![]()

SECTION VII

Changing demographics and ageing populations

![]()

41

Growing old gracefully

Lives curtailed are usually shortened by a series of insults rather than a single tragic event. Whether you get to grow old gracefully or die young depends, today, as much on where you grow up in Britain as it did a century ago.

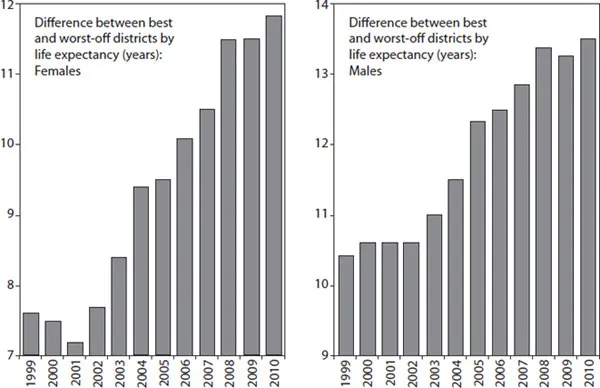

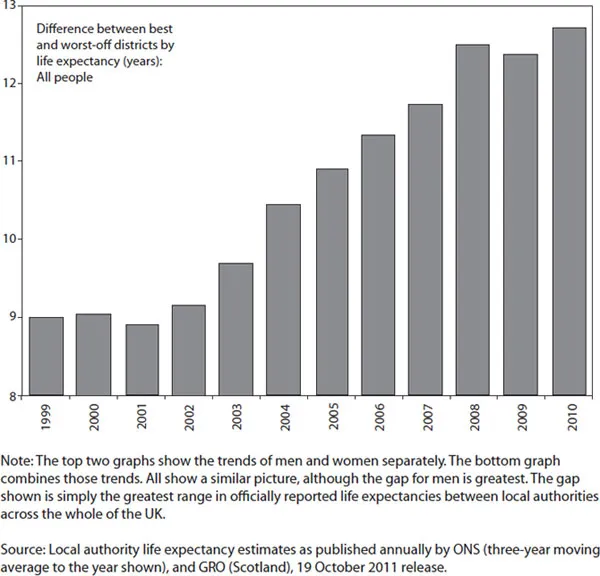

Just over a century ago (some time shortly before 1920) was the last time when life expectancy gaps between areas were as large as they are today. Back then almost everyone lived shorter lives, but by 1936 they had also learned from the First World War, from the revolution in Russia, from the 1929 economic crash and during the 1930s depression, that they really could be ‘all in it together’. In 1920, although hardly anyone realised it then, improvements had already begun. But a long human lifetime later, during 2012, life expectancy gaps had again grown to be greater than in 1920, but maybe not as great as in 1912.1

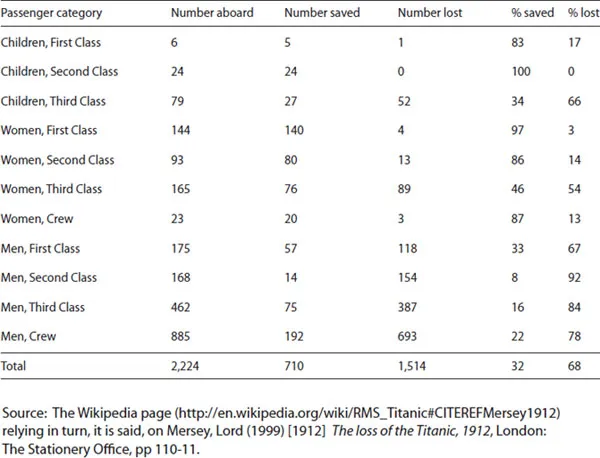

When today’s centenarians were born

A single event, such as the sinking of RMS Titanic, brought into sharp focus the distinctions between social classes in 1912, and the need for all three social classes to be properly accommodated on a ship crossing the Atlantic. As contemplated by the Singaporean children shown in Figure 41.1, lists of the survivors and the deceased reveal that the passengers’ segregation on board ship and their unequal access to lifeboats meant that while two thirds of first-class passengers survived, only half of second-class and a minority of third-class passengers (and crew) were rescued. Up close, the first names of the survivors and dead will have revealed the gender balance, but it was not all ‘women and children first’ – a third of the first-class men also survived (see Table 41.1).

