eBook - ePub

Las Abejas

Pacifist Resistance and Syncretic Identities in a Globalizing Chiapas

This is a test

- 300 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Las Abejas came to be known by the international community as the civil counterpart to the neozapatista movements and as a Christian pacifist movement. This book presents the voices of Las Abejas and of numerous collaborators alongside an innovative theoretical analysis of the dynamics of identity construction. The uniqueness of this study is the analysis of the role of international human rights observers in relation to indigenous communities in resistance. In this fascinating study, Marco Tavanti explains how cultural, religious, political, human rights and nonviolent frameworks combine in a syncretic identity of resistance.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Las Abejas by Marco Tavanti in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

LAS ABEJAS

CHAPTER ONE

Las Abejas and the Acteal Massacre

IN NOVEMBER 1999, THE INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATION CALLED Las Abejas (The Bees) organized a celebration of thanksgiving for retiring Bishop Samuel Ruiz in the village of Acteal in the Highlands of Chiapas, Mexico. Tatik (father) Samuel, as Las Abejas affectionately call him, worked in Chiapas for more than forty years. During that celebration, Bishop Ruiz spoke about the ‘globalization’ of Acteal and how Las Abejas had expanded their worldview as they continued to welcome visitors from all over the world. In his words:

A few months after the Acteal massacre, Antonio came to me saying how people from all over the world were coming to Acteal. ‘Tatik Samuel,’ he said, ‘People from all five continents of the world are coming to visit us in Acteal!’ And I thought to myself: Antonio, who always lived in these villages of the Highlands, probably does not know where these continents are. But then he said: ‘There are even people coming from Australia and we received an invitation to go there for a conference on indigenous people of the world.’ I realized my mistake. Acteal is indeed at the center of the world and you [people of Acteal] knew it (Fieldnotes, 8 November 1999).

I observed first hand how Las Abejas rapidly grew in their understanding of being in a globalizing Chiapas by examining a world map hung on the organization’s office wall in Acteal. Las Abejas’ Mesa Directiva (Board of Directors) received this map from a pastoral worker of the San Cristóbal de Las Casas (SCLC) Diocese a few weeks after the Acteal massacre. Since that tragic day on December 22, 1997, frequent international delegations and human rights observers from various countries have come to visit Las Abejas in Acteal. In several interviews, the Tzotzil indigenous people of Las Abejas told me how that world map was a way to visually locate the national origin of visiting people in relation to Acteal. Visit after visit, it was like opening themselves to the world as they drew more lines linking Acteal to numerous countries and cities all over the world. The Mesa Directiva commented how later those links symbolized Las Abejas’ many connections with numerous foreign organizations. Acteal soon became a place where international coalitions for solidarity and for the defense of human rights were established and implemented.

The ‘globalization’ of Acteal and the international networks between Las Abejas and various international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) reflect some of the dynamic processes of Las Abejas’ construction of their collective identity. One can easily agree with the idea that, from a sociological perspective, all identities are constructed. The real question is how identities are formed and under which conditions they are represented and transformed (King 1997).

THE 1992 FORMATION OF LAS ABEJAS

The Sociedad Civil Las Abejas1 emerged as a collective response to land conflict and political injustice. On December 9, 1992, representatives from 22 communities gathered in Tzajalchen, in the municipality of Chenalhó and formed a coalition to defend a woman’s rights to own land. Thirty days earlier, in the nearby community of Tzanembolom, Augustín Hernandez Lopez declared that he did not want to share 120 hectares of inherited land with his two sisters, Catarina and Maria. His argument was that ‘as women’ they did not have any rights to land (Hidalgo 1998, 54).

As is typical with disagreements in this indigenous community, members of the community gathered to examine the quarrel. The Tzanembolom community decided to divide the land into three equal parts, giving justice and equal rights to all the siblings. Because about 60 hectares were not registered with the certificate of Agrarian Rights, the community suggested to partition the remaining land. The brother, in disagreement with what the community decision, handed the unregistered land over to some inhabitants of the Yiveljoj, Las Delicias, and Yabteclum communities asking for their support. Then, Augustín Hernandez Lopez and this group kidnapped the two sisters along with their children and forced them to sign documents and renounce their land (CIACH 1997, 3). In response, several representatives from 22 communities organized in support of the two sisters and defended their communities from possible attacks (Barry 1995).

