![]()

1

Ethnicity, capital and the architecture of mobile hopes and dreams

To the degree that identity has come to rest, at once, on ascription and choice, conviction and ambiguity, ineffability and self-management, it has embedded itself in a human subject increasingly seen, and experienced from within, as entrepreneurial. Not least in enacting her or his otherness.

(Comaroff and Comaroff, 2009: 50)

In the late 1600s, Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza argued that we should recognize that affect is crucial to our capacity to act. For him, a central dimension of humanness is the importance that the ‘capacity to be affected’ has for our ability to act meaningfully in this world. One of Spinoza’s concerns was to uncover the work that fear and joy do in mobilizing political subjectivities, a focus that makes his work timely and evergreen. For our purposes, he evokes a fundamental premise – affect is a constitutive rather than a derivative quality in political practice, that is to say, the ways people actually feel is indispensable in the (re)constitution of the social body (Ruddick, 2010: 24). Applied to our interest in populations in the GMS, this means that the potential to improve one’s life (the object of so much development machinery) cannot and should not be separated from an emotional engagement in the process. The capacity to aspire to, or desire for, something better is central to making appropriate and/or opportunistic choices that change one’s life. Or, in the terms I am using to frame this perspective, to understand development and its contingent impacts, material and intimate economies should be conceived as indivisible.

Spinoza distinguishes potentia – an innate capacity to act – from potestas, a top-down control of knowledge that dominates and alienates its audience. Potentia or empowerment is achieved through the social nature of becoming active, where emotions are understood and inform communal action rather than the prescriptive frameworks (potesta) that encourage passive observance of the rules (ibid: 26). Three hundred years later this is eerily familiar to key tenets derived from recent decades of development programmes – participation of local communities is essential, top-down delivery is anathema to sustainable outcomes. But there is more to this picture. According to Spinoza, in order to mobilize potentia, the capacity to act must emerge from a complex interplay of affect and reason which,

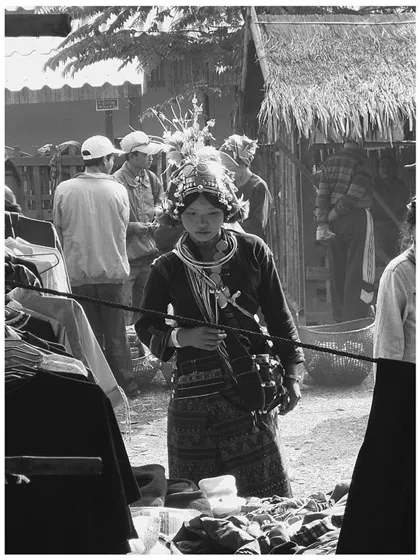

Figure 1.1 Akha woman musing at a monthly market

in turn, entails collaboration with others. “These collaborations,” Ruddick summarizes, “stem from our desire to reproduce ‘joyful’ encounters and avoid painful or discomforting ones” (ibid). Passive engagement of the emotions causes ‘inadequate ideas’ and thereby limits the capacity to act. On the other hand, active engagement creates a sense of accomplishment (joy) through positive collaborations and achievements. This brings us back to the crucial point that Spinoza recognized so many years ago – affective practices are central to the unfolding of modernization and social mobilization processes. Or in the catchphrase of legions of neo-Spinozists: ‘You can’t have effect without affect.’ In this chapter we move beyond a narrow focus on joyous engagement to lay the geographic and conceptual groundwork necessary to profile the ways that aspirations and other sentiments, such as fear and envy, longings and satisfactions, are part of shared affective economies circulating throughout the GMS (and beyond).

The geographic field of our enquiry into these economies was given official definition in 1992, when six Asian countries entered into a (literally) groundbreaking programme of cooperation and development. The agreements created a new entity, the Greater Mekong Sub-region (GMS), transposed over prior cartography in order to highlight its geopolitical importance. Its strategic goal is to revitalize Asian regionalism. Its collective target is more than 300 million people living in countries linked by the Mekong River: Cambodia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic (forthwith Laos), Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam as well as Yunnan Province and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China. Based around billions of dollars invested in infrastructure, growth policies plan to use abundant natural wealth – timber, minerals, coal and petroleum, hydropower – to boost local economies. They also intend to embed more open, market-based systems to create a competitive bloc in an area more recently familiar with war, strife and political conflict. The transition from widespread subsistence farming to diversified supply chain production is regarded as crucial for reducing economic disparities and developing the region’s human capital, even as its actual implementation is far from straightforward.

