![]()

Introduction

Peter Fredman* & Liisa Tyrväinen**

*Mid-Sweden University and European Tourism Research Institute (ETOUR), Östersund, Sweden, and **Finish Forest Research Institute (METLA), Vantaa, Finland and University of Lapland, Rovaniemi, Finland

Nature has been a key attraction factor for tourism in the Nordic countries for decades. The demand for nature-based tourism has steadily grown and is the most rapidly expanding sector within tourism across Europe and elsewhere (Bell et al., 2008; UNWTO, 2009). This demand has created opportunities for nature-based tourism to develop as an economic diversification tool within regions rich in natural amenities such as northern Europe. In Finnish Lapland, for example, tourism is already the most important economic sector providing more job opportunities than the forest industry (Council of Lapland, 2008). Nature-based tourism is also a growing land-use activity and economic sector involving different types of entrepreneurs, many of which are relatively small, located in rural regions and may only work parttime in tourism combined with agriculture, forestry or other rural means of livelihood. Many of these businesses are also challenged by seasonality in tourism demand and conflicts with other natural resource uses.

But nature-based tourism is not only about tourism businesses and tourists visiting nature. The natural environment as a basis for tourism involves many challenges related to communities and the management of natural resources. As such, landowners, management agencies, other resource users (e.g. forestry, agriculture, fisheries) and nature protection organizations also become an important part in the supply of nature-based tourism opportunities. In many cases, decisions on natural resource use feature public good considerations and are mostly beyond the control of the private tourism industry. In the Nordic countries the state is a key landowner besides local municipalities, which provide most of the protected or other nature areas with infrastructures for outdoor recreation and tourism provision. And such areas may function as attractions in the tourism system (Wall Reinius & Fredman, 2007).

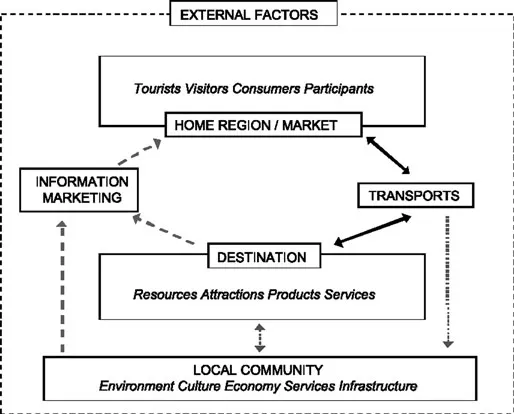

Figure 1 is a basic model of tourism used to illustrate the principles and operation of the nature-based tourism system. First, looking at the demand, nature tourists are visitors to nature areas, often as participants in various forms of activities (e.g., hiking, skiing, swimming, boating) and as consumers of commodities. Since tourism by definition involves travel away from home, the home region of the tourists is also the target market. Looking at the supply side of the system, fundamental to the nature-based tourism destination are natural resources (e.g. mountains, lakes, rivers, forests, beaches) attractive enough to be significant pull factors to trigger travel. Access and attractiveness of these resources are often supported by products and services provided by private tourism providers, public agencies and land owners (e.g. accommodation, visitor centres, guides, trails). In nature-based tourism, the local community is often highly integrated with the tourism supply at the destination. Natural resources used by tourists are a subset of the natural environment of the local community, which are often highly integrated with local traditions and culture. The presence of service and infrastructure (e.g. shops, outfitters, parking, local public transportation) define the tourism supply and affect how visitor spending contributes to local economic impacts. As for all types of tourism, there is a need for transportation systems to get people to the destination, for the local community to have strong incentives to provide information, and to do marketing to attract more visitors and increase sales. Many small entrepreneurs are working in remote rural areas and are encouraged to use (or try to use) networks in marketing and cooperatively provide the services together. Finally, the nature-based tourism system is affected by a multitude of external factors such as rules and regulations (e.g. right of access, environmental protection), other competing resource uses (e.g. forestry, fishery, farming), climate change, economic recessions and safety. From Figure 1, it becomes apparent that nature-based tourism is characterized by having many stakeholders – not just those traditionally involved in tourism, but also those associated with the protection, management and utilization of natural resources.

Figure 1. Principles of the nature-based tourism system.