Thinking about a name for this newly organized group, they chose the image of Abejas (bees) to “symbolize [their] collective identity and actions directed toward the defense of the rights of the little ones and toward sharing the fruit of [their] work equally with everyone” (Interview 26). At the head of the organization there is the Queen, which is identified by some with Nuestra Señora de Cancuc, an indigenous face of the Virgin Mary, similar to the Virgen of Guadalupe (Interview 25).2 The image of the bees makes them all members of the organization equal as “workers for the kingdom of justice, love and peace” (Interview 26). Also, as bees use antennas for communication, Las Abejas “make an effort to keep the whole community well informed and in network with each other” (Interview 35) Like bees, they work as a collective movement. And like the little insects that fly around a variety of flowers, their religious worldview is inclusive of Catholic, Presbyterian and Mayan traditionalist identities (ibid). They explain the choice of their name in this way:

We called ourselves Las Abejas because we are a multitude able to mobilize together, as we did in Tzajalchen on December 9, 1992. Like the bees we want to build our houses together, to collectively work and enjoy the fruit of our work. We want to produce ‘honey’ but also to share with anyone who needs it. We are all together like the bees, in the same house, and we walk with our Queen, which is the Kingdom of God. We know that, like the little bees, the work is slow but the result is sure because it is collective (Interview 21).

Some other members identify their iconographic image of the bees with their political intent and active resistance against the government:

The bee is a very small insect that is able to move a sleeping cow when it pricks. Our struggle is like a bee that pricks, this is our resistance, but it’s non-violent. We do this because we need to defend who we are… we need to live as people” (Interview 22).

Since their formation, Las Abejas have experienced persecution and assassinations. At the end of a constitutional meeting in Tzajalchen, the newly formed organization was assaulted by the coalition of people directed by Augustín Hernandez Lopez. Three people were seriously wounded and one, Vicente Gutiérrez Hernandez, the municipal agent of Tzajalchen, was killed. The inhabitants of the community contacted the municipal authorities in the Chenalhó cabesera by radio and asked them to help transport the wounded to the hospital in San Cristóbal. The PRI affiliated municipal president, Antonio Perez Vázquez, responded to the community in the middle of the night, asking them to bring the bodies down to Canolal where an ambulance would transport the wounded people. Those who presided over the meeting in Tzajalchen managed to transport the victims of the assault down the roadless mountain to meet the ambulance on the main road. But when they arrived, the municipal president, having a list of names of the organizers of the meeting in Tzajalchen, ordered the arrest of those leaders who were also carrying the injured people. Felipe Hernandez Perez, Mariano Perez Vázquez, Sebastian Perez Vázquez and Manuel Perez Gutiérrez were detained without order of apprehension and transported to the jail of San Cristóbal de Las Casas (Hidalgo 1998, 58).

In addition to this clearly unjust action by the authorities, tension in the municipality of Chenalhó increased as State’s Attorney General Rafael Gonzales Lastra informed them that the five people detained, along with the other twenty eight leaders of the newly organized Las Abejas, were responsible for the attack in Tzajalchen. Twenty-eight new orders of apprehension were issued against them while the community of Tzajalchen was threatened with new intimidation against the spouses of the wounded people. This included Catarina Arias Perez, seven months pregnant from a rape carried out by one of Augustín Hernandez Lopez’s men. On December 21, 1992, exasperated by this unsustainable situation of injustice and terror, approximately 1,500 indigenous participated in a protest march from Yabteclum to San Cristóbal de Las Casas (Interview 26). For the first time, inhabitants and tourists of San Cristóbal saw the nonviolent protest of an indigenous organization called Las Abejas. For five days, Las Abejas exhibited banners in the cathedral square decrying the injustice of the government and asked for the liberation of their companions. They marched for five days from the cathedral to the jail, until the sixth day when numerous indigenous from the communities of Simojovel, San Andrés Larrainzar, Chalchiuitán and Pantelhó joined their efforts. Observing the increasing attention, the state’s attorney preferred to liberate the five incarcerated people “due to the disappearance of evidence” (Hidalgo 1998, 58). In the following years, Las Abejas continued organizing as the opposition between Priistas and Zapatistas emerged.

