This is a test

- 258 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Previous research on this topic has not focused on nutrition-specific social support for elderly women. This unique study seeks to describe and explore the current situation in a group of elderly women living alone in government subsidized housing.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Nutrition Support to Elderly Women by Michell Pierce in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicina & Nutrizione, dietetica e bariatria. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

The growing elderly population suffers from a disproportionately large incidence of chronic and acute illnesses, as well as mental and physical disabilities. The Surgeon General’s report on Nutrition and Health points out that “dietary, economic, and social support programs” render significant health benefits to older adults with these chronic conditions (U.S. DHHS 1988). Optimal nutrition speeds recovery from acute illnesses and can help improve or maintain functional status and quality of life (Administration on Aging 1994; Gray-Donald 1995; Palmer 1990; Position of the American Dietetic Association 1996; Rosenberg and Miller 1992).

Supportive relationships can also impact positively on health and quality of life during the later years (Antonucci and Akiyama 1995; Bloom 1990; Broadhead et al. 1983; Grundy, Bowling, and Farquhar 1996). Support from friends and family enhances self-care practices, promotes the use of services, and increases life satisfaction (Hansson and Carpenter 1994). In addition, social support is believed to exert a beneficial effect on food intake (Coe and Miller 1984; Davies and Knutson 1991; Krause and Wray 1991), thereby further increasing the overall influence of social support on health.

The importance of social relationships on the dietary adequacy of elders was recognized at the Nutrition Screening Initiative (NSI) Consensus conference (White 1991). The NSI identified social isolation as one of seven key risk factors predicting nutritional health in older adults. Title IIIC of the Older Americans Act, which mandates nutrition services for the elderly, includes the opportunity for social interaction as an important goal of the program. Congregate meal participants have indicated that the opportunity to socialize is valued (Administration on Aging 1983; Falk, Bisogni, and Sobal 1996; Neyman, Zidenberg-Cherr, and McDonald 1996; Van Zandt 1986).

Thus, public programs incorporate the premise of a positive link between strong social relationships and a high quality diet. However, few research studies have actually been able to document this association. Little is known about the types and attributes of social relationships that influence food patterns. The objective of this study was to explore, in depth, specific aspects of social relationships and their association with dietary quality.

Social Relationships

The social network is the set of persons who interact with the focal subject. Typically, network structure is defined in terms of nodes (people) and ties (bonds between nodes) (Antonucci 1985). Structural identifiers, such as size, stability, homogeneity, complexity, and density are used to distinguish properties of the network.

The social network may contain both informal (kin, friends, neighbors) and formal (professional, government) sources. Both provide various functions that impact on the physical and mental status of the focal subject. By integrating the literature from research on social isolation, loneliness, and social support, Rook (1985) has suggested a schema for conceptualizing the functions of social bonds.1 Her interpretation is useful in understanding the influence of social relationships on food intake patterns.

Rook (1985) proposes three functions of social bonds: companionship, social control, and social support. Companionship provides intimacy and pleasure. The primary function of companionship is to increase feelings of self-worth and self-esteem. Social control exerts a regulatory function. Social ties inhibit deviant behavior while promoting healthful habits, especially during transitional periods. Social support operates during times of need. Tangible aid, information, or emotional support may be extended to offset debilitating effects of a stressful event.

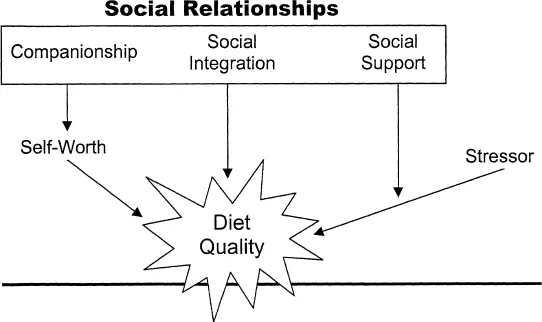

In Figure 1, a nutrition-specific adaptation of Rook’s model is proposed. Rook explains that the presence of a companion increases feelings of self-worth. Heightened self-worth leads to mental well being, happiness, and life satisfaction. In the nutrition-specific model, the increase in self-worth has a beneficial impact on dietary quality (Coe and Miller 1984; Schafer, Keith, and Schafer 1994). The influence of companionship on diet quality is therefore indirect, operating through self-worth.