Nature-based tourism in the Nordic region is framed and strongly flavoured by specific socio-economic and environmental features of each respective country. There are of course large variations between the agricultural parts of southern Sweden and Denmark compared to the large forest lands of the interior north and the mountainous arctic of Sweden, Norway and Iceland. We can, however, observe some characteristics valid for large parts of this region. Firstly, there are large amounts of rural and peripheral areas with decreasing amounts of job opportunities and population numbers. Secondly, there is an increasing rate of urban population with a high standard of living demanding recreation opportunities in the proximity of the cities, but also in the countryside. Thirdly, several of the Nordic countries have a high proportion of forest land (up to 69%) intensively used for timber production, particularly in Finland and Sweden. Fourth, there is a large number of private landowners making resource use decisions according to their own multi-objective ownership motives that may discourage tourism use. In contrast to many other countries where nature-based tourism often takes place in designated areas (e.g. National Parks or protected areas), in Finland, Norway and Sweden the Right of Public Access allows access for recreation and traditional use of nature including berry picking and mushroom collecting (Emmelin et al., 2010; Fredman & Sandell, 2009). These rights are often considered of the utmost importance by the general public and they cause both challenges and opportunities to nature-based tourism business operators.

Defining Nature-Based Tourism

One of the fundamental problems in studying nature-based tourism is in defining both the consumers and the producers within its fairly complex system. Based on a thorough review of the literature, no scientifically defined and universally agreed on definition for nature-based tourism was found. One of the reasons for the lack of a consistent definition is that from a national perspective, it is difficult to separate tourists from outdoor recreationists, or the specific activity from the broader services associated with that activity. For national research purposes, for example in Finland, nature-based tourism has been defined to cover activities that people do while on holiday and which focus on engagement with nature and usually includes an overnight stay (Silvennoinen & Tyrväinen, 2001). Typically this means travelling to and staying overnight in locations close to protected areas, forests, lakes or the sea or the countryside and participating in activities compatible with the location’s natural qualities. While studying the supply side, the key problem is the difficulty of getting information specifically from nature-based tourism entrepreneurs as they are not classified as a separate category or a statistical unit within national or regional statistics. Moreover, assessing the economic benefits from tourism is also difficult as the benefits are scattered in various economic fields such as transportation, restaurant and accommodation services (Huhtala et al., 2010; Tyrväinen et al., 2008). Although it is the natural features that attract people to participate in nature-based tourism, in practice the largest share of the economic impact is generated through traditional tourism services such as travel, lodging and food while nature experiences directly generate less money.

Having said this, however, looking into the wider scientific literature a multiplicity of descriptions of nature-based tourism are presented (e.g. Dowling, 2001; Hall & Boyd, 2005; Laarman & Durst, 1987; Lang & O’Leary, 1997; Mehmetoglu, 2007; Müller, 2008; Valentine, 1992). These scientific definitions often include environmental awareness or nature conservation motives as an inherent target while in practise, less sustainable practices such as motorized activities are often among the services offered to clients. Using motorized vehicles as part of a product to more easily reach the sites within the tourism destination is common today and motorized safaris (e.g. snowmobiling) often bring economic income to entrepreneurs. In spite of the positive image of the term nature-based tourism, it need not necessarily be sustainable, although it is an important goal to strive for both in theory and practice. Looking at nature-based tourism from a sustainability perspective will inevitably take us to the concept of ecotourism, which can be seen as a normative sub-category of nature-based tourism. The concept of ecotourism is heavily studied and after much debate, some sort of definitional consensus in the literature has been reached. For example, Donohoe and Needham (2006) reviewed 42 definitions and concluded that ecotourism is characterized as nature-based, preservative, educative, sustainable, responsible and ethical tourism. It addition to the nature-based component, these are all normative features guiding us how ecotourism should be performed. Taking the lessons learned from ecotourism, in terms of nature-based tourism, most of us inherently have an image about what it is, but no one has really told us what it should be.

In Finland, the definitions used in policy documents and scientific work have tried to capture the current practices within nature-based tourism and at the same time bring in the demand for sustainability in developing the sector (Hetemäki et al., 2006; Koivula & Saastamoinen, 2005). Tyrväinen and Tuulentie (2009) discussed the nature-based tourism definitions used in Finland and concluded that nature can have various roles depending on the client’s needs, expectations and motives. The nature experiences offered within program services may contain motorized or non-motorized activities and include various types of natural environments, often combined with knowledge of local cultures. The general trend until now has been to relatively openly accept various features within the economic sector (including non-motorized activities) to fully involve the different stakeholders in policy discussions. One of the key objectives, however, is to improve sustainability of the nature-based tourism services together with the key actors. A pioneering example of this is a set of guidelines from 2004 of how sustainable nature-based tourism is promoted in national parks and protected areas in Finland (Högmander & Leivo, 2004).

