1.2 Cultural diversity or globalized markets?

Cultural diversity has emerged as a key concern at the turn of a new century…. Some see cultural diversity as inherently positive, insofar as it points to a sharing of the wealth embodied in each of the world’s cultures and, accordingly, to the links uniting us all in processes of exchange and dialogue. For others, cultural differences are what cause us to lose sight of our common humanity and are therefore at the root of numerous conflicts. This second diagnosis is today all the more plausible since globalization has increased the points of interaction and friction between cultures, giving rise to identity-linked tensions, withdrawals and claims, particularly of a religious nature, which can become potential sources of dispute.

(Introduction to the 2nd UNESCO World Report, 2009a)

As this is a book on ethnic marketing, the nexus between cultural diversity as used by UNESCO, and ethnic diversity needs to be established. Its Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity (UNESCO, 2002) reaffirmed that ‘culture should be regarded as the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of society or a social group, and that it encompasses, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs’. In its specification of societies and social groups, UNESCO focused on those linked by social identity with commonalities closely akin to ethnic groups (see section 1.3), rather than by national culture. UNESCO (2009b) noted a past tendency to equate cultural diversity with the diversity of national cultures, but distinguished the two by the different sources involved in identity creation with the former often deriving from multiple sources.

In contrast with the one country–one culture paradigm, virtually all countries contain cultural diversity to varying degrees, within their national boundaries. This is an important observation because businesses may fail to recognize that they operate in an environment of cultural diversity where different indigenous as well as migrant ethnic groups can be expected to affect the demand for, and supply of service-products. Recognition that many subcultures may make up potentially important market segments can lead to businesses often designing service-products and marketing programs tailored to their needs (Kotler et al., 1998). In some cases, provided a high degree of homogeneity exists between consumer groups defined by the ethnicity of their members, their aggregation may also be advantageous for particular marketing purposes.

There are a few countries in the world that are ethnically homogenous, but they are a very small number and they’re shrinking. You have Korea, you have Japan, and I’m at a loss really to come up with another one after that. The reality is that almost all the other countries in the world, be they developed economies or developing economies, are extremely ethnically diverse, at least in the big cities.

New York City has always been an ethnically diverse city–also Paris, London, England. That diversity is being replicated in the secondary cities of other countries and, increasingly, into the countryside, slowly adding a lot more to ethnic mixing. So, it becomes a lot more difficult to describe an ethnicity from any pure perspective, where you have an untouched group that has not been influenced by other groups. I mean, it was never true to begin with. Our cultures have always had to adapt aspects from other cultures. It’s an organic thing. It’s something that evolves over time. But in today’s world, it’s difficult to find individuals that are solely compartmentalized into one particular ethnic group.

Mark Cleveland

In the Japanese case, there is a general believe belief that the Japanese population is homogeneous, but that is not correct. There are many Koreans, many Chinese and some people from Brazil. They created communities in many places in the Japanese main islands.

Ikuo Takahashi

The global process by which capitalism, global transport, industrialisation, urbanisation, mass communications and transnational cosmopolitanism have been transforming society, underpins a view of the inevitable dissolution of boundaries across national cultures and of the demise of the social and political importance of ethnicity, and consequently, its relevance for marketing (Cleveland and Laroche, 2007; Hutchinson and Smith, 1996). The predicted ultimate outcome of this global process is a homogeneous global consumer culture. The interview with Cleveland (this text) provides insights into this philosophical position.

Expectations of the dwindling importance of ethnicity as a social force differ from predictions that the use of ethnicity as a criterion for segmenting markets will continue to increase in importance (Stratton and Ang, 1998; O’Guinn, Imperia and MacAdams, 1987). This is consistent with the view that ‘globalisation has precipitated identity construction on an unprecedented scale’ that has reinvigorated ethnicity (Cornell and Hartmann, 1998: 250), such that cultural diversity has become a major social concern, linked to the growing diversity of social codes within and between societies, with cultural roots running deep and often lying beyond the reach of exogenous influences (UNESCO, 2009b). As argued by Kanbur, Rajaram and Varshney (2011), ‘If ethnic division causes conflict, conflict sharpens ethnic division’ (p. 151).

