![]()

II

Microfinance in South Asia

![]()

3

Bangladesh: The Pioneering Country

Iftekhar Hossain, Javed Sakhawat, Ben Quiñones and Stuart Rutherford

Introduction

Bangladesh is the cradle of microfinance. If necessity is indeed the mother of invention, then this may not be surprising. The need was great in Bangladesh when the new nation arose three decades ago, from the ashes of political and civil unrest between West and East Pakistan, as one of the world’s poorest countries with the least developed finance sectors. The microfinance providers of Bangladesh can be rightfully proud of leading the world in reaching the poor. The success of Grameen Bank, the availability of large number of NGOs formed after liberation of the country in 1971, and pressure on the NGOs to be less dependent on donors have all contributed to this success.

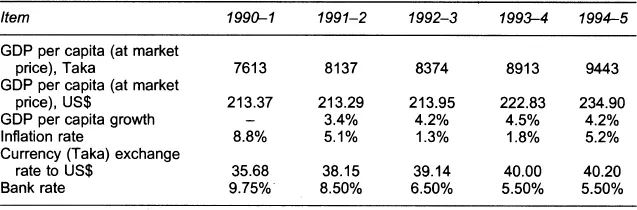

Despite chronic political instability, Bangladesh has not fostered a grossly hostile environment for the MFIs. The Bangladesh economy has steadily grown during the last 25 years at a rate considered to be ‘moderate’ by Asian standards, with the average annual growth rate of GDP hovering around 4.2 per cent during the period 1970–94. There has been no hyperinflation to contend with in the 25 years since Independence. Rather, a steady decline in the international value of the Taka has allowed MFIs to get ever more value, in local terms, out of the hard currency grants given them by donors. The relatively low inflation rate has also contributed to the lowering of interest rates from 9.75 per cent in 1990–1 to 5.50 per cent in 1994–5 (Table 3.1).

Although population growth has been falling through the years, and currently stands at 2.2 per cent p.a., in absolute terms the population of Bangladesh has almost doubled since Independence to 120 million in 1996, and it is forecasted to again double in the next twenty years to reach 250 million by the year 2015. Some 50 million Bangladeshis remain in absolute poverty, half of them ‘hard-core’ poor. Poverty is defined in terms of the required per capita daily caloric intake of less than 2122 for absolute poverty and less than 1805 for hard-core poverty. Although this definition is the most commonly used, there is increasing recognition of the need to measure the index of human development which includes other factors affecting the quality of life of the people such as nutrition, health and sanitation, housing, personal security, access to state distribution system, participation and institutional capability, and crisis-coping capacity.

Table 3.1: Selected Macroeconomic Indicators for Bangladesh, 1990–5

Source: Iftekhar Hossain and Javed Sakhawat, 1996.

The majority of Bangladesh’s population (80 per cent) continues to live in rural areas where the rice harvest has grown to keep pace with population growth. But rice yields per hectare have stagnated and despite a shift away from agriculture in the composition of rural incomes there is little evidence yet of the development of rural industry on any scale. Decreasing availability of farming land and the lack of rural employment opportunities have fuelled urban migration. The fairly high incidence of urban poverty indicates the likelihood of a transfer of rural poverty to the towns resulting from the migration of the rural destitute in search of work in the urban areas. In the towns, the ready-made garments industry sprang into life in the 1980s and is now the country’s biggest source of hard currency earnings. This has been accompanied by a quickening of the growth rate of the urban population, and attention is turning increasingly to the problems of urban poverty.

Poverty Alleviation Policies and Programmes

The Fourth Five Year Plan (1990–5) of the government of Bangladesh explicitly emphasized the importance of poverty reduction and employment generation. It has vigorously supported social safety net programmes such as Food For Work (FFW), Vulnerable Group Development (VGD) and the Rural Maintenance Programme (RMP) to deal with the problem of poverty, sometimes in close collaboration with NGOs. However, these programmes have had limited coverage and the foodstuff distributed under the FFW and VGD actually declined in recent years.

The government has attempted to use the co-operative model developed at the Bangladesh Academy of Rural Development at Comilla as the basis for a nationwide credit programme for small and landless farmers. This programme fell into difficulties but is now being revived with group-based lending technology borrowed from Grameen Bank. (A successful example is the BRDB’s Rural Development Project 12 (RDP-12), one of the case studies.) Starting with a series of experiments in the 1970s facilitated by the USAID and known as the Rural Finance Experimental Project (RFEP), government-owned banks have also been encouraged to test many innovative approaches to rural credit. None of these efforts proved as successful as that of Grameen Bank, which started in 1976 as a private experiment by Professor Muhammad Yunus, then linked up with a government-owned bank and finally, with Central Bank support, obtained its own unique ordinance as a ‘bank for the poor’ in 1983.

