This is a test

- 325 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The World of Theatre is an on-the-spot account of current theatre activity across six continents. The year 2000 edition covers the three seasons from 1996-97 to 1998-99, in over sixty countries - more than ever before. The content of the book is as varied as the theatre scene it describes, from magisterial round-ups by leading critics in Europe (Peter Hepple of The Stage ) and North America (Jim O'Quinn of American Theatre ) to what are sometimes literally war-torn countries such as Iran or Sierra Leone.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The World of Theatre by Ian Herbert, Nicole Leclercq in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ARGENTINA

Francisco Javier is a stage director of longexperience and Secretary of the Argentine Centre of the International Theatre Institute.

In a general overview of Argentine theatre in recent years, traditional productions have been much more frequent than those seeking a more experimental form. However, it is worth devoting our attention first to the smaller group, because it is those which suggest a possible path of development for Argentine theatre.

Such a movement seeks above all to produce pieces which deliberately distance themselves from everyday life, in such a way that the whole system of signifiers – space, spoken and gestural discourse of the actor, lighting, scenography – comes together to make an artistic whole with a value of its own, the result of an apparently free and spontaneous act of play. It has thus produced resonances with movements in world theatre which have always attracted Argentine theatre-makers, such as Vselvolod Meyerhold’s expressionism, Antonin Artaud’s theatre of cruelty, Tadeusz Kantor’s theatre of death, Eugenio Barba’s anthropological theatre and the imagistic theatre. So that what is told or presented appears on our stage like a reflection in a broken mirror: the spectator watches a series of fragments without being able to understand the links that join them. In this field, El pecado que no se puede nombrar (The Sin That Dares Not Speak Its Name) based on the plays and characters of Roberto Arlt, is a paradigmatic work not only because it brilliantly illustrates this new tendency, but also because it expresses in an exceptional manner the porteño spirit of the inhabitants of Buenos Aires (which began life as a port). The theatre form which has portrayed us most authentically, at least as far as concerns Buenos Aires, is the discépolo, the revue sketch or playlet, which in Arlt’s works were an essential point of reference. This production was presented by the theatre group Sportivo, directed by Ricardo Bartis.

Zooedipus, from the group Periférico de Objetos under the direction of Daniel Veronese, Emilio Garcia Wheby and Ana Alvarado, offers a heightening of the specific language of theatre and its ideological constructs in an attempt to put it on a plane with philosophy. In it, everything which might affect the sensual reaction of the spectator is presented violently on stage. Here, theatre merges with dance, the plastic arts, music, pantomime, guignol and scenic design. Veronese has produced other works, employing a form of concise and unambiguous dialogue, which portray engrossing conflicts, constantly hiding and revealing the changes of fortune which the characters undergo. Examples are Equivoca fuga de señorita apretando en el pecho un pañelo de encaje (Doubtful exit of young lady holding a lace handkerchief to her chest) and Algunos viajeros mueren (Some Travellers Are Dying).

In Alejandro Tantanian’s Un Cuento Alleman (A German Story) a very open language encompasses a varied intertextuality; it consists of quotations from the work of other authors as much as his own – his own contribution lies in narratives and long soliloquies. Tantanian is also the author of La tercera parte de la mar (The Third Part of the Sea), directed by Roberto Villanueva.

Rafael R Spregelburd’s La Modestia (Modesty) interconnects two stories which take place in different times and places; the same actors each play several characters. Time and place in the play are matters of theatrical convention. In Rascando de la cruz (Scratching the Cross), the writer puts himself into another reality to speak about Argentine matters, and in En tanto las grandes ciudades (Great Cities the While) he approaches contemporary problems through biblical themes.

