- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Universal Grammar

About this book

This collection of 15 articles reflects Edward Keenan's long-standing research interests in the comparative syntax of the languages of the world. It includes two seminal 'foundation' articles, Noun Phrase Accessibility and Universal Grammar (with Bernard Comrie) and Towards a Universal Definition of 'Subject of'. Most of the other articles have appeared in a variety of relatively inaccessible places, and so this book brings together for the first time a large body of work supporting the research directions taken in the foundation articles. In addition, one article of a psycholinguistic sort was specially prepared for this volume.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE:

CROSS LANGUAGE VARIATION

This section includes one of the foundation articles mentioned in the Introduction, ‘Noun Phrase Accessibility’, written with Bernard Comrie in 1977. It introduces the Accessibility Hierarchy, which has proved to be of some utility in later studies in Universal Grammar, as well as in psycholinguistic and second-language-learning literature. The less well-known article here, ‘Variation in Universal Grammar’, is an extensive text study which supports the hypothesis that the Accessibility Hierarchy can be used as a measure of stylistic complexity. The remaining article in this section, ‘The Psychological Validity of the Accessibility Hierarchy’ (written with Sarah Hawkins), reports the results of a series of psycholinguistic experiments designed broadly to test the hypothesis that the Accessibility Hierarchy can be used as a measure of the cognitive complexity of relative clauses.

1 | NOUN PHRASE ACCESSIBILITY AND UNIVERSAL GRAMMAR1 |

In section 1 we present the Accessibility Hierarchy, in terms of which we state three universal constraints on Relative Clause Formation. In addition, we present the data in support of these constraints and discuss certain partial counterexamples. In section 2 we propose a partial explanation for the hierarchy constraints and present further data from Relative Clause Formation supporting these explanations. Finally, in section 3 we refer briefly to other work suggesting that the distribution of advancement processes such as Passive can be described in terms of the Accessibility Hierarchy; these facts show that the proposed explanation for the Hierarchy needs to be generalised.

1. The Accessibility Hierarchy

1.1 Two Methodological Preliminaries

We are attempting to determine the universal properties of relative clauses (RCs) by comparing their syntactic form in a large number of languages. To do this it is necessary to have a largely syntax-free way of identifying RCs in an arbitrary language.

Our solution to this problem is to use an essentially semantically based definition of RC. We consider any syntactic object to be an RC if it specifies a set of objects (perhaps a one-member set) in two steps: a larger set is specified, called the domain of relativisation, and then restricted to some subset of which a certain sentence, the restricting sentence, is true.2 The domain of relativisation is expressed in surface structure by the head NP, and the restricting sentence by the restricting clause, which may look more or less like a surface sentence depending on the language.

For example, in the relative clause the girl (that) John likes the domain of relativisation is the set of girls and the head NP is girl. The restricting sentence is John likes her and the restricting clause is (that) John likes. Clearly, for an object to be correctly referred to by the girl that John likes, the object must be in the domain of relativisation and the restricting sentence must be true of it. We shall refer to the NP in the restricting sentence that is coreferential with the head NP as the NP relativised on (NPrel); in our example, this is her, i.e. the direct object of John likes her.

Note that we only consider definite restrictive RCs in this study. The role of the determiner the is held constant and ignored, and the term RC is used to apply to the collocation of the head NP and the restricting clause.

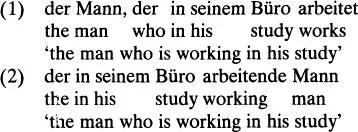

Note further that our semantically based notion of RC justifies considering as RCs certain constructions that would perhaps not have been so considered in traditional grammar. Thus, in German, alongside the traditional RC in (1) we also count the participial construction in (2):

As the German data above illustrate, not only do different languages vary with respect to the way RCs are formed, but also within a given language there is often more than one distinct type of RC. We shall refer to distinct ways of forming RCs as different relative-clause-forming strategies. Different strategies differ with regard to which NP positions they can relativise. Thus, the participial strategy in (2) above can only relativise subjects (that is, the head NP can only be understood to function as the subject of the main verb of the restricting clause), whereas the strategy in (1) above functions to relativise almost any major NP position in simplex sentences. Consequently, generalisations concerning the relativisability of different NPs must be made dependent on the strategies used. It will be critical therefore to provide some principled basis for deciding when two different RCs have been formed with different strategies.

There are many ways RCs differ at the surface, and hence many possible criteria for determining when two strategies are different. We have chosen two criteria that seem to us most directly related to our perception of how we understand the meaning of the RC — that is, of how we understand what properties an object must have to be correctly referred to by the RC. The first concerns the way the head NP and the restricting clause are distinguished at the surface, and the second concerns how the position relativised is indicated.

