![]()

Part I

Adaptation as translation, betrayal, or consumption

![]()

1

Montage of attractions

Juxtaposing Lust/Caution1

Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh

Lust/Caution is quite possibly the most “overdetermined” text in Chinese-language film because of three intertwining issues: adaptation of the most celebrated female author, Eileen Chang, in modern Chinese literature; the ethics of sexual representation; and the politics of patriotism. Ardent Eileen Chang fans (Zhang mi 張迷) eagerly anticipated Ang Lee’s film, the first major adaptation of a Chang story to appear in nearly a decade. Given the lukewarm reception of previous adaptations of Chang’s work, such as Love in a Fallen City 傾城之戀 (Ann Hui, 1984), Rouge of the North 怨女 (Fred Tan, 1988), Red Rose White Rose 紅玫瑰白玫瑰 (Stanley Kwan, 1994) and Eighteen Springs 半生緣 (Ann Hui, 1997), Chang fans were particularly anxious to compare Lee’s film with Chang’s story, to decide whether the seasoned film director was capable of doing justice to Chang’s beguiling literary style.

A contest between two major talents does not amplify the main theme, Lust/Caution, but sex and politics certainly do. Lee’s adaptation of Eileen Chang’s controversial story is doubly scandalous because of its graphic displays of “real” sex and its ambivalence toward collaborators with the enemy (hanjian 漢奸) during the second Sino-Japanese war. Explicit sexual depictions, including shots of frontal nudity and male genitals, caused SARFT (State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television) to issue a self-criticism for approving the production and allowing the release of the finished product in the mainland. Subsequent punitive measures taken against Lust/Caution included suspension of several ongoing co-production projects from overseas,2 and a ban on public appearances by the film’s female lead, Tang Wei, as outlined in the introduction to this volume.3 Charges against the film’s ethical integrity were further intensified with additional criticism of the film’s sympathetic portrayals of the male protagonist, a high-ranking intelligence officer in the puppet Nanjing government during the Japanese occupation. Peng Hsiao-yen’s chapter will treat this topic in greater detail (see Chapter 9).

