![]()

Chapter 1: The Demographics and Culture of

Dual-Language Learners in the United States

-

Who Are the DLLs in Your Classroom?

English language learners account for 9.5 percent (five million) of US public-school students (US Department of Education, 2019). Do you know the number-one country of birth for ELLs in the United States? Did you guess Mexico? China? If so, guess again—it is the United States. Most ELLs in public schools were born in the United States and are US citizens. In fact, among the children who are ELLs in pre-K through fifth grade, 85 percent were born in the United States, as were 62 percent of ELLs in grades 6–12 were (US Department of Education, 2019). They are the children of first-generation immigrants and have been taught a language other than English by their families.

Another misconception is that ELLs are only in border states, such as California, Arizona, and Texas. Of the student population of California, ELLs make up 20.2 percent; however, the largest growth in the ELL population in recent years has been in the Southeast. For example, in the Fairfax County, Virginia, public school system, more than half the total student population speaks a language other than English at home, including more than 180 different languages and dialects (Fairfaxcounty.gov, n.d.). Other states that account for the majority of ELL students in public schools are Illinois (9.8 percent), Florida (9.2 percent), New York (7.9 percent), and New Jersey (5.2 percent) (Blizzard and Batalova, 2019). In addition, some midwestern states, such as North Dakota at 115 percent, have experienced the largest percentage of growth over the last ten years. Chances are you will have the opportunity to teach ELLs no matter where you live!

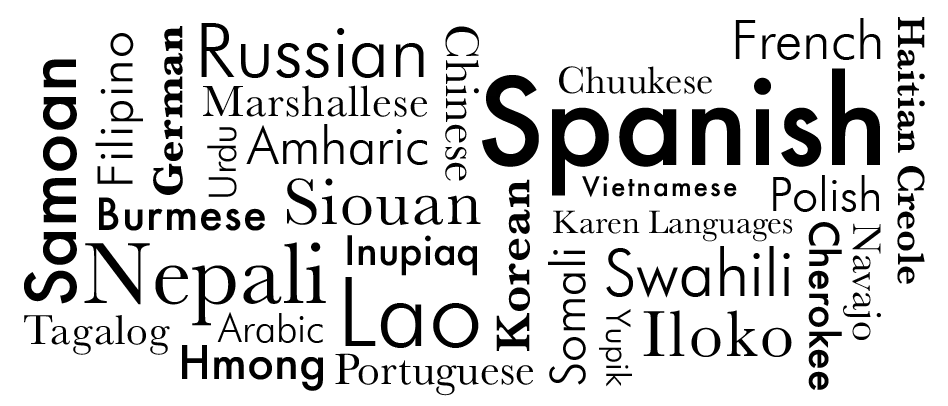

The majority of ELLs in America speak Spanish, followed by speakers of Arabic or Chinese. In fact, ELLs in US classrooms speak more than 160 different languages (Bialik, Scheller, and Walker, 2018). Other common languages include Vietnamese, Somali, Russian, and Hmong (US Department of Education, 2019). Although the majority of ELLs speak Spanish, of those that come from countries other than the United States, not all of them come from Mexico. They come from a wide variety of Central American and Caribbean countries. Thus, the cultural context in which they speak Spanish is very different. This is similar to how people who speak English in the United States differ from those speaking it in the United Kingdom or New Zealand. All these speakers can understand each other; however, there is a layer of culture, vocabulary, and idioms that is not readily comprehensible.

-

-A Word about Generalizations

Even though the majority of ELLs in the United States speak Spanish, a teacher cannot label a student as Hispanic and leave it at that. Spanish speakers come from more than thirty countries around the world, and the United States is actually in the top five countries that are home to Spanish speakers. Argentina, Chile, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Mexico, the Philippines, and Spain all have majority populations that speak Spanish as their L1 (Simons and Fennig, 2017). The Spanish speakers from these countries are culturally very different from each other and should not be labeled together as Hispanic. This thinking also applies to children who come from countries in Asia, such as China, Vietnam, Thailand, or Japan. They should not be lumped together as Asian. In this case, in addition to very different customs, traditions, and geography, they also have different L1s.