Figure 1: Proposed model of the association between social relationships and dietary quality (adapted from Rook 1985)

The second function of social relationships, social control, is presented as social integration in Figure 1. Social integration is the degree to which the focal individual feels a part of the community. The more socially integrated, the more control society would be expected to exert. The alternative is social isolation. A gradual withdrawal from social activities often occurs during the later years (Sauer and Coward 1985). Rook proposes that the subsequent social isolation could provoke role ambivalence and inadequate self-care behaviors. For instance, a socially withdrawn individual may choose to eat cold cereal three times a day and not experience the normative guilt of such a deed. Thus, in the nutrition-specific model, social integration would have a direct and consistent effect on diet quality.

In contrast, social support, the third function of social relationships, is only activated in response to a stressful occurrence in the life of the focal subject. The goal of support providers is to help the focal individual through a short- or long-term period of difficulty. In the nutrition-specific model, social support moderates the influence of a potential nutrition-related stressor. For example, a newly diagnosed diabetic must change her eating patterns to follow an explicit, prescribed diet. Without diet instruction or encouragement, she is likely to have poor dietary compliance and a poor prognosis. However, with optimal support from health professionals, family, and friends, she can control her diabetes with a high quality diet.

In summary, social relationships are postulated to affect diet quality through indirect (companionship), direct (integration), and interactive (support) modes. Unfortunately, prior studies investigating social relationships and diet quality have not always employed similar definitions. For instance, structural measures of social integration have been included most frequently, but have been labeled as indices of social support. Furthermore, some prior indices simultaneously assess more than one function. The following discussion of research findings shows how multiple definitions of the social relationship construct have led to uncertain conclusions.

The literature search was limited to research involving older adults. Both foodways (Hendricks, Calasanti, and Turner 1988) and social relationships (Antonucci 1985) vary with age. Although the category of older adults contains a very heterogeneous mix, inclusion of younger individuals would have compelled even greater variability.

Prior Research

Although nutrition researchers have endeavored to investigate the influence of social relationships on diet quality in the elderly, the proxy measures most often employed have not been adequate to address the complexity of the constructs. The following discussion first describes research efforts that have included a nonspecific measure of social relationships. The results of research employing indices that can be categorized according to the adapted model are then described.

Living Arrangement

Most frequently, an assessment of social bonds has been included in studies examining multiple psychosocial factors. Thus researchers have needed a simple measure to represent the complex phenomena of social relationships. The most typical proxy measure is the living arrangement of the older adult, that is, whether the elder lives alone or with others. Living alone is believed to increase vulnerability to inadequate social interaction, a lack of companionship, and insufficient social support (Rubinstein, Lubben, and Mintzer 1994; White 1991). In other words, living alone is expected to negatively impact all three of the functions of social relationships in the proposed model.

Some studies have documented that older adults who live alone consume a less nutritious diet than individuals who live with others (Bianchetti et al. 1990; Reid and Miles 1977; Slesinger, McDivitt, and O’Donnell 1980). However, most researchers have found no relationship (Kolasa, Mitchell, and Jobe 1995; LeClerc and Thornbury 1983; Payette et al. 1995; Posner, Smigelski, and Krachenfels 1987; Ryan and Bower 1989; Sem et al. 1988; Zipp and Holcomb 1992).

Davis et al. conducted detailed analyses of National Health and Examination Survey 1971 to 1974 (NHANES I) and Nationwide Food Consumption Survey 1977 to 1978 (NFCS) data (Davis et al. 1985 and 1990, respectively). The results of both surveys indicate that older males who live alone have the poorest diets. The diet quality of older females who live alone is equivalent to the diet quality of older adults who live with others. Similarly, Frongillo et al. (1992) and Westenbrink et al. (1989) found that the combination of male gender and living alone appears to increase risk of a deficient diet.

Horwath (1989) suggests that gender and living arrangement are indicators of larger social forces. In this elderly cohort, females have been the traditional providers of food and nutrition. Simultaneously, females have shouldered the responsibilities of maintaining social networks. The poor diet quality of elderly men who live alone may result from limited knowledge of food procurement and preparation methods. An inadequate support network may further exacerbate the situation.

In summary, the results of research examining the association between living arrangement and diet quality suggest that living alone may have a slight, negative impact on food intake patterns, especially for males. In other words, for certain groups of older adults, inadequate opportunities for socialization may inhibit healthy eating behaviors. This conclusion is further supported by research of Hubbard, Muhlenkamp, and Brown (1984). Their assessment of the interpersonal resources of older adults tapped all three functions of social relationships. Elders with strong social resources employed more positive health behaviors, including good nutrition practices, than elders with low social resources.

Companionship

According to Rook (1985), companionship includes both pleasurable camaraderie and emotional sharing. Pleasurable camaraderie refers to joint recreation and leisure time activities. Emotional sharing is typified by confidential discussions of personal feelings. The results of these activities are enhanced mood and increased self-worth. Mutually shared affection also results in decreased loneliness, increased happiness, and greater life satisfaction (Rook 1985).