Market penetration is not new, but it has been given huge impetus under the GMS framework. Given the scale of interventions across this terrain, in particular in the agriculture sector (where resettlement, cash-cropping and contract farming have been furiously leveraged), the first two decades of GMS programming have delivered profound impacts on everyday life. Some people have benefitted as economies have indeed grown noticeably across the region. So too, there are many who might not consider their lives improved as “‘pre-capitalist’ agricultural workers are not only dispossessed and transformed into wage workers, but most often pushed into motion spatially. These displaced workers have commonly migrated across regional divides to relatively urban centres in Thailand and Vietnam, swelling the ranks of the informal and precarious labour markets” (MMN, 2013: 167). For others, perhaps even the majority, sorting out a livelihood remains a fraught mix of imposed interests intermeshed with insistent aspirations. Everyday lives are simultaneously supported and/or shoehorned by policy directives and infrastructure roll-outs in often incongruous ways, in the course of which hopes and dreams end up deployed in a vast range of directions. This is the nature of development’s pointillist canvas– die-hard optimism sitting awkwardly next to life-sap-ping exploitation – details obscured if we rely only on soft-focus. Closer scrutiny shows that, one way or another, development programmes and policy mandates continue to transform lifestyles and landscapes in the GMS in often contradictory ways, as mobility becomes routine and new states of being take centre-stage.

Fields of dreams

Creating economic corridors was earmarked as ‘the first strategic thrust’ of the GMS programme that, substantially supported by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), began in earnest in the early 2000s. Indeed, newly upgraded highways and feeder roads have greatly improved ‘physical connectivity’ and facilitated cross-border trade, investment and labour migration. In so doing, national polities are physically stitched together with a new architecture that continues to transform local livelihoods and diverse aspects of everyday life. In terms of regional planning, priority has been given to ‘clearing the way’ through concrete infrastructure. The ‘software’ aspects of development, that is, how people will actually use the roads, comes in their wake (ADB, 2007: vii). The ADB’s emphasis on first laying roads might well remind one of a phrase from a movie. It’s about a vision; one might say a vision for development through concrete transformation. In the Hollywood version, Kevin Costner has a revelation – a baseball field will bring life back to his rural community. “If you build it, he will come” he hears in a dream. Shoeless Jackson, that is. He does come, back from the past to create a new future and so too do people – in the final shot we see an endless stream of cars snaking down the highway through the evening dusk on their way to the field. Brought together by the building of this diamond, turning what was cornfields into an icon of American culture. They came to watch the baseball just as they came to watch the movie. Field of Dreams was a big-time commercial hit.

Cut back to the GMS where big-time dreams are also common currency. A glossy brochure released in 2004 touted the wonders of Golden Boten City to be carved out of remote forest flanking the Northern Economic Corridor just inside the Lao border with China. The Chinese/English text trades in the language of fantasy as heavily as any Hollywood scriptwriter. After listing the preferential state policies it enjoys to promote import, export and opulent entertainment, this free-trade zone is wishfully described as: “The promised land for freedom and development, wide-world for adventure and fortune. A place where: elite and wisdom [sic], luxury and desire, legend and dream, mystery and fact, all go beyond your imagination.” In fact, the investors were seriously hoping the business men and women they attract could very concretely imagine the benefits as they spend 48 pages in this brochure telling of wonderments to be established in Golden Boten City. It, too, might have been subtitled “Field of Dreams” (although, as we will see, happy endings are not guaranteed).