ON THE VIOLENT PATH TO ACTEAL

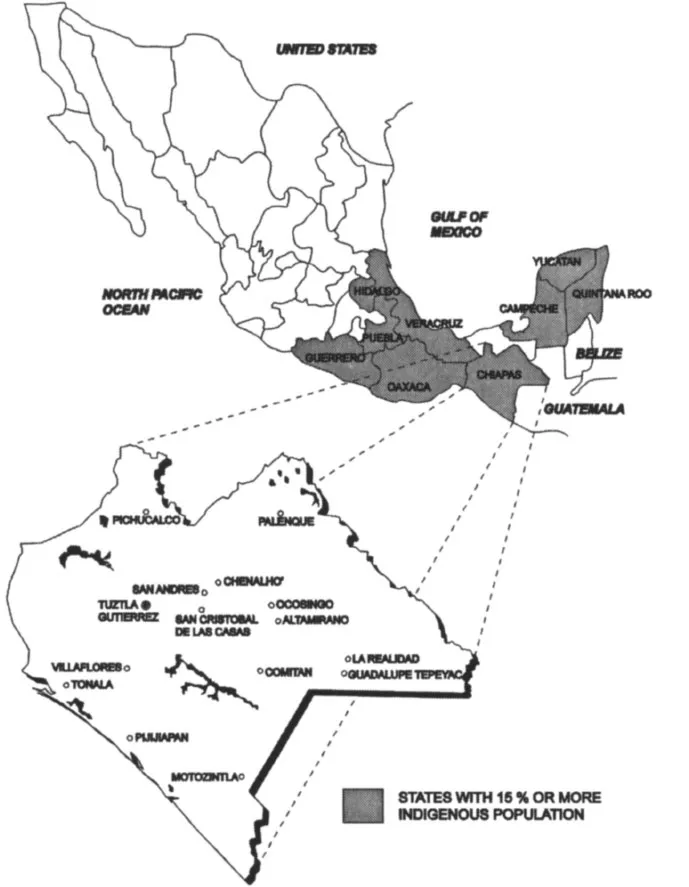

Map 1.1: Chiapas and the Indigenous Mexico

(Source: Adapted from CIACH, CONPAZ, SIPRO 1997)

With the April 1996 constitution of the Zapatista base de apoyo (support base) of Polhó, tensions significantly heightened in the Chenalhó municipality.3 Polhó is one of the EZLN autonomous communities characterized by its own government. Their goal was to solidify the right of indigenous autonomy, stipulated in the 1996 San Andres Peace Accords (Rivera Gomez 1999). In the enthusiastic climate created by the signed accords between the EZLN and the Mexican government, several other indigenous autonomous communities were created throughout the northeast of Chiapas. The government, however, never recognized the legitimacy of such communities and tried, on a few occasions, to dismantle their self-government (Hirales Morán 1998 20–23). Two months after the signing of the San Andrés Accords, the autonomous municipality of Polhó was established, comprising 42 of the 97 communities in Chenalhó.4 Polhó is also in coordination with eleven other autonomous municipalities present in the Highlands and remains in contact with others in the Lacandon and northern regions of Chiapas.