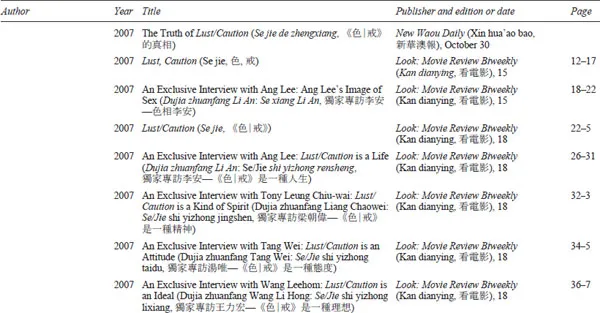

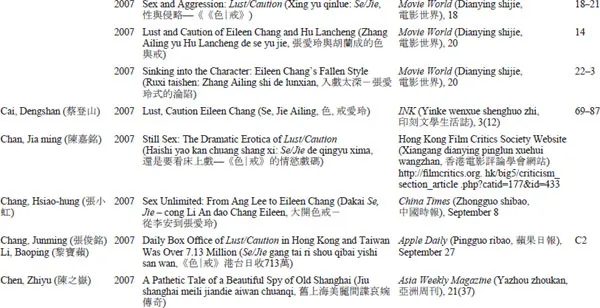

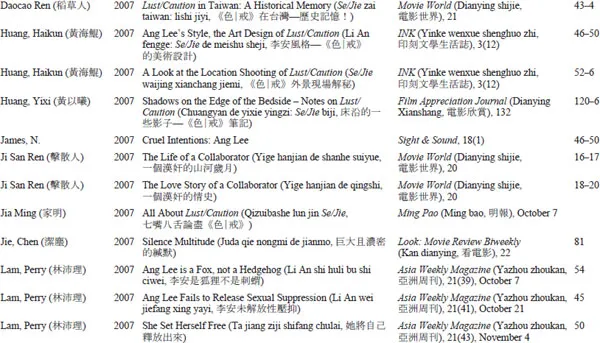

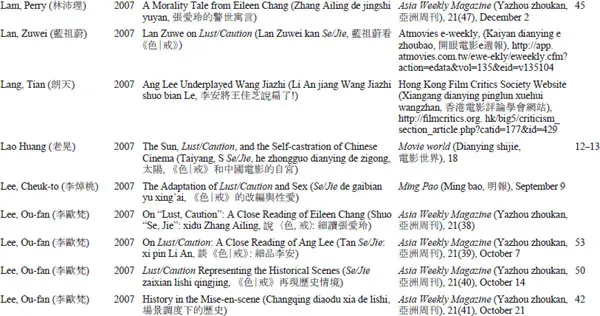

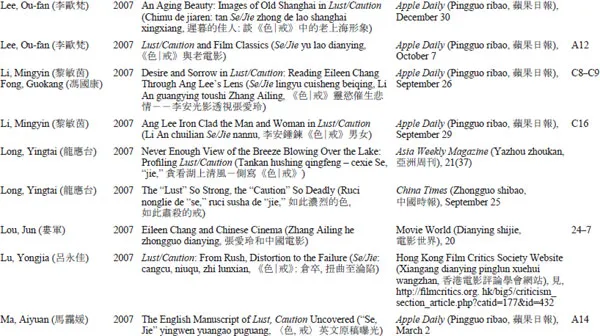

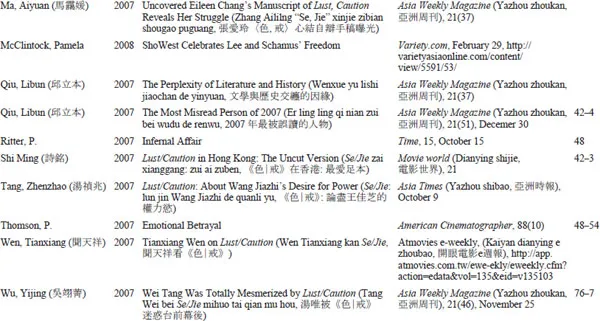

Fidelity (or the lack of it) in literary adaptation, political allegiance and cinematic credibility all contribute to the overdetermined textuality of Lust/Caution. Although Ang Lee repeatedly stated that his film was not meant to be a copy of the story, but was rather inspired by Eileen Chang’s work (Leo Ou-fan Lee, 2008c, p. 59), audiences could not help but examine, interrogate, and authenticate Lee’s re-creation. Between August 2007 and February 2008, I collected a total of 64 pieces of writing about Lust/Caution (see Table 1.1). Authors of these pieces include scholars, critics, journalists, column writers, and historians; of these publications, 18 concern issues of historical representation, 26 pieces discuss sex and politics, and 10 are comparisons between Ang Lee’s adaptation and Eileen Chang’s story. The rest are film reviews and interviews with the cast and crew. There is ample evidence showing a keen juxtaposition of fiction and history, of politics and cinema, of Eileen Chang and Ang Lee and their respective treatment of similar source materials. These three intersecting themes culminated in Leo Ou-fan Lee’s Looking at Lust/Caution: Literature, Film, History (Leo Ou-fan Lee, 2008c). Leo Lee’s book approaches the two texts from the perspective of literature, cinema, and history, offering a valuable taxonomy evaluating the production of the “two geniuses.” The resulting analysis, by juxtaposing film and literature, director and writer, history and fiction, produces a wealth of references that plumb the depths of both texts, leaving significant traces with which to enhance our understanding of politics, love, and libido in wartime Shanghai.

Table 1.1 Articles on Lust/Caution between August 2007 and February 2008

Following Leo Ou-fan Lee, my interest in Lust/Caution is less concerned with the issue of fidelity than of intertextuality between the film and its source novella. Relations between film and literature have always fascinated and troubled scholars of adaptation studies (Thomas M. Leitch, 2007). But when it comes to adaptation criticism, there is a tendency to use the literary text as a prime measure against its cinematic rendition. This has to do with the disciplinary preference given to literature, leading to the evaluation of adaptation from a literary, rather than a cinematic perspective: good adaptation needs to be faithful to its literary source. Another fallacy in adaptation studies is the “discourse of authenticity” that subjugates screen adaptation to the position of a copy inferior to its original (Andrew Higson, 2003, p. 42). In other words, most studies tend to focus on the fidelity, or its lack, of the screen version, leaving the dialectics between the cinematic and the literary unexplored. Fidelity criticism has been under scrutiny by many scholars (Andrew Higson, 2003; Brian McFarlane, 1996; Robert B. Ray, 2001). Its criticism is exemplified in the following passage from Robert Stam’s research on adaptation:

The traditional language of criticism of filmic adaptation of novels, as I have argued elsewhere, has often been extremely judgmental, proliferating in terms that imply that film has performed a disservice to literature. Terms such as “infidelity,” “betrayal,” “deformation,” “violation,” “vulgarization,” “bastardization,” and “desecration” proliferate, with each word carrying its specific charge of opprobrium.

(Robert Stam, 2005, p. 3)

Taking a shot at the “judgmental” language in adaptation criticism, Stam goes on to question the validity of fidelity as a methodological principle:

An adaptation is automatically different and original due to the change of medium. The shift from a single-track verbal medium such as the novel to a multitrack medium like film, which can play not only with words (written and spoken) but also with music, sound effects, and moving photographic images, explains the unlikelihood, and I would suggest even the undesirability of literal fidelity.

(Robert Stam, 2005, pp. 3–4, bold in original)

To understand better the relationship between filmic adaptation and its literary property, as Stam suggests, is to consider Julia Kristeva’s theory of “intertexuality” and Bakhtin’s dialogism. Both theories stressed “the endless permutations of textual traces rather than the ‘fidelity’ of a later text to an earlier one, and thus facilitated a less judgmental approach” (Robert Stam, 2005, p. 4). Similarly, recent theoretical developments in film and literature have begun to favor the intertexual approach to the tension and relation between these two art forms, which emphasizes the interplay of cinema and letters, moving away from the former insistence on their individual textual purity (Mireia Aragary, 2005).

My interest in Lust/Caution shares this post-structuralist suspicion about approaches that privilege the “original.” I prefer to focus on supplements, transmutation, cannibalization, and performance (see Chapter 4 in this volume, by Darrell William Davis) of adaptation. Rather than a judgmental comparison (which seems to be the main agenda of many critics involved in the criticism of Ang Lee’s film), what is at issue comprises the changes, surprises and aesthetics written into Chang’s source. I am attracted by the film’s attempt to realize the literary via the cinematic specificities, and to engage literature by means of film art. In other words, to use Bakhtin’s concept, how is Lust/Caution qualified as a dialogic text to its literary source? And for this, I believe Lust/Caution is a worthy case of investigation, aside from the political and ethical discussions prompted by its content.

There appear to be three readings in my literature review: that the film is an erotic spy thriller; that the story is a ridicule of patriotism; and finally, that the story is an autobiographic act of Eileen Chang herself. Already the story of “Lust” invites several discursive exercises, given its set-up of intertwined personal, political, and carnal relationships. So for Lee the film translator/interlocutor to unlock this system of “the spyring,” the English title of the original story, it takes more than an understanding, but a deeper explanation and perhaps a wry analysis. I am particularly interested in the methods Ang Lee utilizes to illustrate what he takes to be the heart of Chang’s story, the dialectics of lust and caution. My query is sparked by the first image of the film: a close-up of a German Shepherd led by a security guard.

A good film’s opening image sets its overall thematic tone. With careful design, the principal signifier at the beginning often constitutes itself as a visual motif, a key to the unraveling of the mystery, like Rosebud in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane. Lust’s opening shot is a close-up of a German Shepherd. This shot appears again in a slightly different composition prior to the second sex scene. Why the prominent place for a German Shepherd not even mentioned in Chang’s story? What is the meaning of its repetition? These questions might pertain to the film’s engagement with the literary source, the relationship between image and words. By answering these questions, we may also develop a new direction in studying Ang Lee’s film authorship.

A close analysis of the film’s shot relations will be conducted in the following section to answer the above questions. Sergei Eisenstein’s montage theory is surprisingly apt in explaining Lee’s stylistic choices because of its dialectical approach to shot relations, as well as its quest for visual impact and psychological affect, both of which are underplayed in Chang’s novella. In the following I employ Eisenstein’s dialectical montage and montage of attractions theories to examine these hypotheses.