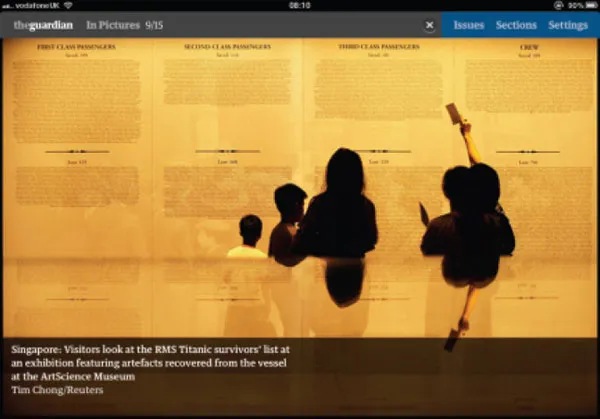

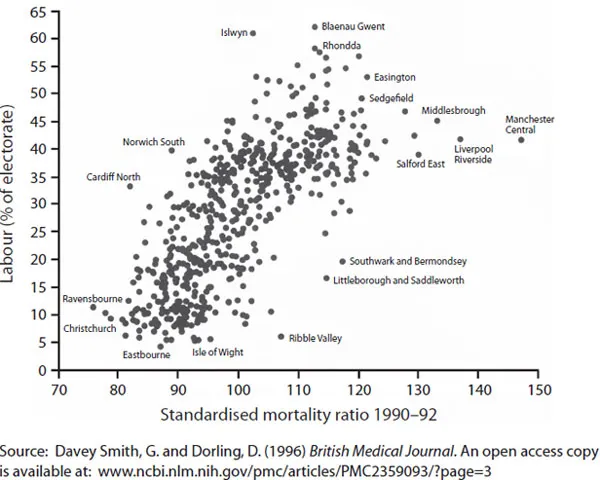

Some 80 years after the Titanic sank, social divisions in British society were clearly seen to have been growing again. In the 1992 General Election John Major’s Conservatives won a majority despite (the then) 13 years of Conservative misrule. It was the people who lived in the places that enjoyed better health who supported the Conservatives most strongly in that fateful election (see Figure 41.2). The outcome of the 1992 General Election arguably resulted in the rise of New Labour, a party that then failed during its 13 years of rule (1997–2010) to prevent health inequalities growing even greater. We are currently waiting for the population data that will allow us to assess the last couple of years of New Labour’s reign. It is not impossible that there was an improvement in inequalities towards the end, but it is impossible that that will have done anything other than to slightly curtail the rise in inequalities since 1997, itself a continuation of the social segregation that began in earnest in 1979.

Table 41.1: Casualties and numbers saved by age, sex and class on RMS Titanic, estimates produced by the British Board of Trade report.

It is worth comparing Figure 41.2 with Figure 39.1 in Chapter 39, which shows how recently the correlation between deprivation and mortality has become a little weaker than that between voting and mortality (for very similar parliamentary constituencies). Voting patterns can reflect past traumas as well as current circumstances. The pattern of voting that occurred in 2010 saw the country become even more politically divided than before, as the greatest swings to the Conservatives occurred where health had been least damaged and the Conservative vote had been highest to begin with. Those parts of Britain that had suffered the most from growing division actually saw the share of the electorate voting Labour rise. It was similar in 1992 although then, because the country was less polarised, the Conservatives won an outright majority of seats (see Dorling and Thomas, 2011, p 50).

Figure 41.1: The survivors and deceased lists by social class, Titanic, 1912, viewed in 2012.

What’s worse, they don’t care, either

Twenty years on from the 1992 General Election, and as numerous commemorations of the Titanic’s sinking were taking place worldwide, under the surface of these commemorations was the uncomfortable recollection that the tragedy may have been as great as it was because there were only enough lifeboats for a fraction of the passengers. It was not just that the ship was thought unsinkable; it was that many of its passengers and crew were not considered a priority in planning for such an event. This has echoes in our present. The journalist John Harris has tried to explain how similar class prejudice and ‘stupidity’ remain in Britain:

Note also the words of backbencher Nadine Dorries, whose Liverpudlian dad was a bus driver: “The problem is that policy is being run by two public schoolboys who don’t know what it’s like to go to the supermarket and have to put things back on the shelves because they can’t afford it for their children’s lunchboxes. What’s worse, they don’t care, either.” A saga is being played out, bound up with the enduring qualities of the English ruling class, and a mixture of gentry and parvenus (and, in Osborne’s case, people stuck somewhere in between) who are failing power’s most basic tests.

It has all reminded me of the words of brilliant Old Etonian George Orwell, in 1941: “It is important not to misunderstand their motives, or one cannot predict their actions. What is to be expected of them is not treachery, or physical cowardice, but stupidity, unconscious sabotage, an infallible instinct for doing the wrong thing. They are not wicked, or not altogether wicked; they are merely unteachable. Only when their money and power are gone will the younger among them begin to grasp what century they are living in.” (Harris, 2012)

Figure 41.2: Scatterplots of Conservative and Labour voting in 1992 against all age-standardised mortality ratios, 1990-92.