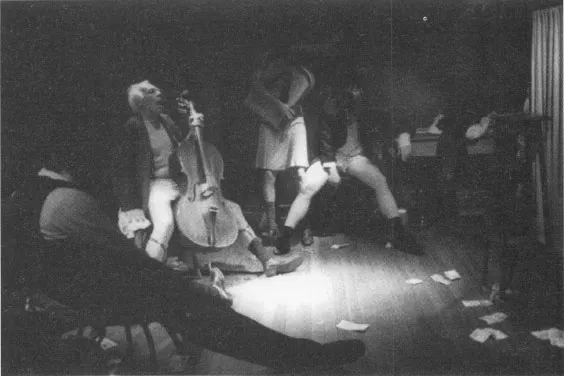

From Ricardo Bartis’ production of El pecado que no si puede nombrar

(photo: Andres Barragan)

Dibujo sobre un vidrio empañado (Drawing on a Misted Window) and La mano en el frasca en la caja en el tren (The Hand in the Bottle in the Box in the Train) by Pedro Sedlinsky reveal a writer who can play in an astonishing way with strong visual images and use spoken discourse to fragment them. The plays were directed respectively by Francisco Javier and Roberto Castro. Some of these productions ran long and well enough to win praise from the newspaper critics, specialised reviews in theatre books and journals, transfers to mainstream theatres and invitations to international festivals. This happened in the case of the plays mentioned above.

In the same category, mention should be made of El Amateur (The Amateur) by Mauricio Dayub; La experiencia Damanthal (The Damanthal Experience) by Javier Margulis, Cinco puertas (Five Doors) by Omar Pacheco and Un Hamlet de suburbio (A Suburban Hamlet) by Alberto Felix Alberto; and plays nearer in form to visual theatre, such as Cachetazo de Campo (A Country Cuff) by Federico de Leon, and A pocos kilómetros del epicentro (A Few Kilometres from the Epicentre) by Ita Scaramuzza; we may also note El caso Marta Stutz by Javier Daulte in a production by Diego Kogan, which tries to resolve an impossible puzzle behind a criminal act, the rape and murder of a young girl; Living, ultimo paisaje (Living, the last Landscape) by Ciro Zorzoli is a clear-sighted examination of memory and of the way in which recollection can apply a demystifying vision.

These developments have also been affected by the contribution of a number of dance-drama groups. In exploring the outer limits of both disciplines, their directors have produced a remarkably rich form of theatre. This is the case with shows such as Nucleodanza, directed by SusanaTambutti and Margarita Bali. In the category of fantasy-theatre, Silvia Vladimisky and Salo Pasik offered Espirales. The El Descueve group produced collective work, while Arnica and Anticos were groups directed respectively by Mabel Dai Chee Chang and Miguel Robles.

The written dramatic text is undergoing changes similar to those to be seen in staged works. Reading it, one is confronted with characters who have lost their identity and wholeness, who have no personal history, who are dominated by ambiguity and the absence of definition, who exist more as stock figures than as the characters expected of traditional theatre. These are characteristics which appear clearly in a play by Luis Cano which has just won first prize in a city playwriting contest. Its title is La Bufera (The Swamp). Cano is also the author of Socavón (The Great Void).

Many of these new playtexts have been published and won prizes in the growing number of competitions that are taking place. It is curious that in a time when publication is becoming more and more difficult (because of a lack of interest in theatre on the part of the publishing houses, as well as a lack of sales for published plays), there has been a great growth in self-published work, translations published in the journals – such as Teatro Siglo XX, CELCIT and Funambules – and the generous circulation of typed scripts. The same thing happens with dozens of more traditional theatre texts, often very good ones.

Strange as that may seem, and in spite of the difficulties it implies to be inherent in getting a ground-breaking piece published, it is notable that all these new writers have nevertheless been able to put their work to the test on stage. This has occurred for two reasons, in my view: on the one hand, there is the interest of the actors and directors, who became interested in new forms ahead of the writers themselves (almost all the examples I have given were the work of directors and actors); and on the other, there is the increase in small theatres dotted about the city, which have given room to the most innovative and the most financially risky projects. But none of this could have happened without the remarkable response of the public. Attracted by an atmosphere of constant reinvention like that on which the cinema prides itself, stimulated by the increased speed of their means of communication, by curiosity and a desire to break the power of the critics, they have been propelled into the theatres by this wind of change.