The Upper Mekong is a previously remote area that has often been the subject of ambitious, albeit unrealized, dreams of regional integration. Take, for example, the nineteenth-century British and French missions in search of land-based trade routes to link mainland Southeast Asia with China. So too, cross-border links have at times been etched by spiritual rather than economic mapping. Cohen (1999) describes transnational Buddhist revivalist yearnings inspired by the charismatic and peripatetic monk Khruba Bunchum, who in the 1990s carved a sacred cartography through reliquary-building tours along routes that are remarkably homologous with roads subsequently constructed by the GMS programme. By the early twenty-first century, concrete freeways have become the more prominent symbol of utopian visions as the GMS programme has built corridors for traders, truckers and tourists to move rapidly through previously remote and hinterland areas of neighbouring states (see Figure 0.1 on page 12). Connecting highways and ring-roads linking the six GMS countries are core elements of visions of regional economic cooperation. Border points have been upgraded, customs protocols streamlined and border towns are booming. Bridges have been built, airports with international runways established and troublesome rapids in the Mekong exploded so large cargo boats from China can run unimpeded. Same premise as the movie – in this case plural: “If you build it, they will come.” Provide thoroughfares and people will come together to experiment with, or exploit, newfound opportunities. Of course, roads and infrastructure development are about more than just people movement. They also envisage other types of mobility: goods and ideas, trade and commerce. But the notion of integration via these corridors relies most fundamentally on people interacting with people. Roads are magnets as well as thoroughfares. Despite being about movement they are also about openings, about connections, about opportunities, about new forms of economic and social engagement. For thousands – perhaps millions – they represent new choices due to the passage they provide. People come to roads as much as they move along them. And people connect in any number of social and commerce-related interactions, from the clinical handshake over a cultivation contract through to a sexually intimate sojourn with a village woman all in the name of economic integration. Invited, not in this instance by a Hollywood icon, but instead an equally global symbol of modernization – a gleaming blacktop, a new asphalt artery called in tabloid fashion a ‘new economic corridor’ – that is, in similar fashion, transforming lives.

Befitting this vision, it is not just investment brochures that trade in optimistic rhetoric. The ADB GMS website intones “The rich human and natural resource endowments of the Mekong region have made it a new frontier of Asian economic growth. Indeed, the Mekong region has the potential to be one of the world’s fastest growing areas.” 1 Bringing such projections into a practical scale of management, the GMS has become a high profile development zone fuelled by donors busily advocating the requisite buzzwords: connectedness, competitiveness and community. Hopes that these manoeuvres will be synonymous with rapid livelihood improvement take root at all levels: from the high-story policy think-tanks prophesying competitive advantage through to hand-in-the-dirt subsistence farmers wondering precisely what they might compete with as market economies become the chief mainstay of everyday social relations. What is far less clear is what it means for the many millions of poor people to become ‘connected’ in a subjective sense within this contrasting political, economic, cultural and geographic terrain. As mentioned, the scale of impetus to change people’s lives in this region is huge, stemming from massive funds soaked into numerous hardware

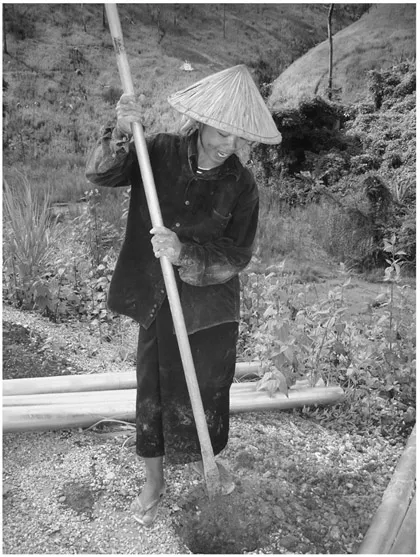

Figure 1.2 Local labour on the Northern Economic Corridor

schemes geared to assisting in market diversity. But while ‘community’ is seen as a logical alliance based on cultural proximity and shared programme goals, a closer look at the region shows a more complex reality. At one level, the spread of market capitalism has been pronounced and profound in its reach into even the most remote parts of the GMS where technology as the conduit of commodity desire and wage labour as the conduit of capital have become part of daily life in ways unimaginable a decade or two ago. At another level, the region is fraught with ambiguities inherent in the shift to new economic sensibilities. Jean and John Comaroff, so precise at pointing out paradoxes within global workings, write that neoliberalism:

appears both to include and to marginalize in unanticipated ways; to produce desire and expectation on a global scale, yet to decrease the certainty of work or the security of persons; … above all, to offer up vast, almost instantaneous riches to those who master its spectral technologies – and, simultaneously, to threaten the very existence of those who don’t.

