- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Accounting Theory

About this book

Discussing various aspects of accounting theory by collecting diverse pieces originally published between 1978 and 1994, this volume asks and answers the following questions:

- What do the figures from a company's report actually mean?

- To what uses can they properly be put?

- Could they be improved?

- What effect have they on the outside world?

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

DEPRECIATING ASSETS

Contents

Foreword

Preface

1 The Problem

2 Concepts and Definitions

3 Choosing Optimum Life

4 Patterns of Value and Cost

A. The Traditional Methods

B. Deprival Value and Depreciation

C. Testing the Traditional Methods

D. Interest

5 Revaluation

A. Inflation

B. Specific Price-change

C. Combined General and Specific Price-change

6 Index

Preface

You will have noticed that depreciation often plays a big part in accounts. A balance sheet is likely to include machines, etc; it usually shows them at their cost when new, and then deducts the total depreciation that has been written off since their acquisition. And the income statement includes in its costs the current year’s addition to that total.

Thus everyone who looks at accounts – investors, managers, bankers, students, and so on – should have some idea of how depreciation is calculated. What do the asset values and the costs mean? Depreciation measures can have a great effect on a company’s results, yet they are chosen from a wide range of possible figures, by rules that are vague and little understood.

This monograph tries to explain the accountant’s methods of dealing with depreciation and to suggest ways of testing these methods. But it is too short to cover all sides of its complex subject: you will have to read further to get a full view. You will gain much by so doing. For depreciation is beset by interesting problems, some of which are linked with lively controversies (eg, over inflation accounting). In what follows I must sometimes take sides in these controversies; however, when I do so, I try to point out that there are other views.

The monograph has five chapters. The first four sketch the framework, and attempt to establish logical rules for measuring depreciation in times when prices are stable. The fifth asks how these rules should be amended when prices change.

Earlier drafts have been read by the group that manages this series of publications for the Scottish Institute – Professors D. Flint and A.M. McCosh, Mr. P.N. McMonnies and Professor D.P. Tweedie; and also by Miss Winifred Elliott and Mrs Paula Walker. Their criticism was invaluable, and I am grateful.

1 The Problem

Final accounts usually cover a year. So they would be easy to draft if the firm’s happenings all came to a neat full-stop by the year-end – in particular if the firm could get all its inputs (goods and services) in doses that were used up exactly by then.

But a firm in fact buys inputs in doses that straddle business years: at the year-end its wealth thus includes sources of future inputs, such as stores not yet consumed, rent prepaid and machines that will still give service. The accountant must value these assets in his balance sheet. Likewise he must value the part of each asset that became input during the year and include this cost in the income statement. You will face the same problem if you keep monthly accounts, and have three-month season tickets or three-weekly haircuts.

The accountant’s task may not be hard where the number of remaining input units can be checked physically and where the value per unit can be readily found. Thus stores-on-hand can be listed as so many tons or gallons, each worth so much money; and prepaid rent can be valued at so much per remaining month. Minerals (gravel-pits, oil-wells, etc) are less easy: experts may, or may not, know how many physical units are left; unit-values may or may not be well known and should presumably be trimmed to allow for, eg, increasing extraction costs as veins peter out.

Assets such as machines are a much worse problem. It is hard enough to define their invisible service-units, let alone estimate the residual number. And how do we find the value of each unit, especially if the asset will in future years grow less useful and need more repairs? It is mainly these difficulties that distinguish depreciating assets from the others.

Depreciating assets viewed as stores bought in bulk

Despite the greater difficulty of measuring and valuing the service-units of depreciating assets, the relevant principles seem much the same as for other sources of input such as stocks and stores. (And it should not matter, surely, that the balance sheet classes machines as “fixed assets” and stocks as “current”.)

Our understanding of depreciation will in fact be greatly helped if we look on a depreciating asset in this light. We can imagine a firm that decides to buy stores (say, oil for heating) in bulk, because bulk-buying gives a lower unit-price and extra security and convenience. The oil is then consumed during more than one year; and accounting has evolved fairly adequate rules for charging each year with its usage and for valuing the residue at each year-end. Likewise the firm may choose to buy a machine with a long life because it is a better source of inputs, rather than buy a series of second-hand machines with shorter remaining lives or rent a machine by the month. The analogy with stores is thus close and should help us to devise rules for measuring depreciation.

The problem in diagram form

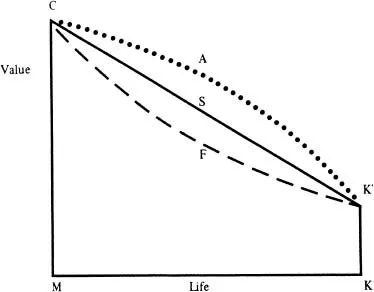

You may find that Diagrams 1 and 2 help you to see the problem. They illustrate the twin aspects of the asset’s life-story: Diagram 1 traces its dwindling value over its life-span, ie, its value “pattern” or “profile”; Diagram 2 shows the fall in value during each year, ie, the yearly depreciation cost.

