This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Plains Cree Morphosyntax (RLE Linguistics F: World Linguistics)

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book explores several topics in Cree morphology, syntax and discourse structure. Cree, an Algonquian language, is non-configurational: the grammatical relations of subject and object are not expressed by word order or other constituent structure relations, as they are in a configurational language like English. Instead, subjects and objects are expressed by means of the inflection on the verb. Cree is typical of non-configurational languages in allowing a great deal of word order variation. This study examines in detail aspects of the Plains Cree dialect, giving a valuable insight into the structure of this endangered language.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Plains Cree Morphosyntax (RLE Linguistics F: World Linguistics) by Amy Dahlstrom in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

This dissertation explores several topics in Cree morphology, syntax, and discourse structure. Cree is a non-configurational language: that is, the grammatical relations of subject and object are not expressed by word order or other constituent structure relations, as they are in a configurational language such as English. Instead, subjects and objects are expressed by means of the inflection on the verb.

A primary role in the encoding of grammatical relations is played by an opposition within third person known as obviation. Obviation is a discourse-based opposition distinguishing the person of greatest interest in the discourse (= proximate) from all others (= obviative). When a verb has two third person arguments, it is the distinction between proximate and obviative, marked on NPs and cross-referenced on verbs, that indicates which is subject and which is object.

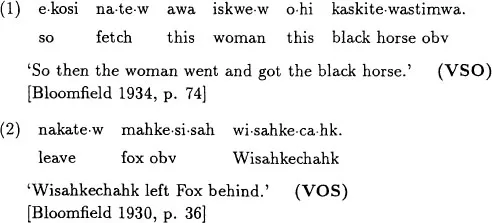

Cree is typical of non-configurational languages in allowing a great deal of word order variation. As seen in the following examples, all six possible permutations of subject, object, and verb are grammatical, and are attested in texts. Obviative nouns are indicated in the interlinear glosses, while proximate nouns are unmarked. All the verbs are suffixed with -e w, which indicates a proximate singular subject and an obviative object.

This introductory chapter presents some background information on the Cree language itself, on the data used here, and on its transcription. The second section provides an overview of material to be covered in later chapters.

1. Background on Cree

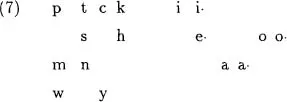

Cree is an Algonquian language spoken across a large area of Canada, ranging from the Rocky Mountains in the west to James Bay in the east, encompassing the central portions of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, northern Ontario, and northwestern Quebec. There are also some Cree speakers in the United States, mostly at Rocky Boy’s reservation in Montana. Plains Cree, spoken primarily in central Saskatchewan and in Alberta, is one of five dialects. The major feature distinguishing the various dialects is the reflex of Proto-Algonquian *1: in Plains Cree, PA *1 corresponds to y, as in PA *mi·le·wa ‘he gives it to him’ (Bloomfield 1946, item no. 81), Plains Cree mi ye·w. The following set of forms for ‘no, not’ illustrates the reflexes of PA *1 in the Cree dialects.

(7) | Plains Cree | namo·ya | ‘no, not |

Swampy Cree | namo·na | ||

Moose Cree | namo·la | ||

Woods Cree | namo δa2 | ||

Atikamek Cree3 | namo·ra |

Ellis 1973 estimated the total number of Cree speakers to be 55,000, with 24,000 speaking Swampy Cree and 21,000 Plains Cree. A more recent figure comes from the 1981 Canadian census, where about 66,000 respondents identified Cree as the language they first learned and still understand (Burnaby 1986, p. 56).

The data used in this dissertation is all from the Plains dialect of Cree. Where possible, textual examples are given to illustrate a point; however, when a syntactic argument requires the negative data of ungrammatical sentences, or when a textual example is not at hand, the textual examples have been supplemented with elicited sentences. The elicited sentences come from fieldwork in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan during the summer of 1985, and from fieldwork with Cree speakers residing in California, in 1984 and 1985. The textual examples are mostly taken from Bloomfield’s two published volumes of texts (Bloomfield 1930, 1934); a few are drawn from texts collected in Saskatoon, and from Ahenakew 1987b.