It should be added that the context for this time of renewal in our national theatre scene could not have been more propitious. Established writers of the last fifty years, such as Roberto Cossa, Osvaldo Dragún, Carlos Gorostiza, Ricardo Halac and Eduardo Rovner have continued to hold the stage, in productions by directors of very much the same generation and outlook. The direct, positive relationships they have set up with the public have created a climate favourable to the new theatre of change.

In this category of theatre, which might be called the standards, we have seen runs of the following plays: from Roberto Cossa, the writer who has shown perhaps the greatest development over his career, came El Salvador (The Saviour), directed by Cossa himself with Daniel Marcove, and performed by Maria Cristina Laurenz and Hugo Arana with decor by Tito Egurza. Griselda Gambaro was in evidence with De profesión maternal (Occupation, Mother), directed by Lara Yusem with design by Graciela Galán, and also with a play written in the Seventies, Dar la vuelta (Taking Turns), directed by Lorenzo Quinteros, designed by Carlos di Pasquo. Actor-writer Eduardo Pavlovsky was there with Poroto (The Bean), directed by Norman Briski. Roberto Villanueva staged La cena (The Dinner) by Roberto Perinelli; another Laura Yusem production was Rápido nocturno, aire de fox-trot (Fast Nocturne to a Fox-Trot Tune) by Mauricio Kartun, starring Ulises Dumont, Alicia Zanca and Jorge Suárez; Richard Halac brought in Frida Kahlo, lapasion (The Passion of Frida Kahlo), with Virginia Lago in the title role, under the direction of Daniel Suárez Marsal with decor by Alberto Negrín; Carlos Gorostiza, Abú, doble historia de amor (Giant Stride, a Double Love Story), with Osvaldo Bonet; Carlos País, Club Atlético madera de oriente (East Wood Athletic Club); Manuel González Gil adapted and directed Porteños from texts by Roberto Fontanarrosa, performed by Daniel Fanego, Horacio Fontova, Gabriel Goity, Osvaldo Santoro and Gastón Pauls; from Elio Gallipoli came Botánico (Botanic); also Tango pour Paul (Tangofor Paul) by Raúl Peñarol Méndez, directed by Andrés Bazzalo; Divordo, curva peligrosa (Divorce, Dangerous Curve) by Luis Agustoni; Cocinando con Elisa (Cooking with Elisa) by Lucia Laragione performed by Norma Pons and Ana Iovino; and Venecia (Venice) by Jorge Accame. As well as these premieres there was a series of important revivals, all showing the vitality of Argentine theatre.

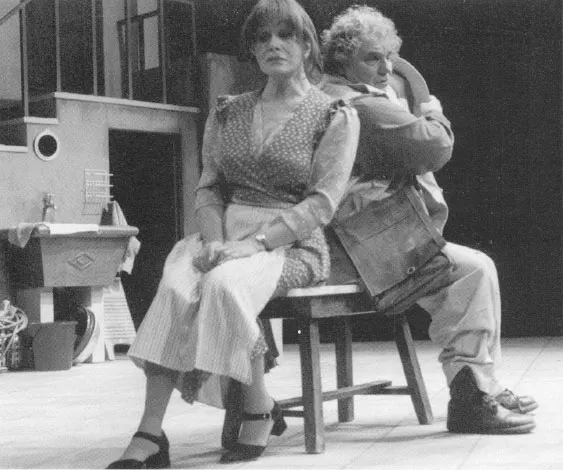

Ulises Dumont, Alicia Zanca and Jorge Suárez in Rapide nocturne aire de fox-trot by Mauricio Cartun

(photo: Carlos Flynn)

María Cristina Laurenz and Hugo Arona in El Salvador by Roberto Cossa

(photo: Carlos Furman)