(Comaroff and Comaroff, 2001: 8)

It is exactly this ambivalent mosaic of everyday life that the roads cutting through the mountains or crossing borders at new checkpoints complicate in both material and immaterial ways. Even as they streamline the physical topography and bisect national cartography, they introduce peaks, troughs and crossings of an altered social landscape: new opportunities, new pitfalls, new projects of self-making, new threats to wellbeing.

Ethnic intersections: time-worn and heartfelt

Although the GMS countries, except the two Chinese provinces, belong to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and share in the goal of collectively orchestrated policies, there is little in the way of recent history that guarantees any sense of cultural or political uniformity for regional plans. The slogans promoting community and connectivity paint over a vast canvas of economic and cultural variation. The GMS encompasses the financial powerhouses of Yunnan and Thailand, the rapidly growing economy of Vietnam alongside the improving but less stellar performers of Laos and Cambodia and the recently unshackled resource-rich but opportunity-starved Myanmar. It is politically diverse: the past 50 years have seen bloody confrontations and sometimes horrifically damaging attempts at different modes of governance from uneven command economies, isolationist autarky, dictatorship and haphazard democracy.

Nowadays, liberalized trade policies have earmarked a newfound commitment to minimally fettered market relations even as the wide variability in human, social and environmental resources means this integration will play itself out in uneven ways for years to come. Future uncertainties notwithstanding, this book is not about the bumpy trajectory facing regional economic growth per se. Rather it is about how the attempts to build both physical and symbolic roadmaps may well deliver economic corridors, but that these concrete tarmacs are emblematic of a far more profound set of changes. That is to say, how people use opportunities in ways that both embrace and exploit the increased range of social interactions available to them is uncharted and unpredictable. And yet, how sentiments implicit in capitalist social formations – the heady aspirations and the dehumanizing realities – are, in fact, given substance within and beyond ethnic bounds is central to the way change is unfurling in the GMS.

One fact is obvious: both the concrete roads and ephemeral visions of progress in the GMS embrace a vast mixture of peoples and cultures that defies ready assimilation into neat blueprints. The region is populated by ethnic groups with different ways of being and thinking that prompt complex and sometimes ambiguous relations between politicized bodies at the macro level and contradictory and sometimes ambivalent interpersonal relations at the micro level. In the past, divergent aspirations have led to some groups seeking active distance from state-led modes of governance and socio-economic integration. Hence James Scott’s (2009) assertion that millions, who historically lived in stateless societies in Zomia (a putative region covering mainland Southeast Asia), managed to avoid assimilation into larger lowland polities by strategic withdrawal and geographic dispersal into the mountains. Core residences of Zomia’s disparate ‘state-avoiding’ populations were the cool hills that flank the adjoining border areas of Lao PDR, Thailand, Southern China, Myanmar and Vietnam – also called the Southeast Asian Massif. These days the GMS (adding Guangxi to the mix) is home to roughly 65 million people from ethnic minority groups. But, as Table 1.1 makes abundantly clear, even today physical dispersal and social distance mean accurate headcounts are hard to come by.

What is more clear-cut is that a large percent of the lowland rice-growing peoples in the GMS belong to the Tai-language group born of a thousand-year diaspora heading south from China and forming a cultural area “comparable in some respects to say that of the romance languages in Europe” (Turton, 2000: 3). This cultural collectivity is easier to count as it comprises majority national populations (ethnic Thai in Thailand, Lao in Laos), regionally dominant populations within national boundaries (Shan or Tai-Yai in Myanmar) and considerable sub-populations (Dai in China and Tai in Vietnam). For many centuries, Tai populations have distinguished themselves by etching idioms of backwardness, primitiveness and ethnic inferiority to distinguish non-Tai groups. The extent to which Scott’s survival strategy treatise characterizes the historical cut and thrust of state/non-state relations is still debated. What is less contentious is that a longstanding dichotomy in Southeast Asia – minority/majority, lowland/highland, people that belong/ people that don’t – has endured as a structuring device governing social, economic and political relations between different ethnic groups. “Since time immemorial,” as Formoso (2010: 320) puts it, “lowland rice growing peasants have despised ‘tribesmen’ living in nearby hills. But at the same time as they negated their cultural existence, while their rulers attempted to assimilate these backward peoples, they were pragmatic enough to take advantage of their economic resources and of their situ...