A major implication of the contradictions created through globalisation is that strong ethnic identities are locally constructed, arising from the situations groups and individuals deal with every day. This local construction casts doubt on the usefulness of targeting transnational ethnic segments, as called for by Usunier and Lee (2014), or the global homogenized segments discussed by Cleveland, Laroche and Papadopoulos (2009), as well as the unqualified transferring of a domestic marketing strategy (marketing to Koreans in Korea) to a wider international context (the Korean ethnic group residing in Japan), or of using an ethnic marketing strategy (marketing to the French ethnic group residing in Brazil) for cross-cultural marketing purposes (Brazilian organisations marketing to the French people in France).

Cultural or ethnic diversity within nations is difficult to measure, particularly using single demographic indicators such as a resident’s country of birth, first language spoken, or race. For example, The World Factbook, 2013–2014 (Central Intelligence Agency, 2013) under its field listing for Ethnic Groups in each country lists Australia as White, 92 per cent; Asian, 7 per cent and Aboriginal and Other, 1 per cent; primarily a crude racial, sometimes tribal division which in this case grossly oversimplifies but in the description of ethnic groups in countries such as Malaysia and Russia, provides a closer approximation. Nevertheless, because of the dearth of measurement pertaining to a person’s self-ascribed ethnicity within the national borders of most nation-states, single demographic measures are often used. On this basis within the European Union (EU), there were 10 countries hosting over 5 per cent of nonnationals in the total population, six of which hosted 10 per cent or more–namely, Luxembourg, Czech Republic, Latvia, Estonia, Spain and Austria (European Commission, 2011).

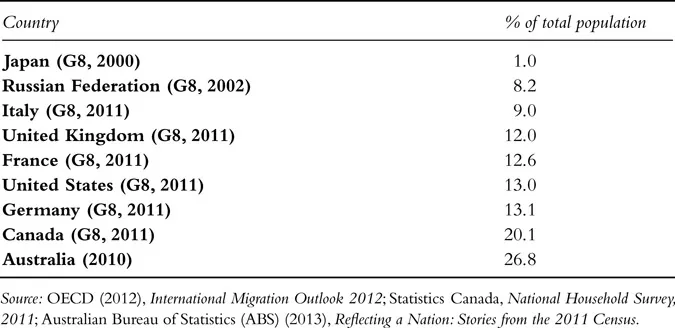

TABLE 1.1 Proportion of foreign-born population in the total population, Australia and G8 countries

The foreign-born populations in the G8 countries and in Australia, shown in Table 1.1, reflect large, migrant populations likely to have diverse ethnic backgrounds. One out of five people in Canada’s population is foreign-born, the same ratio applying when visible minority criteria is applied (by self-ascription). In both cases, the main source of immigrants is Asia (including the Middle East). South Asia is the major source for visible minorities (Statistics Canada, 2013).

Australia, with the highest ratio, may be an underestimate since 1.6 million Australians did not state their birthplace or their parent’s birthplace in the 2011 Census. Reflecting self-ascription to the cultural group of closer association, over 300 ancestries were separately identified in that Census, the major ones being English (36 per cent) and Australian (35 per cent). The majority of people reporting an Australian or European ancestry were born in Australia (for example, only 10 per cent of people reporting a German ancestry were born in Germany). The pattern differed for those reporting Asian ancestry (for the Chinese, 36 per cent were born in China, 26 per cent born in Australia and 38 per cent born elsewhere [ABS, 2013]).

The inadequacy of measures such as nonnational and foreign-born residents to effectively capture the magnitude of ethnic diversity within many countries is starkly reflected in Spain, a nation-state with centuries of common history but still marked by regions seeking to express their ethnic identity through the pursuit of greater autonomy or independence (The Economist, 2014; Edles, 1999). Outside of Europe, states such as Malaysia and South Africa have maintained their ethnic diversity, based on migration flows many generations past (Lai, Chong, Sia and Ooi, 2010). In short, ethnic diversity will often be much greater than that reflected by simple demographic indicators but it is a starting point.

The diverse nature of nations is also reflected in the evidence formed from research on many specific minority ethnic groups (discussed in chapter 6) and on many reports of the cultural diversity of cities (rather than countries), including the attribution of awards to recognize culturally diverse cities (NLC, 2014). Arguably, it may be difficult to identify a major city in OECD countries that is not culturally diverse (Price and Benton-Short, 2007), although the cultural make-up cannot be expected to be the same (...