![]()

PART 1

The demographic and welfare-state contexts of grandparenting

![]()

TWO

The demography of grandparenthood in 16 European countries and two North American countries

Rachel Margolis and Bruno Arpino

Introduction

Intergenerational relationships between grandparents and grandchildren can offer tremendous benefits to family members of each generation. For grandparents, grandchildren are often important sources of emotional meaning and support (Silverstein and Long, 1998), and can have positive effects on physical and mental health and cognitive functioning (Arpino and Bordone, 2014; Di Gessa et al., 2016; Szinovacz and Davey, 2006). For grandchildren, grandparents can offer important inputs for social development or economic wellbeing (Chan and Bolivar, 2013; Knugge, 2016; Silverstein and Ruiz, 2006). The middle generation also often benefits from grandparents and grandchildren spending time together and receives important support with childrearing (Aassve et al., 2012; Arpino et al., 2014; Igel and Szydlik, 2011).

When grandparenthood begins and how long it lasts are determined by the demography of the family (Arpino et al., 2017; Margolis, 2016). The transition to grandparenthood occurs when one’s child becomes a parent for the first time. Unlike becoming a parent and many other life-course events, the transition to grandparenthood has been labelled a countertransition (Hagestad and Neugarten, 1985) because its occurrence and timing are not determined by the persons themselves but rather by their adult children and their partners’ transition to parenthood. The length of grandparenthood is the period of time that begins at the birth of one’s first grandchild until the end of the grandparent’s life (Margolis, 2016). At the population level, a variety of social and demographic factors affect when grandparenthood generally starts, how long it lasts and the demographic characteristics of the population of grandparents. The demography of grandparenthood – the timing, length and population characteristics – shape the extent to which young children have grandparents available, how many grandparents are alive and the duration of overlap with grandparents (Leopold and Skopek, 2015a, 2015b; Margolis, 2016). Kin availability is important to understand because it is a necessary condition for having close intergenerational relationships and garnering the benefits that they can offer.

In this chapter, we examine how the demography of grandparenthood varies across 16 countries in Europe and two countries in North America, and why it is changing. These countries represent great variation in contexts with different grandparenting norms, labour-force participation patterns and demographics. Next, we examine variation in two key determinants of intergenerational relationships: the labour-force participation and health of grandparents. Last, we comment on some important changes in the demography of grandparenthood that may occur in the future. To examine changes in these important patterns in the demography of grandparenthood across contexts and over time, we rely on multiple data sources. We use the fourth wave of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) (Börsch-Supan, 2017; Börsch-Supan et al., 2013), the Health and Retirement Study for the United States (2010) and the General Social Survey (2011) in Canada for information about the prevalence and characteristics of grandparents. We also use data from the Human Fertility Database (2017) and the Human Mortality Database (2017) to set the demographic scene for the changes that are occurring.

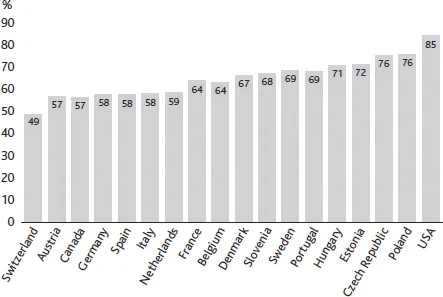

The demographic context of grandparenthood

Not all older adults have or will eventually have grandchildren. How common grandparenthood is among older adults varies greatly across countries. Figure 2.1 shows the percentage of adults aged 50 and above with grandchildren. To construct this, we used the Survey of Health Aging and Retirement in Europe, the General Social Survey in Canada and the Health and Retirement Study (US), including both men and women. Switzerland is the country where the smallest share of older adults has grandchildren, with fewer than half being grandparents (49%). Almost six in ten have grandchildren in Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy and Canada. Being a grandparent is much more common in Northern Europe, with 69% of Swedes, 67% of Danes and more than three quarters of older adults in the East–Central European countries of the Czech Republic and Poland. The United States has the greatest share of grandparents among older adults, with 85% of all older adults in the US having grandchildren.