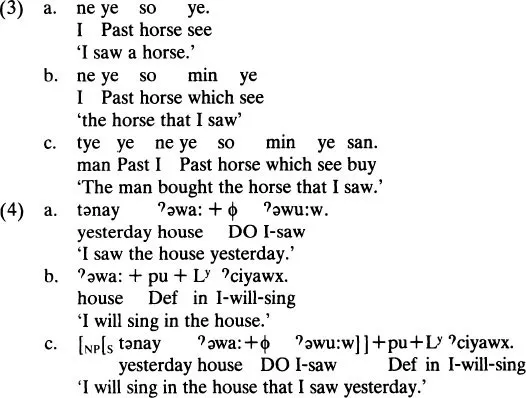

In the first case we consider two RCs to be formed by different strategies if the relative position of the head NP and the restricting clause differs. There are three possibilities: the head occurs to the left of the restricting clause, as in (1) above (postnominal RC strategy); the head occurs to the right, as in (2) (prenominal RC strategy); or the head occurs within the restricting clause (internal RC strategy), as in (3) and (4), from Bambara (Bird 1966) and Digueño (Gorbet 1972), respectively:

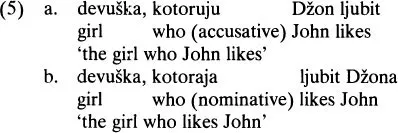

In the second case we consider two RCs to be formed from different strategies if one presents a nominal element in the restricting clause that unequivocally expresses which NP position is being relativised, and thus we know exactly what the restricting clause is saying about the head NP (that is, we can recover the restricting sentence from surface) (+case RC strategy). For example, the English strategy that forms the girl who John likes is not case-coding since who, the only relevant particle in the restricting clause, can be used as well if the role of the head NP in the restricting clause is different, e.g. the girl who likes John (—case RC strategy). On the other hand, in comparable sentences is Russian, (5a) and (5b), the form of the relative pronoun does unequivocally tell us the role of the head NP, so that strategy in Russian is case-coding:

Note, however that RCs in English like the chest in which John put the money are considered case-coding, since the preposition in, which indicates the role of the head NP, is present in the restricting clause.

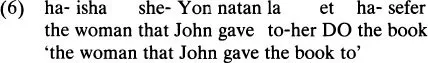

In addition to the use of relative pronouns, case can be coded in another way in the languages covered in our study. Namely, a personal pronoun can be present in the NP position relativised, as in Hebrew:

1.2 The Accessibility Hierarchy and the Hierarchy Constraints

1.2.1 Statement of the Hierarchy and the Constraints. On the basis of data from about fifty languages, we argue that languages vary with respect to which NP positions can be relativised, and that the variation is not random. Rather, the relativisability of certain positions is dependent on that of others, and these dependencies are, we claim, universal. The Accessibility Hierarchy (AH) below expresses the relative accessibility to relativisation of NP positions in simplex main clauses.

Accessibility Hierarchy (AH)

SU > DO > IO > OBL > GEN > OCOMP

Here, ‘>’ means ‘is more accessible than’; SU stands for ‘subject’, DO for ‘direct object’, IO for ‘indirect object’, OBL for ‘major oblique case NP’ (we intend here NPs that express arguments of the main predicate, as the chest in John put the money in the chest rather than ones having a more adverbial function like Chicago in John lives in Chicago or that day in John left on that day), GEN stands for ‘genitive’ (or ‘possessor’) NP, e.g. the man in John took the man’s hat, and OCOMP stands for ‘object of comparison’, e.g. the man in John is taller than the man.

The positions on the AH are to be understood as specifying a set of possible grammatical distinctions that a language may make. We are not claiming that any given language necessarily distinguishes all these categories, either in terms of RC formation or in terms of other syntactic processes. For example, some languages (e.g. Hindi) treat objects of comparison like ordinary objects of prepositions or postpositions. In such cases we treat these NPs as ordinary OBLs, and the OCOMP position on the AH is unrealised. Similarly, in Gary and Keenan (1976) it is argued that the DO and IO positions are not syntactically distinguished in Kinyarwanda, a Bantu language. Further, it is possible that in some language RC formation might distinguish between two types of DOs. If this were so, we would like to expand the AH at that point and say that languages like English do not make the distinction. For the moment, however, we take the AH as specifying the set of possible grammatical distinctions to which RC formation (from simplex main clauses) may be sensitive, since our data do not appear to justify any further refinement in the categories.

In terms of the AH we now give the Hierarchy Constraints (HCs):

The Hierarchy Constraints (HCs)

1. A language must be able to relativise subjects.

2. Any RC-forming strategy must apply to a continuous segment of the AH.

3. Strategies that apply at one point of the AH may in principle cease to apply at any lower point.

The HCs define conditions that any grammar of a human language must meet. HC1 says that the grammar must be designed to allow relativisation on subjects, the uppermost end of the AH. Thus, for example, no language can relativise only DOs, or only locatives. It is possible, however, for a language to allow relativisation only on subjects (and this possibility is in fact realised: see 1.3.1 for examples). HC2 states that, as far as relativisation is concerned, a language is free to treat adjacent positions on the AH as the same, but it cannot ‘skip’ positions. Thus, if a given strategy can apply to both subjects and locatives, it can also apply to DOs and IOs. And HC3 states that each point of the AH is a possible cut-off point for any strategy that applies to a higher point. This means that in designing the grammar for a possible human language, once we have given it a strategy that applies at some point on the AH, we are free to terminate its application a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Half Title Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Contents

- References for the Articles

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Part One: Cross Language Variation

- Part Two: Grammatical Relations

- Part Three: Relation-Changing Rules in Universal Grammar

- Part Four: Explanation in Universal Grammar

- Part Five: Semantics in Universal Grammar

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Universal Grammar by Edward L. Keenan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.