Montage initiated: Deutscher Schäferhund

Following the credit sequence, Lust/Caution presents an image of a Deutscher Schäferhund – a German Shepherd – to begin its narration. This breed is known for its intelligence, obedience and strength, with these dogs often being used as police and military attack dogs. According to World of Dogs website, German Shepherds are not only intelligent but “loyal, faithful, versatile, calm, fearless, courageous, self-confident, reliable, obedient, protective, responsive, alert, aloof and [do] not readily warm up to strangers.” Other adjectives used to describe the German Shepherd include timid, anxious, nervous, aggressive, and fearful. In other words, the breed is both suspicious and watchful. Given these traits, Lee’s choice of the dog for the film’s initial image is not accidental; it is a visual inscription of the second word of the title, jie, “caution,” illustrated vividly by the dark watchful eyes of the dog (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The German Shepherd patrolling (Lust/Caution).

Here Ang Lee enacts a crisp visualizing of “caution,” and this is the concept with which he defines the story of a pair of political opposites carrying on an extramarital affair in occupied Shanghai. By using the image of the dog, Lee offers a distinct filmic rendition of the title: the police dog denoting the functional and character traits of the principal character Mr Yi and his cadre of military force. This visual translation of the title character expands as the close-up of the dog tilts up to show its handler, whose intensely guarded face scans left and right, looking for possible suspects. This is followed by a several short shots of the surroundings of Mr Yi’s residence, peopled by guards, drivers, and more dogs. Caution carries over to the next scene, introducing the scheming tai-tais (wives) at the mahjong table.

In the connotative, “infrastructural” level of signification, the dog image warrants Ang Lee’s entry to Eileen Chang’s world of espionage. To Lee, jie (caution) is the basic component of the story, suggesting the importance of vigilance at any cost, because of our emotional vulnerability in the face of ruthless political vicissitudes. Jie in this context is therefore not to be taken as a concept originating in Buddhism, the set of disciplines and prohibitions used to reach enlightenment. Rather, it means a moral, emotional, and psychological firewall that is constantly under threat. Because threats are everywhere, coming from any direction, from simple corporeal pleasures like food and sex, to subtle ideological conversions like disloyalty and defection, it is crucial for us to keep alert, to be constantly cautious. The motif of “caution” thus permeates the entire film, beginning with an explicit, literary depiction of a police dog, and actualized by a refined set piece of intrigue and doubt, hinting at opacity.

Deutscher Schäferhund redux

Caution alone cannot make up an exciting tale of morality. It must seek a partner, an antithesis, to complete the story of dynamic struggle. Here, lust comes into play. Chang’s treatment of lust is implicit and truncated: “In truth, every time she was with Yi she felt cleansed, as if by a scalding hot bath; for now everything she did was for the cause” (Eileen Chang, 2007a, p. 24). This is the account made by Wang Jiazhi (as the undercover agent playing the role of a lonely wife in order to seduce Mr Yi) of her sexual encounters with Yi. However, Lee’s rendition of this brief and important description is all too blatant, provocative and proscribed, as shown in the three sex acts. The first act is Wang’s initiation, a trial that qualifies her to be approved as Yi’s mistress (presented almost like a rape); the second and the third are hardcore depictions of an intense sexual affair.

The second sex act between Wang and Yi takes places inside Yi’s house when Yi’s wife is out visiting a sick friend. It begins with a passionate reunion, after Yi has gone away for several days. The reunion quickly turns into lusty copulation, which is broken into two parts, foreplay and penetration. Between these two parts is a 10-second interlude showing the watchful German Shepherd led by a guard, patrolling outside the residence (Figures 1.2 and 1.3).

Figure 1.2 Lust (Lust/Caution).

Figure 1.3 Caution (Lust/Caution).

The 35-second-long foreplay (1:40:13–1:40:48) features the nude couple caressing and kissing each other. As Wang’s tongue travels over Yi’s chest, her face, which moves from the left to the right-hand side of the frame, is followed by a matching shot: a medium close-up of the German Shepherd walking towards the left-hand side of the frame, stopping, turning to the center, and looking straight at the spectator. This is followed by a cut back to the bedroom scene, whic...