages of education, work and leisure (Elder 1975, Mayer and Schoepflin 1989, Hareven 1994, Settersten and Mayer 1997). Following these arguments, it is possible to group together a number of gerontological theories that use these referents, of the nation state and the standardised life course, to frame ageing and later life (see Table 2.1). The relative salience of time or space varies according to the primary focus of the different theories. Life course theories have clearly privileged the temporal dimension while structured dependency theory is arguably more focused on the spatial. However, all were based upon the notion of a standardised, fixed, linear life course and took the nation state as the key spatial reference.

Table 2.1. The spatial and temporal regimes of modern and late modern societies

Disengagement theory

Disengagement theory probably best illustrates the taken-for-granted nature of assumptions about time and space employed by these early modernist theories (Facchini and Rampazi 2009). In Cumming and Henry’s (1961) Growing Old: The Process of Disengagement, retirement, as a process and a status, is seen as a functional response for both the individual and society to older age. Retirement was believed to function for the individual, much like the ‘sick role’ did for medicine (see Parsons 1955, Williams 2005), by offering a socially sanctioned non-economically productive role. It was argued that this allowed older (male) workers to withdraw from employment without feelings of shame or inadequacy. This same process provided a social function by freeing up labour market positions for younger workers with new skills and ideas. Bromley (1981: 134–5) gives an account of this approach:

One of the more obvious features of maturity and old age is social disengagement – a systematic reduction in certain kinds of social interaction … It is normal in late maturity and encouraged by common social practices such as superannuation, limited terms of office, age limits and many social norms and expectations affecting behaviour … The process looks like a sensible attempt on the part of the older person to distribute his [sic] reduced energies and resources over fewer but more personally relevant activities, to conserve effort and to escape from demands which he cannot or does not wish to meet.

Here we can see a considerable degree of similarity between functionalist ideas of the division of labour in society, with each person fulfilling their specific role, and the idea of the division of time within the life course, each period having its specific requirements. Early life is a period of socialisation. This is followed by mid-life, in which each citizen fulfils their (re)productive duties. Finally, the end of life is when individuals should withdraw from these activities. In this model retirement is not only a matter of individual biographical timing, it is part of a wider structure of social timing. Withdrawal from work and other activities is underpinned not just by social policies, around retirement for example, but by normative expectations of disengagement. It is the assumption that there is an affinity between individual and social calendars that leads to the conclusion that retirement represents both an individual and a social good.

Similarly, disengagement theory collapses the spatial distinction between the individual and society. Looking back on this theory from our historical location it is possible to identify a tension between the individual and social processes at work. However, in line with functionalist sociology the authors saw no such tension. For them what was good for the individual was good for society and vice versa. Thus, as Phillipson and Baars (2007) note, from this perspective retirement ceases to be (solely) an individual decision but it becomes a social problem. For functionalists in particular, but also for sociologists in general at this time, this meant it became a problem for the nation state. Thus retirement was seen as crucial for the health and productivity of the nation because it opened up employment opportunities for cohorts of young workers.

Life course and age stratification approaches to ageing

Of the all the theories identified within this modernist group, it is the life course theories as well as the age stratification approach which appear, prima face, to be most explicitly concerned with the temporal frames through which ageing and later life have been constructed. Advocates of the age stratification approach have argued that age classifications are not static, rather societies are composed of a number of age strata, made up of children, teenagers, middle-aged adults, and so on, which were dynamically interconnected (Riley 1971, 1973, 1974, Foner 1984). These strata were not fixed but were composed of different cohorts. Thus differences between age strata could be due as much to the different historical experiences of each cohort as any age related factors. For Ryder (1985) these birth cohorts, and their succession, were the ‘demographic metabolism of society’. Each member of a birth cohort, which Ryder defined as ‘those persons born in the same time interval and aging together’ (1985: 12), occupies a ‘unique location in the stream of history’. As each cohort enters these age strata they confront pre-existing age related norms and sanctions. These are the relics of past cohorts and bear the imprint of their historical experience. Thus each new cohort, forged during a different time, will seek to challenge these boundaries and assert their identity as an age group.

Writers from a life course perspective developed similar arguments although their focus was on the individual rather than on the cohort. They argued that in order to understand the situation of older people it was necessary to look at the entirety of their lives, along multiple dimensions such as work, family and housing, and the advantages and disadvantages that they had encountered (Elder 1994, Berney and Blane 1997, Blane et al 1999, Holland et al 2000, Dannefer 2003, Blane et al 2004, Ferraro and Shippee 2009). Of equal importance, and what distinguishes this approach from Eriksonian life stage theory, was the insistence on locating the timing and trajectories of the life course for different cohorts within their, different, historical contexts (Elder 1975, 1994, 1998, Gilleard and Higgs 2015).

Although the reliance on the notion of a standardised life course is obviously more explicit among these life course theories, it occupies an equally important place in the ideas of the age stratification approach as well. The life course approaches that are used in gerontology, as well as elsewhere (see Ben-Shlomo and Kuh 2002, Kuh et al 2003 for epidemiological uses), assume that individuals pass through a series of successive stages leading to later life. The number of stages in this sequence varies somewhat but generally corresponds to the familiar pattern of the ‘three box model’ of early life, education, employment and finally retirement (Dannefer and Settersten 2010). The recognition that there are differences between people as they age, accumulating advantages or disadvantages, contrasts with the use of fixed ages at which to explore these differences. The awareness of variable life trajectories is predicated upon an established, standardised life course. To employ a sporting metaphor, we may all run the race better or worse but we do so along the same course.