Figure 2.1: Weighted per cent of adults aged 50 and above with grandchildren, 2010–11

Note: Countries are arranged in ascending order of the per cent of grandparents.

Why is there so much variation in the prevalence of grandparenthood among older adults? Three factors determine this. The first is the age distribution of the population; older populations with higher median ages will, on average, have greater proportions that are grandparents. The second is the level of childlessness, both historical and current, because this determines what proportion of the population cannot become grandparents. This may be because they do not have any children or because all their children are childless. Levels of childlessness vary greatly across contexts. In most European countries, childlessness has been increasing rapidly (Kreyenfeld and Konietzka, 2017). This trend is led by Germany, Switzerland and Austria, where about 20% of women are finishing their reproductive years without children (Sobotka, 2017). England, Wales, the Netherlands and Finland also have relatively high levels of childlessness for recent cohorts (of the 1968 birth cohort, 18% in England and Wales and 17% in the Netherlands, and 20% of the 1967 birth cohort in Finland) (Sobotka, 2017). Although childlessness was quite low until recently in Eastern and Southern Europe, these countries are also seeing steady increases in childlessness. There is divergence within North America. Canada’s childlessness rate reached 20% of the 1965 birth cohort after steadily increasing since the 1946 birth cohort (Human Fertility Database, 2017). However, in the US, after an increase from 10% in 1976 to 20% in 2006, there has been a recent decline to 15% in 2012 (Frejka, 2017).

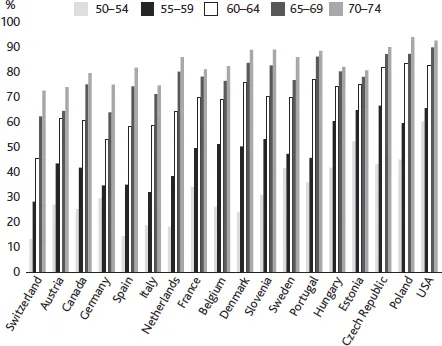

The third factor that influences the share of older adults that are grandparents is the timing of fertility. Fertility postponement over multiple generations has led to grandparenthood occurring later than ever before in North America and Europe. To examine how the transition to grandparenthood happens in middle age in different countries, we turn to Figure 2.2. This figure plots the percentage of men and women combined with grandchildren in five-year age groups, between ages 50 and 74, by country. Countries with a relatively low mean age at first birth generally have greater proportions of older adults who are already grandparents in their early 50s. For example, in the US, the mean age at first birth is relatively low compared to most European countries (26.8 in 2014) and 61% of US adults aged 50–54 have grandchildren. The Eastern European countries also have relatively early childbearing; here, 3–5 in 10 adults aged 50–54 have grandchildren, as do 5–7 in 10 adults aged 55–59. In countries with a higher mean age at first birth, it is less common to have grandchildren before age 60. Central European countries such as Switzerland, Austria and Germany, as well as Canada, have much later transitions to grandparenthood because of later parenthood. As shown in Figure 2.2, fewer than one quarter of adults in Switzerland and Canada aged 50–54 have grandchildren, and the transition in these countries usually happens in the later 50s and 60s.

Figure 2.2: Weighted per cent of adults aged 50–74 with grandchildren, by age group and country

Note: Countries are arranged in ascending order of the per cent of grandparents ages 50 and above.

The length of grandparenthood

The length of grandparenthood is important for contextualising intergenerational relationships because it represents the time available for intergenerational interactions and transfers. Prospective grandparents may want to know their expected time as a grandparent; if they look forward to it, they might make positive health behavioural or lifestyle changes to remain active and alive during this period.