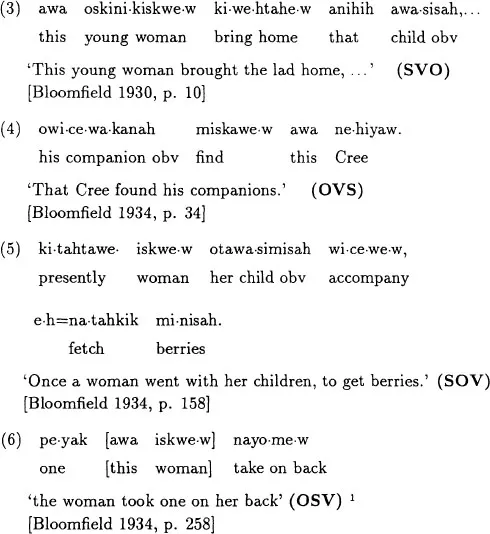

Plains Cree has a simple phonemic inventory:

The stop series is voiceless unaspirated; t. is alveolar, c is an affricate varying from alveolar to alveo-palatal; s similarly shows some variation from alveolar to alveo-palatal. Vowel length is distinctive. It is sometimes convenient to distinguish two underlying sources of i: /i/ and /e/, as well as two underlying sources of t: /t/ and /θ/. This allows certain morphophonemic alternations to be easily represented, as discussed in chapter 2, section 2.5. However, /e/ and /θ/ are never written in the Cree orthography.

Examples from my fieldnotes are given in the standard orthography developed for Cree, except that vowel length is indicated by a following raised dot, rather than by a macron or circumflex over the vowel, and certain preverbs have been set off by an equals sign, rather than by a hyphen, for reasons explained in chapter 2, section 2.2.2. (For a discussion of the standard orthography, see Wolfart and Ahenakew 1987.) The transcription used by Bloomfield (1930, 1934) differs from the standard orthography in a number of ways, and the examples taken from Bloomfield’s texts have been changed in some orthographic respects. As above, vowel length is indicated by a following raised dot. Bloomfield’s u is here written o, his ä is here e, and his ts is here c. These are not the only places in which the transcription used by Bloomfield differs from current orthographic practice. He also wrote word-final h, which is not phonemic, and indicated some instances of syncope of short vowels, external sandhi, and variation in vowel length. These features of Bloomfield’s transcriptions, while not standard, have been retained in the examples cited here. I have added interlinear glosses, while maintaining (in most cases) Bloomfield’s English translations.

The syntactic investigations reported here have been greatly aided by previous analyses of Cree morphology: most of all by Wolfart 1973. Chapter 2 presents a lengthy discussion of inflection, as a necessary preliminary to what follows, but the discussion here is more limited in scope than that given by Wolfart. For details on the less common verbal paradigms, as well as an overview of the varieties of Cree word formation, the reader is referred to this excellent study. The summary of inflection given in chapter 2 is also less complete than the presentation found in Ahenakew 1987a,4 a clear and detailed discussion of noun and verb classes, basic paradigms, and morphophonemic alternations. For readers unfamiliar with Algonquian languages, Ahenakew 1987a is the more accessible description. Other resources on Cree include the dictionaries of Lacombe 1874 and Faries 1938, and the wordlist of Bloomfield 1984.

2. Overview of following chapters

Chapter 2 describes inflection, especially the complex system of verb inflection. As will be seen in chapter 5, the inflectional features associated with the verb serve to link the arguments of the verb to the proper grammatical functions. The marking of these features on the verb, however, is accomplished in a rather unusual manner. Most of the affixes encoding person and number features are not specialized for subject or object, nor are the affix positions themselves dedicated to encoding information about a particular grammatical function. Rather, special suffixes on transitive verbs link the person and number features of the other inflectional affixes to subject and object.

Transitive verbs may be divided into two sets, called direct and inverse, based upon the particular suffix used to perform the linking of features with grammatical functions. Inverse verbs with obviative third person subjects and proximate third person objects display a discourse functional similarity to passives in other languages. Syntactically, however, the direct and inverse verbs are both active. Chapter 3 presents the syntactic analysis of the direct and inverse forms, contrasting them with the genuine passive of Cree. The chapter also contains a discussion of constructions which may be used as tests for grammatical relations in Cree.

Obviation is taken up in chapter 4. Obviative thir...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1. Introduction

- Chapter 2. Inflection

- Chapter 3. Direct, inverse, and passive verbs

- Chapter 4. Obviation

- Chapter 5. Lexical processes

- Appendix: ‘A Brave Boy’

- Bibliography