Only two research studies have examined the relationship between companionship and diet quality in the elderly. Hanson, Mattisson, and Steen (1987) assessed perceived availability and adequacy of emotionally close relationships in 480 males, age 68. Analyses of diet history data revealed that 20% of the men had diets of poor quality, specified as one or more nutrients below a defined cut-off. Chi-square results indicated no statistically significant association between diet quality and level of perceived closeness. However, a trend was apparent in the expected direction. Men with poorer diets did report lower relationship availability and adequacy ratings than men with good diets. The data categorization methods and use of chi-square may have weakened the ability to detect statistically significant associations (Blalock 1979).

In the second study examining companionship and diet quality, Heller and Mansbach (1984) assessed three aspects of close relationships. Forty-three elderly women reported the number of intimates in their network, the proportion of intimates to total network, and the frequency of contact with intimates. No association with the intake of four nutrients was found. The researchers attributed the lack of significance to the small sample size and the limitations of a 24-hour recall to determine diet adequacy.

Referring to the nutrition-specific model, the proposed association between companionship and diet quality is indirect. In support of the model, Heller and Mansbach (1984) did find that the proportion of intimates to total network entered into a predictive multiple regression equation for life satisfaction. However, in their sample, life satisfaction was not related to the intake of any of the four nutrients.

Only a limited number of research studies have explored the pathway from self-concept to diet quality (Witte, Skinner, and Carruth 1991). Schafer and Keith (1982) noted no relationship between self-esteem and diet in their sample of single and married older adults. In contrast, Learner and Kivett (1981) found that elders who perceived problems with their diet also reported lower morale. The researchers credited the low morale to loneliness. The findings of Walker and Beauchene (1991) are in agreement with this proposition. Participants in their study completed the UCLA Loneliness Questionnaire and three days of diet records. Loneliness was associated with poorer nutrient intakes.

In conclusion, the nutrition-specific model suggests that companionship influences diet through the effect on self-worth. Only two studies were found which examined a direct relationship between companionship and diet quality in older adults. Neither study found a significant association. Furthermore, only four projects have considered the link between attributes of self-concept and diet. Results are inconclusive. Of the three dimensions of social relationships, the influence of companionship on diet quality appears the least well understood. Future studies are needed in this area.

Social Integration

Rook (1985) posits social integration as the second function of relationships. The unique contribution of integration lies in the regulation of behavior. Individuals who are socially embedded are more likely to follow cultural norms. Social roles and obligations provide guidelines for appropriate behaviors. The input of others deters socially integrated individuals from deviant conduct and encourages healthful activities, such as good nutritional habits.

One dimension of social integration is membership in a family. The role of spouse or parent carries certain responsibilities, but does not always indicate emotional closeness (Seeman and Berkman 1988). In a sample of 314 married older adults, Mullins and Mushel (1992) found that 51% did not feel emotionally close to their spouse. Of 757 who were parents, 40% were not close to any of their children.

Regardless, the socially defined roles and responsibilities as spouse or parent may still be expected to encourage self-care practices. However, studies examining these attributes have not consistently shown a relationship to eating patterns. McIntosh, Shifflett, and Picou (1989) found that married individuals had better intakes of vitamin/minerals, protein, and calories than did unmarried persons. Other researchers have found no relationship between marital status and diet quality (Hunter and Linn 1979; Sem et al. 1988). Sem et al. did note more “always single” elderly in the group with the lowest diet score. In contrast, Schafer and Keith (1982) found that elderly, single females had better diets than married couples.

Davis et al. (1985) simultaneously considered marital status and gender. They reported that males who lived with a spouse had better diets than males who lived with others. Marital status had no association to diet quality in females. Number of children (Cohen and Ralston 1992; Payette et al. 1995) and closeness to children (Cohen and Ralston 1992) have been found to be unrelated to nutrient intakes.

A somewhat related measure of social integration is mealtime companionship. Eating is considered a social activity. Furthermore, elders often engage in food activities simply because they offer an opportunity to socialize (Falk, Bisogni, and Sobal 1996). One informant of Howarth (1993, 74–75) reported:

“I should say I lost my husband three years ago. And he (the neighbor) used t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Methods

- Chapter 3: Description of the Subjects

- Chapter 4: Nutrition-Related Concerns and Proffered Help

- Chapter 5: Nutrition-Related Social Support

- Chapter 6: Food Intake and Dietary Adequacy

- Chapter 7: Functional Status, Social Support and Dietary Quality

- Chapter 8: Conclusions

- Appendices

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index