This holds true for age stratification theory too. While the primary temporal unit in this theory is the cohort a similar dynamic is evident; in this case it is successive cohorts who encounter and pass through these life stages rather than individuals or social classes. Thus the ‘churning’ that Ryder (1985) refers to is the result of the tension between demographic change and a pre-existing, established life course. Consequently, these theories rely on the standardised life course and (re)produce an image of old age as clearly defined and different from other age groups.

Both approaches also operate with a similar, although less explicit, spatial frame. These trajectories and transitions take place within the nation state. While the basic tripartite model of the life courses is generally seen as a common feature of Western societies at least, there is also an acknowledgement that the exact spacing of these temporal units differs between nations. Each country will have slightly different ‘status passage’ points because of variations in both social policies and cultural norms. For example in Europe there are differences in the ages at which individuals enter and leave formal education (Eurydice 2011). Similarly, the age at which people can retire from the workforce varies considerably between countries (OECD 2013). Given the importance of retirement in demarcating the beginning of later life for each of these theories, these national variations in social policy imply a state centric approach.

Similarly, from an age stratification perspective, differences in the culture and history of each country signify that the experience of each cohort is not only time specific, but is also space specific. It is often the unique nature of the national experience that defines one cohort from the next. For example, the fall of the Berlin Wall or the Vietnam War might act as a defining moment separating one cohort from the next within a specific country.

Modernisation and ageing theory

Modernisation and ageing theory also has the nation state as its primary spatial frame. Despite their focus on the ‘global’ trend towards the, apparently inevitable, modernisation of societies, Cowgill (1974) and Cowgill and Holmes (1972) rely on the nation state as the unit of comparison against which ‘progress’ towards this end can be measured. A central argument is that the societies of the ‘developing’ world will gradually come to resemble those of the ‘developed’ world. As a consequence, the status of older people becomes diminished. As noted earlier a key feature of modern society is the emergence of the nation state and as such societies can be compared with one another on the basis of their level of modernisation. This means, in part, that comparison can be made depending on the degree to which they are governed by a rational, bureaucratic, nation state rather than relying on traditional, local, tribal or kinship structures (Lerner 1964). The connection between theory and spatialisation is paramount.

Modernisation and ageing theory also rests on a ‘dual’ temporality. The first temporality is the overarching modernisation process. This reflects the broader modernist, scientific, Enlightenment notions of progress. As Massey (2008) has argued such approaches, by seeking to locate nations along a continuum of traditional to modern, represent time as space. From the perspective of modernisation and ageing theory, countries in the developing world appear as manifestations of developed nations at earlier stages in their history. The second temporality refers to the concomitant reorganisation of time within the nation state. One of the central characteristics of modernisation, according to its advocates (Lerner 1964, Inkeles 1969, 1998), is the emergence of policies governing the management of the life course. This is particularly evident in the development of, and participation in, formal education. A key indicator for this has been the employment of those of ‘working age’ in the formal (non-agricultural) sector. Cowgill and Holmes (1972) saw modernisation as a shift from the natural rhythms of ‘family’ time, in which older people were venerated, to the artificial, impersonal, dictates of ‘industrial’ time, which privileges the young. The spread of new technologies was also believed to disadvantage older people by devaluing their skills and experiences, which had developed during different times and the creation of new jobs for which they were ill-equipped. Similarly older people were also seen to be excluded from the spread of education as this became connected with childhood (Palmore 1971, Cohen 1994). In this view the emergence of retirement constituting the end of working life was seen as disastrous for older people, robbing them of both status and power. The progress of nations along the path of modernisation seems to inversely parallel the individual’s forlorn journey to the industrial scrap heap of ‘old age’. Both pathways reflect and reinforce the dominant temporal trope of modernity. Time is organised, standardised, linear and irreversible.

The structured dependency of old age: the institutionalisation of time and space

In a similar manner to modernisation and ageing theory, Townsend’s structured dependency theory focused on the marginalisation of older people. However, it was also an analysis of the increased institutionalisation of the time and space of old age. He points to three key policy areas that have been responsible for this: retirement, pensions and residential care (Townsend 1981). Hence his work can be read as a description of the consequences of the struggle between competing spatial and temporal regimes for older people. In his seminal work The Family Life of Older People (1963), Townsend presents a picture of later life in the East End of London in the 1950s that was still largely localised but rapidly undergoing change. Central to this study were the negative consequences of the dissolution of kin-based community networks for older people. He explicitly situated the ‘problem’ of old age in a wider, political, debate about the shift away from the provision of care for older people by the family to care by the state. This transformation can be seen as a reflection of the shift from the spatial and temporal regimes of pre-industrial society to those of an industrial, modern, society (Townsend 1963). Although the majority of the older respondents in Townsend’s study did not live with their adult children they lived in close proximity to them. They reported being in frequent contact, usually in person and often several times a day. Townsend argues that these dense kinship networks, especially in the form of regular contact between mothers and daughters, were crucial for maintaining the independence of older people. These kinship networks were overlaid with community and class relations. Although logically separable, in the East End of London during...