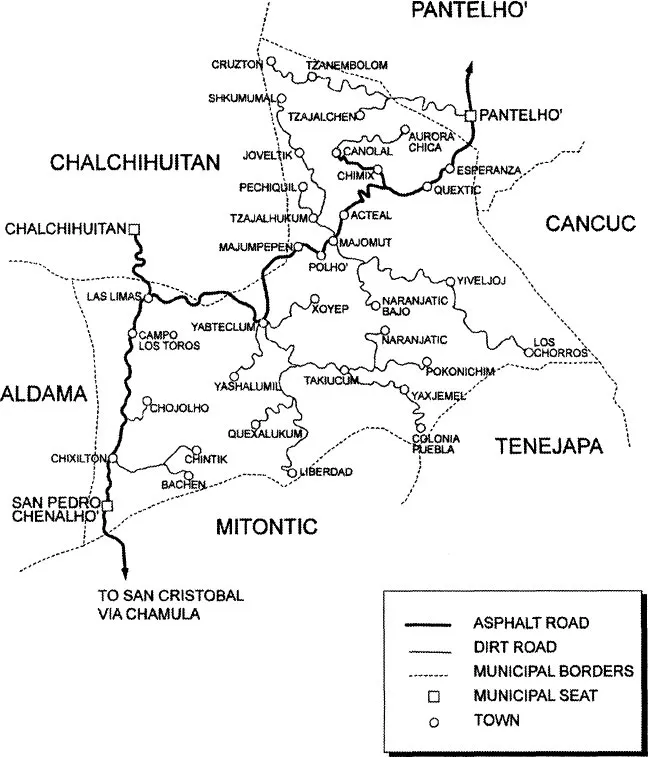

Map 1.2: The Chenalhó Municipality

(Source: Adapted from COCOPA 1998)

Since the beginning of the EZLN rebellion in 1994, Las Abejas was pressured by both PRI communities and the autonomous municipality of Polhó to join their sides. The support of a very large organization like Las Abejas was important for both sides of the conflict (Hernández Navarro 1998 7–10). The pressures began to intensify with the Zapatista invasion of the banco de arena (sand mine) in Majomut. The banco de arena is a small gravel and sand mine visible on the left side of the road between Polhó and Acteal. The revenue coming from the sale of gravel and sand used to pave the road from Chenalhó to Pantelhó benefited a PRI peasant organization supported by the government until August 16, 1996. On that day, the autonomous municipality declared this precious piece of land under EZLN jurisdiction. The autónomos earned money from it until March 1997, when the paving project of the road was completed (Hirales Morán 1998, 25). Clearly, the invasion of the banco de arena provoked the irritation of Priistas from Majomut and Pechequil and Cardenistas from Los Chorros, who previously benefited from it.

On September 23, 1996, disturbed by continuous threats and pressures from the Priistas, Las Abejas co-signed a letter with the Zapatista Autonomous Council of Polhó to the Governor of Chiapas, Julio César Ruiz Ferro. From then on, most PRI communities linked Las Abejas with the autónomos Zapatistas, and indiscriminately targeted them in a series of ambushes, reprisals and murders that eventually culminated in the Acteal massacre. In fact, during the time between September 1996 and December 1997 eighteen people affiliated with the PRI and twenty-four people affiliated with the Zapatistas were killed in the Chenalhó municipality. Several others were wounded. (Interview 42 and 66).

Las Abejas leaders attempted to establish dialogue between the two sides on several occasions (Hirales Morán 1998). However, the pacts emerging from these dialogues were soon broken as both sides began expelling Zapatista or Priista families from their communities. Most of the displaced families of Las Abejas who found refuge in Acteal were expelled from the communities of La Esperanza, Tzajalucum and Queshtic. A few families arrived in Acteal the nights of December 17 and 18, 1997, escaping the esca...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- SERIES EDITORS’ FOREWORD

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

- CHAPTER ONE Las Abejas and the Acteal Massacre

- CHAPTER TWO Methodological and Theoretical Frameworks

- CHAPTER THREE The Struggle for Land and Dignity in Chiapas

- CHAPTER FOUR The Juxtaposed Meanings of Acteal

- CHAPTER FIVE The Cultural and Religious Frameworks of Las Abejas

- CHAPTER SIX The Political and Human Rights Frameworks of Las Abejas

- CHAPTER SEVEN Las Abejas’ Construction of Nonviolent Resistance

- CHAPTER EIGHT Las Abejas’ Syncretic Identity of Resistance

- GLOSSARY

- NOTES

- REFERENCES

- INDEX