John Harris was writing in the immediate aftermath of the March 2012 Budget, what came to be called the ‘Omnishambles’ Budget. A conspiracy theorist might imagine that it deliberately contained so many policies that quickly had to be abandoned so as to avert attention from how it reduced tax-takes on the incomes of the rich, and reduced corporation taxes on the profit-take of the companies they owned and on their wealth (when the ‘charity giving’ proposals to reduce tax-dodging were abandoned). But no one could have had the foresight to have so carefully engineered such a spectacular cock-up. And it was not just the Chancellor’s cock-up.

The Chancellor at least had taken a slightly different degree at university than almost everyone else involved in the public discussions – a reader of the same newspaper had commented just two days earlier, that:

As I watched the BBC coverage of the budget I was struck by the rich educational diversity of our politicians and pundits. Coalition: Osborne (history, Oxford), Cameron (PPE [Philosophy, Politics and Economics], Oxford), Hague (PPE, Oxford), Alexander (PPE, Oxford), Clegg (anthropology, Cambridge). Labour: Miliband (PPE, Oxford), Balls (PPE, Oxford). Pundits: Flanders (PPE, Oxford), Robinson (PPE, Oxford), Peston (PPE, Oxford). Strength in diversity? (Greenhaigh, 2012)

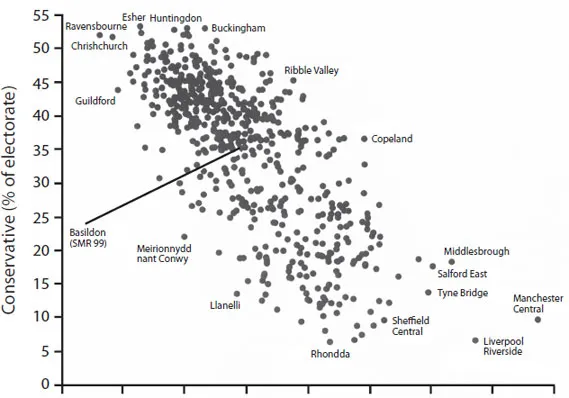

In Britain health inequalities are so high not simply because ‘policy is being run by two public schoolboys’. They were high and rising before that. They rose under Kesteven and Grantham Grammar School girl Margaret Thatcher’s reign in office, stalled slightly under Rutlish Grammar School boy John Major’s period of tenure, climbed during public school boy Tony Blair’s years of office and perhaps stalled again during Kirkcaldy High School boy Gordon Brown’s brief reign. Trends since 1998 are shown in Figure 41.3. It was not so much these leaders’ segregated schooling2 that is to blame, but the segregated schooling of so many they meet and work with in politics. This segregation is amplified by selection to university and then to courses and colleges within just a few universities. Just a few days later in the same newspaper it was explained that:

The PPE clones often mate with lawyers in their attempt at world domination. They reaffirm each other’s intellectual capacity by rarely deviating from the path. That path usually means a deference to the institutions which produced them and thus, at the top of the system, we have mind-numbing uniformity.… Education policy is made by those who loved it, and this is a fundamental mistake. People who never regarded school as a moronic prison full of inane rules should not be in charge of them. This is why, instead of looking to the future, the current fashion in education is to look only backwards. (Moore, 2012)

Figure 41.3: A measure of social integration between geographical areas: life expectancy estimates diverging in the UK, 1999-2010.

Were a small bunch of educationally segregated or otherwise socially segregated rich men steering the economy (as much as it was being steered) and reserving the lifeboats mostly for themselves? Is it because so many of them see it as in their personal self-interest to try to ensure that up to 49 per cent of beds in NHS hospitals are privately run that they push through policies such as the Health and Social Care Bill? Do they not want to mix on wards with poor people when they are old or ill just as they did not mix when they were young and well? Coalition government Ministers, MPs and supporters in the House of Lords appear to prefer to see parts of the NHS face bankruptcy and become available for rapid privatisation.

On Tuesday, 26 June 2012 it was announced that South London NHS Trust was being taken into administration. It was the first part of the NHS to go bankrupt in this way. The trust had brought mortality rates down from above the national average to below average in many poorer parts of London. It had done this within just a dozen years, but the lives that were prolonged were not the lives of the affluent.3

There are alternatives to NHS privatisation if a Minister wishes to avoid sharing a ward with the poor when they are old and fall ill. This is because Ministers have the power to redistribute wealth and opportunity. They could choose a fairer future for all, where fewer people are either very rich or very poor. This occurs in all other Western European countries. Ministers are able to reduce poverty. During early 2012 it was reported that just £20 million a year would have been enough to have ended the very worst child poverty in Britain. The mechanism to do this would simply be for a Minister to sign an order that would result in pressing a switch on the benefits computer. Currently some 10,000 children whose families are seeking asylum in Britain h...