Each child is unique, bringing individual experiences, preferences, talents, abilities, and interests. Students can learn English even if they do not completely acculturate into North American culture (Litwin and Smith, 2019). Celebrate each child’s cultural and ethnic background, and look for ways to integrate it into the classroom. This not only complements their education in the classroom, but also gives all students the opportunity to learn more about a wide range of diverse backgrounds.

As educators, it our responsibility get to know the children we work with and to promote an inclusive space for all students. We will look at generalizations in more depth in chapter 4.

![]()

Who Is Immigrating to the United States?

In 2017, only 13.6 percent of the US population was made up of immigrants. Of this number, 77 percent of them immigrated to the United States legally (Radford and Noe-Bustamante, 2019). Additionally, researchers project that by 2055, the number of Asian immigrants will surpass Hispanic immigrants (Pew Research Center, 2015).

In 2018, 27 percent of the people who immigrated to America were from South and East Asia (Pew Research Center, 2015). This is a slightly higher percentage than those from Mexico (25 percent). Table 1.1 will better illustrate the countries of origin of immigrants currently living in the United States as of 2017, which is the most current data available at this time.

-

Languages Spoken by ELLs in the United States

![]()

Understanding Linguistic Enclaves

Many newly arrived immigrants live in linguistic enclaves. A linguistic enclave is an area where there is a concentration of people who speak the same L1 and have either just arrived in the United States or were born to first-generation immigrants and who are learning English and American culture. My parents were from an area of Nebraska where most of the people were descendants of immigrants from Sweden and Denmark. My great-grandmother emigrated at age thirteen in the late 1800s from Denmark and lived in this enclave. She attended a church that worshiped in Danish, and most of the people living around her also spoke Danish. She learned English BICS and became a janitor at the post office. She remained at a BICS level of English until my grandmother started school. She then studied along with my grandmother from elementary school to college and obtained a CALP level of English.

Linguistic enclaves exist in almost every city in North America. For example, there are large Ethiopian populations in Los Angeles, California (Banach, 2005) and Seattle, Washington (Hinchliff, 2010). Many people of Somali descent live in Minneapolis, Minnesota. People from El Salvador have settled in Raleigh, Charlotte, and Greensboro, North Carolina in addition to the large metropolitan areas of Los Angeles and Washington, DC. In a large city near me, several generations ago, most of the residents of one section of the city were recent immigrants from Italy and spoke only Italian. Remnants of this linguistic enclave still exist in the form of well-established Italian restaurants, an Italian festival every spring, and a bocce court open to the community. You probably have a linguistic enclave near you, too. As you’ll learn in the next few chapters, living in a linguistic enclave will strengthen a child’s first language, thus strengthening their future level and competence in English.

![]()

It’s Not Just about Language, It’s about Culture, Too

Along with a language other than English, young ELLs come to school with rich and diverse cultural backgrounds. Keep in mind that children who speak the same language may not have the same cultural experiences. In fact, children speaking the same L1 can have very different cultures, just as a child from Alaska has a different culture and experience of America than a child from Florida. Although both children may speak English and be familiar with SpongeBob or Elmo or all the lyrics to the Frozen soundtrack, they likely have different cultures and experiences around traditions, climate, idiomatic language, clothing, and some food choices. Similarly, a child from Mexico and a child from El Salvador have had different experiences with traditions, foods, clothing, and idiomatic language.

In addition, children who come to America may have had experience with school but may not understand the nuances of American schools. Or a child may never have attended a formal early childhood school setting, or her native classroom setting may be very different from her new school. The food she encounters in her new school may be strange and unfamiliar. That being said, the child knows many things about where she is from that her new teacher and peers do not. A child does not come to school as an empty bucket to be filled but as person full of knowledge and language. The teacher needs to connect to what the child knows and help her to grow and understand the new customs and culture of her American school.

-

At an American elementary school serving a large population of ELLs from a country in Central America, the custodians complained that the children were leaving used toilet paper in piles on the floor beside the toilets. Luckily, one of the pre-K teachers at this school had traveled to this particula...