We believe that most scholars interpret that nature-based tourism is associated with leisure activities taking place in nature areas, and that key components are the visitor (being away from home) and experiences of, or in, nature. In an international review of nature-based tourism definitions and statistics, Fredman et al. (2009) identify four recurrent themes; (i) visitors to a nature area, (ii) experiences of a natural environment, (iii) participation in an activity, and (iv) normative components related to e.g. sustainable development and local impacts. The human nature nexus was elaborated by Valentine (1992) who proposed three types of relationships – experiences dependent on nature (e.g. safari), experiences enhanced by nature (e.g. camping), and experiences where nature has a subordinate role (outdoor swimming pool). Intensity, social context and duration are additional factors affecting the experience of nature. A similar approach was elaborated by Karlsson (1994) who studied the relationship to nature among nature-based tourism entrepreneurs using two dimensions: (i) focus on nature and (ii) nature as arena (degree of authenticity). He argues that three of the four possible combinations of these two dimensions define nature-based tourism – the only one not considered nature-based tourism is when tourism does not have a nature focus and does not take place in an authentic nature environment (e.g. urban area or indoor). Fredman et al. (2009; pp. 24–25) proposed a minimalistic definition based on the official Swedish definition of tourism for methodological consistency and comparability with other sectors of the economy (cf. Blamey, 1997): “Nature-based tourism is human activities occurring when visiting nature areas outside the person’s ordinary neighbourhood”. From this then follows that “the nature-based tourism industry represents those activities in different sectors directed to meet the demand of nature tourists”.

The advantage of such a definition is that it connects to other types of tourism and there is a high degree of flexibility to identify sub-categories of nature-based tourism. There are, however, still some critical issues to be solved regarding what activities should count and what is a nature area. Depending on purpose and context, nature-based tourism can then be sub-categorized into form (domestic, international), when (leisure, work), motive (e.g. nature, social, physical), activity (e.g. consumptive, nonconsumptive), where (nature types or regions), and how (e.g. organized, commercial, sustainable, motorized, artificial).

The examples above illustrate how nature-based tourism has been elaborated rather than defined in the tourism literature. However, if nature-based tourism is to be considered an identifiable sector in the national and regional economies it needs to be measured, and measurements require a definition. Defining nature-based tourism will not just help the estimation of the magnitude of the industry, it will help reduce conflicts with other resource users, identify market segments, contribute to a more sustainable development and monitor changes over time. In addition to the topics raised above, we also stress the importance of systematic measurements of nature-based tourism across different countries, including vertical integration of European, national and local levels (Sievänen et al., 2008; Yuan & Fredman, 2008).

Researching Nature-Based Tourism

The tourism literature provides ample support for the significance of nature-based tourism, often considered to grow faster than the tourism industry in general (Buckley, 2003; Fallon, 2000; Hall & Boyd, 2005; Mehmetoglu, 2007; Newsome et al., 2002; Page & Dowling, 2002). According to the World Tourism Organization, approximately 10–20% of all international travel is related to nature experiences (www.unwto.org). The share of nature tourists is, however, larger in northern Europe. The National Tourism Board of Finland estimates that a third of all foreign tourists participate in nature activities (MEK, 2009).

Looking at the demand side of nature-based tourism in North America, there are arguments for a shift away from nature-based recreation (e.g. Pergams & Zaradic, 2006, 2008), while others claim the opposite trend (e.g. Cordell, 2008). A study of the number of visitors to 280 protected areas in 20 countries show increases for most countries, except the USA and Japan (Balmford et al., 2009). Other observations indicate that nature-based recreation is increasingly becoming specialized, diversified, motorized, sportified, indoorized and adventurized.

In Norway, Odden (2008) identified an increased participation in outdoor recreation activities between 1970 and 2004, but the demand became more specialized and diversified, especially among younger people. An increase in motorized activities was also observed from several sources (e.g. Cordell, 2008; Fredman & Heberlein, 2003; Odden, 2008). There is also a trend towards nature-based adventure activities and excitement, as well as wilderness experiences – however, often in combination with high service and comfort levels (Wall Reinius, 2009; Wheeler, 2008). Such changes are related to the direct and indirect consequences of underlying social, technological, environmental, economic and political shifts in society (Nordin, 2005). For example, Buckley (2000) argues that the commercialization of outdoor recreation (including the growth of the retail sector) and increasing urbanization (more people with less everyday contact with nature demanding products and services when visiting nature) are two majo...