1. Asset value patterns

MC is the cost of acquiring the asset. KK’ is its final re-sale price (“salvage” or “scrap” value). MK is its life-span.

At the date of “birth”, M, usually the only known figure is the price MC. The accountant can only guess how long the life MK will stretch and what the scrap proceeds KK’ will be (though past experience with like assets may help his guessing). And what sort of path does the value curve CK’ follow during the life?

The diagram suggests three of these possible value patterns between C and K’. They reflect three of the traditional accounting methods for writing off depreciation:

Diagram 1 Asset Value Patterns

(1) | CSK’ (unbroken line), found by the straight line method. |

(2) | CAK’ (dotted line), a “humped” curve, found by the annuity method (which allows for “interest” or “cost of capital”). |

(3) | CFK’ (broken line) a “sagging” curve, found by the clumsily-named fixed percentage of the diminishing balance method. Most of the other popular methods also give sagging curves.1 |

The choice of curve can make a vast difference to the balance sheet figures, and to the value fall that must be written off each year.

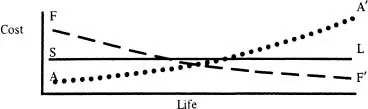

2. Yearly write-off patterns

Diagram 2 shows three of the possible patterns of yearly write-offs (depreciation charges to successive income statements over the asset’s life), namely those reflecting the three value patterns of Diagram 1. (For clarity, the vertical scale of Diagram 2 is exaggerated.)

Diagram 2 Yearly Depreciation Costs

(1) | The horizontal SL shows constant yearly costs (ie, the constant value falls of CSK’ above). It thus shows the depreciation charges of the straight-line method. |

2) | The upward sloping AA’ shows costs that are low at the start but grow each year (ie, the increasing value falls of CAK’ above). It thus shows the net charges by the annuity method. This tilted pattern can be described as “low-high”. |

3) | The downward-sloping FF’ shows costs that are high at the start but shrink each year (ie, the diminishing value falls of CFK’ above). It thus shows the charges by the fixed percentage method. This pattern can be described as “high-low”. |

Our task is to ask ourselves which of the traditional book-keeping methods – the three illustrated above and some four others – best fits the circumstances of a given asset. And we may well ask, too, whether some quite different type of cost curve – say, one with much higher early charges – would not fit better; or whether we should not devise a special curve for each asset, instead of clinging to stereotypes.

Importance of using the best method

Even though the various methods all aim to write off...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- WHAT IS WEALTH?—Nursemaid versus Accountant (Edinburgh: The Accountants Magazine, May 1978)

- ASSET AND LIABILITY VALUES (London: Accountancy, April 1994)

- ASSET VALUES—Goodwill and Brand Names (London: Reprint of Occasional Research Paper 14 of the Chartered Association of Certified Accountants, 1993)

- WHAT IF THE PARTS EXCEED THE WHOLE?—Assets versus the Firm’s Value

- “GOODWILL”—The Misconceived Asset (London: The Times, Dec. 7, 1992)

- THE FUTURE OF COMPANY REPORTING (Oxford: Philip Allan, Developments in Financial Reporting, ed. T. A. Lee 1981)

- INCOME—A Will-o’-the Wisp? (London: Van Nostrand Reinhold, Accounts, Accounting and Accountability, eds. G. MacDonald and B. A. Rutherford, 1989)

- REALISATION—A Wavering Rule (London: Accountancy, July 1992)

- EARLY CRITICS OF COSTING—LSE in the 1930s (Harrisonburg, Va., The Academy of Accounting Historians, The Costing Heritage, ed. O. F. Graves, 1991)

- DEPRECIATING ASSETS (Edinburgh, reprinted from a series published by the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland, 1980)

- DEPRECIATION, REPLACEMENT PRICE, AND COST OF CAPITAL. With N. H. Carrier (Chicago: Journal of Accounting Research, Autumn 1981)

- DEPRECIATION AND PROBABILITY. With P. Watson (London: LSE Foundation, External Financial Reporting, eds. B. Carsberg and S. Dev, 1984)

- DISCOUNT AND BUDGETS—With Constant Prices and Inflation (London: reprinted from publications of the Chartered Association of Certified Accountants, 1986)

- ACCOUNTING RESEARCH—Academic Trends versus Practical Needs (Edinburgh: reprinted from series published by the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland, 1988)

- ACCOUNTING STANDARDS—Boon or Curse? (London: Accounting and Business Research, Winter 1981)

- EARLY ACCOUNTING: The Tally and The Checker-Board (Oxford: Clarendon Press, Accounting History, eds. R.H. Parker and B.S. Yamey, 1994)

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Accounting Theory by William Baxter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Accounting. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.