More recently, the government has set up the PKSF, with Professor Yunus on its board, which provides low-cost funds to more than a hundred NGO partners with poverty-targeted credit programmes. It will soon receive about $120 million from the World Bank on International Development Association loan terms. The NGO Bureau, the body that exerts government control over NGOs, has for some years asked NGOs to become involved in credit for the poor. Most use Grameen-type delivery systems. Several of the larger NGOs have also been developing their own models, and the largest of these, the BRAC and the ASA, now use credit delivery methods not dissimilar to Grameen’s, though they began differently. Proshika, another big NGO (not included in our case studies), continues to promote and then lend to small neighbourhood-based savings-and-loan co-operatives, and several other NGOs follow this older model.

Financial institutions and their outreach to the poor

Public-sector institutions providing credit to priority sectors include two agricultural banks (the Bangladesh Krishi Bank and the Rashaji Krishi Unnayan Bank), the Bangladesh Rural Development Board (BRDB) with its various Rural Development Projects (RDP-12, RDP-9, RDP-5, etc.), and government line agencies operating their respective credit programmes for specific target groups. Government-owned banks still have by far the largest share of formal bank branches in the country. In addition to these public-sector institutions, three nationalized commercial banks (Agrani, Janata and Sonali) have also traditionally been directed by the government to lend to priority sectors, including poor households and women. Having been used extensively by the government as delivery channels for its subsidized credit programmes, these banks have fallen into disarray: they are technically bankrupt, deliver less rural credit than Grameen and the NGOs, and have not managed to raise the country’s domestic savings rate above a measly 8 per cent of GDP. Despite continuous prodding by donors, the government is still undecided about what to do with them.

Complementing the efforts of the government are member-based MFIs, including Grameen Bank, the ASA, Proshika, the BRAC, co-operatives, and NGOs estimated to be around 200. A recent World Bank report on rural finance estimates that a little over 5 per cent of rural households are being serviced annually by public-sector institutions and 25 per cent by member-based institutions.

At the other end of the scale, and especially in the towns, there are an infinite number of informal user-owned savings intermediation clubs such as RoSCAs and annual savings clubs. They are reliable, innovative and growing fast, but have yet been little noticed.

Financial Policy Environment

The ‘invisibility’ of the NGO-MFI sector to the formal regulators has, so far, largely worked to the advantage of MFIs in Bangladesh. It has allowed them to charge high rates of interest on loans – a factor that has been crucial to the growth of the bigger MFIs. It has also allowed them to set their own rules. The ASA, for example, does not have to worry about formal liquidity ratios when it lends out its customers’ savings. It has allowed them almost unrestricted access to donors, and has allowed them the freedom to develop their own special market and to learn as they grow. It is not surprising therefore, that until very recently the general mood among MFI practitioners, as far as regulation was concerned, was to let sleeping dogs lie’. Things may now be changing.

It is probably merely a matter of time before MFIs come under the scrutiny of a more formal supervisory body of some sort – the Central Bank, Ministry of Finance, or some special new second-tier regulatory body. Several trends will ensure this: (1) The very growth of the MFIs brings them every day more to the attention of the authorities and of the big donors. (2) The continuing decline of the government-owned rural banks makes MFIs look ever more like the nation’s main banking instrument in the countryside – one donor has contemplated the total demise of the formal banking sector and the spread of MFIs to every sub-district. (3) International attitudes – expressed not least at the Bank Poor ’96 Regional Workshop in Kuala Lumpur – are turning in favour of a formal status for MFIs, and Bangladesh’s MFIs are now much more aware of international trends than they were three or four years ago. Finally, (4), as MFIs think about mobilizing more savings from the general public the need for formal protection of savings grows stronger.

Indeed, there have already been several instances of rogue or simply incompetent MFIs going out of business at the expense of poor rural savers, but because this is a new discussion in Bangladesh it is not at all clear what form the regulation might take. There are, however, still many ways of delivering financial services to the poor that have simply not yet been thought about or tried. For instance, there are no rural shareholder banks, or district-level private banks, nor has there been much innovation in thrift co-operative (or credit union) management. In addition, no one has seriously tried to link the growing number of spontaneous user-owned savings clubs together.

Microfinance Capacity Assessment

To assess the breadth and depth of microfinance outreach in Bangladesh, eight MFIs were selected for in-depth case study. Table 3.2 gives a brief description of the eight sample MFIs: Grameen Bank, the BRAC, Rural D...