At first glance, the length of grandparenthood is a simple concept. At the individual level, it is the time between the transition to grandparenthood and the respondent’s end of life. However, surveys rarely collect data on the age at which transition to grandparenthood occurs; much more often, they only collect current grandparent status. At the population level, one could create a measure for the average length of grandparenthood for a particular cohort. However, for recent cohorts we would have to wait until mortality is realised for the whole group. Therefore, we can only construct cohort measures of the length of grandparenthood for cohorts that have already died. It is much more useful to draw on demographic measures to get a sense of how the length of grandparenthood is changing over time. Recent research has used the Sullivan (1971) method (Jagger et al., 2006) to estimate the number of remaining years at each age that adults in a population will spend as a grandparent, and also without grandchildren. This measure can be interpreted in the same way as life expectancy at a certain age: if one experienced all the age-specific rates for grandparenthood and mortality, how long on average would someone at a given age in a certain year spend as a grandparent, and how long would someone spend without grandchildren?

How long, on average, is the period of grandparenthood? Estimates for North America are between 19 and 26 years for the years 2010–11. In 2011, the average length of grandparenthood was 24.3 years for Canadian women and 18.9 years for Canadian men (Margolis, 2016), and 25.5 years for US women and 21.5 years for US men (Margolis and Wright, 2017). Within the United States, there is great variation in the average length of grandparenthood by ethnicity. For example, Hispanics have a longer period of grandparenthood than their non-Hispanic Black or non-Hispanic white counterparts due to greater longevity and earlier transition to grandparenthood (Margolis and Wright, 2017). There is much less variation in the length of grandparenthood by education due to greater longevity offsetting later entry into grandparenthood among the highly educated (Margolis and Wright, 2017). These studies estimating the length of grandparenthood at the population level are relatively new; we do not yet have comparable estimates for Europe or other parts of the world.

Labour-force participation and health of grandparents

The extent to which grandparents are available to engage in grandchild care and social activities with grandchildren depends in large part on whether grandparents are engaged in the labour force and their health status (Hank and Buber, 2009). Below, we chart patterns of labour-force participation (Figure 2.3) and health status (Figure 2.4) of grandparents across countries in Europe and North America, drawing on survey data from 2010–11.

Figure 2.3 charts the percentage of adults ages 50–69 with grandchildren who reported working at least part time in the last week. We focused on the age range 50–69 because labour-force participation is, in general, very low for people aged 70 and over; for grandfathers ages 70 and over in most countries, labour-force participation is around 2–3% (not shown).

As is evident from Figure 2.3, for both men and women there is a huge degree of variation in the labour-force participation of grandparents ages 50–69 across countries. In North America, about 55% of grandfathers and 45% of grandmothers are working. Similar figures can be observed in Denmark and Estonia. In Southern Europe and parts of Eastern Europe, labour-force participation for grandparents aged 50–69 is much lower; it reaches its lowest levels in Poland and Italy, where around 10% of grandmothers and 12–15% of grandfathers in this age range are working.

This pattern of results is inversely associated with intensive grandparental childcare across countries. Bordone and colleagues (2017), for example, show that the percentage of grandparents providing childcare on a daily basis is highest in Southern European countries and Poland, characterised by familialism by default (Saraceno and Keck, 2010): a system of low formal childcare provision and meagre parental leave policies. In other European countries, grandparents are usually less intensively involved in grandchild care. Although the direction of causality between family policies, the provision of grandparental childcare and female labour-force participation is hard to establish, the cross-country variation observed in Figure 2.3 may suggest a potential conflict for grandparents between the roles of childcare provider and worker. Previous studies have also hypothesised competition between the two roles and shown that the arrival of the first (or a new) grandchild accelerates retirement (Lumsdaine and Vermeer, 2015; Van Bavel and De Winter, 2013).

The results in Figure 2.3 complement the analysis by Leopold and Skopek (2015b), who used survival methods to estimate the median age of becoming a grandparent and compared it with the median age of retirement for those who ever worked. They found that in bot...