Latin-American theatre was also in evidence in 1997 and 1999 with plays by Victor Manuel Leites, Adriana Genta, Marco Antonio de la Parra and others. And during these three seasons, there were of course productions of the great foreign classics such as Shakespeare or Calderón, and innovative modern playwrights from the world stage like Heiner Müller, Steven Berkoff, Bernard-Marie Koltès and Thomas Bernhard. In the large regional centres, theatrical activity grew in a remarkable way, especially after the introduction of the National Theatre Law, which gave financial precedence to small theatres and amateur groups. All of this is likely to redraw the map of regional theatres, an event which has long been awaited, and produce a balanced notion of Argentine or national theatre.

As for the suppliers of support skills, such as designers and musicians, they too have had to move from a creative environment based on realism to the theatre of dissent, which has allowed them to demonstrate their adaptability. Among them can be named the designers Tito Egurza, Graciela Galán, Guillermo de la Torre, Jorge Ferrari, Alberto Negrín, Alberto Bellati, Pepe Uría and Carlos di Pasquo; and among the musicians Jorge Valcarcel, Mariano Cossa, Carlos Gianni, Víctor Proncet and Edgardo Rudisky.

During this time two important new events for the country took place: the Festival of Buenos Aires, in 1997 and 1999, and Argentina’s second visit to exhibit at the Prague Quadriennale of Stage Design, in 1999. In 1998 the Argentine Centre of the International Theatre Institute set up the Saulo Benavente Prize, in tribute to the man who gave great energy to the Argentine Centre during thirty years as its Secretary General. The prize celebrates overseas theatre groups appearing in our country, and has a jury made up of two very respected critics from the most important newspapers of Buenos Aires, Olga Cosentino of Clarín and Susana Freire of La Nación, together with five members of the Argentine ITI Centre, Marcela Sola, Elisa Strahm, Juan José Bertonasco, Jorge Hacker and Julio Piquer. In 1998, the prize went to Anna Karenina, performed by the English company Shared Experience. It was presented at the Cervantes National Theatre during the celebration of World Theatre Day.

Theatre studies have achieved a high level of development, above all in the Universities, in their research departments and their courses in theatre theory. Each year, the Getea group from the Institute of Argentine Art of the University of Buenos Aires organises an International Congress of Argentine and Latin-American Theatre. The participants in the 1999 Congress included Anne Ubersfeld from France, Marco de Marinis from Italy and Josette Féral from Canada, as well as a large number of other professors and researchers from America and Argentina.

The Institute of Performing Arts from the same faculty organised an interpretation workshop in 1998, led by the French professor Patrice Pavis, an International Critics’ Forum, organised by Ana Seoane, with the participation of Juan Antonio Hormigon, editor of the Spanish theatre journal ADE (the magazine of the Spanish Association of Stage Directors), and a tribute to the professor and researcher Raúl H Castagnino, who died recently. In this overview one should highlight especially the publishing work which has helped to spread knowledge of the work, not only of playwrights from at home and abroad, but also of those researchers who study the theatre as a cultural and artistic phenomenon.

AUSTRALIA

Jeremy Eccles is an English-born cultural commentator resident in Sydney, Features Editor of the State of the Arts magazine group and a correspondent for International Arts Manager and The Stage in London.

There’s a strange irony at work in Australian theatre (and dance) at the moment. Just as what I see appears to be in stasis or even regressing, so the world suddenly (and belatedly) seems hungry for our product. No European festival is complete without Strange Fruit or Legs on the Wall doing their finely honed physical theatre thing; Cloudstreet has surely only just begun an epic touring life with 1999’s outing to London, Dublin and Zurich; and the Olympics in Sydney later this year (2000) have created a curious demand for Australia’s art – with National Weeks planned in London, Amsterdam, Hanover and elsewhere, and Aboriginal art – fantastically – to be found in the Hermitage Palace, St Petersburg, just about as far removed from its r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Foreword

- The World of Theatre 2000

- International Theatre Institute