![]()

Music in the Fifteenth-Century Printed Missal

MARY KAY DUGGAN

The introduction of hundreds of exactly replicated copies of the missal, the liturgical book of texts and chant for the celebrant of the Catholic Mass, affected the very nature of the service book and the plain chant it contained. The move to print the liturgy was accompanied by a complex web of technological, liturgical and political challenges that provoked reaction by printers and publishers, local and regional monastic and diocesan editors, and the very top echelons of monastic orders, ecclesiastical provinces, and the papacy. Missals form a large percentage of the corpus of early printed music put into the hands of fifteenth-century readers. Apparently well aware of the significance of the appearance of liturgical books in print, contemporary liturgical reform movements were intensely involved in the process of editorial revision and the production of corrected copy texts for the printers. The books themselves illustrate the manner in which printers responded to the challenges of transferring newly reformed manuscripts into print, through the design of layout, regional styles of chant, size relationship of music type to letter type in the absence of ruling, musica ficta, color for staves, complex melismatic neumes, liquescence, and mensural chant. From the first decades the publication of liturgical music displayed the characteristics of centralized and specialized production together with widespread distribution networks that were to contribute to the standardization of liturgical books and culminate after the Council of Trent in the next century in a monopoly by a single publisher appointed by Rome.

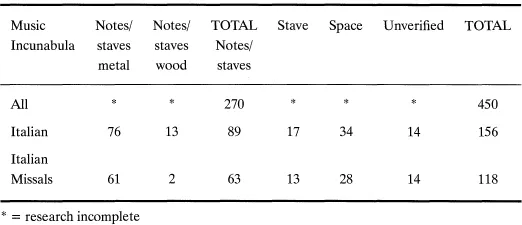

Music incunabula are usually defined as those books printed before 1501 containing music in the form of printed notes and staves, printed notes or staves, or printed text with space allocated by the printer for the addition of notes and staves by hand.1 Current estimates suggest that some four hundred and fifty editions of a total of about 30,000 incunabula satisfy that definition of music incunabula; about 270 contain printed notes and staves.2 Detailed study of 156 Italian music incunabula shows that most were printed with notes and staves from metal type, though in the earliest period of printing before such type was available a significant number were printed with space for music: 76 contain notes and staves printed from metal, 13 contain notes and staves printed from wood, 17 contain printed staves, 34 have space allocated for music, and fourteen are titles for which no copy could be located or examined (see Table 1). Of 156 Italian music incunabula, 75% or 118 are missals;3 an additional five missals4 printed in Italy contain no music or space for music, though some owners inserted manuscript music on extra leaves bound in. A higher number of editions of the missal, 191, were printed in what incunabulists call German-speaking lands (the area covered today by Germany, Austria, Switzerland and parts of Eastern Europe).5 Estimating that each of the Italian and German editions was issued in five hundred copies (the number of copies ordered, for examples by Abbot Udalricus III of the Benedictine Monastery of Michelsberg in Bamberg of the 1481 Missale benedictinum (Bamberg: Johann Sensenschmidt; H 1127), the combined total would be over 150,000 books, all but 10,000 printed between 1480 and 1500.

Table 1 A comparison of all music incunabula and Italian production.

A missal is made up of a central portion of fixed prayers, the Canon, preceded by the readings for Sundays (Temporale) to Easter and followed by the Sundays after Easter and the readings for feast days (Sanctorale). The text of sung portions is written in smaller letters than those read by the priest or celebrant. Music notation is included for those portions sung by the celebrant, including a number of prefaces that vary according to the time of year and level of feast, the Pater noster, incipits of the chants of the Ordinary or unvarying parts of the service (Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Agnus Dei), and a few chants for Holy Week. The choir’s sung portion is contained in another liturgical book, the gradual. A calendar of feasts for the year, graded according to level of feast, is usually placed at the beginning of the missal. Unusual in the manuscript missal, preliminary material after the calendar grew in the printed missal to contain such extras as a letter from the bishop requesting those under him to purchase the book, explanation of the perpetual calendar, cautions to the priest in handling the host, prayers to be said while vesting, tables, and indexes. Titles of sections and readings, directions for the additions of sung portions (introit, psalm, antiphon, verse), and directions for actions of the priests appear in red, thus called rubrics.

Editions of fifteenth-century missals reflect prescriptions of various rites, the Roman rite being most common but others distinctive to localities (as, for example, Ambrosian to Milan, Sarum to England). One of the preoccupations of the Catholic Church councils in Constance and Basel in the first half of the fifteenth century had been monastic reform, including the development of a standard observance that could be accepted on both sides of the Alps. Benedictines at Melk in Austria, Subiaco in the Papal States, Padua in the Venetian Republic, and Bursfeld and Mainz in Germany played a major role in arguing for and developing a reformed liturgy.6 Despite conflict between conciliar and papal authority which led the Council of Basel to elect a second pope in 1441, northern reform efforts continued. In 1448 at Mainz papal legate Cardinal Juan de Carvajal, an appointee of newly elected Pope Nicolas V who promised to unite Europe again under one pope, approved the new Ordinarius divinorum of the growing Bursfeld Congregation of Benedictines and specifically mentioned for the first time the need for standardized liturgical chant melodies as well as texts.7 With Carvajal’s papal entourage in Mainz was the German Nicolas of Cusa, former Basel conciliarist and soon to be made a cardinal and papal legate himself. In the capacity of papal representative he returned to Mainz in 1451 to decide against the reformed liturgical books prepared by the Benedictine house of St. James in Mainz and, with authorization to have recourse to secular arms if need be,8 he pronounced in favor of the version prepared by the Bursfeld Congregation. The Ordinarius divinorum has been described as “really only an adaptation of the office of the Roman Curia for monastic use.”9 After joining the Bursfeld Congregation the Benedictines of St. James managed to issue their Psalter in 1459 and a Canon missae appeared in Mainz in 1458 (GW 5983), but the first printed missal was delayed until about 1472 when a Missale romanum (Goff M-643) appeared somewhere in Central Italy with an incipit attributing the editing to Franciscans, the order of the current pope Sixtus IV. Another undated missal appeared in equally obscure circumstances about 1473, a Missale speciale for the diocese of Constance. An alphabetic type similar to that of the first missal was used in Rome by Ulrich Han to print the 1475 Missale romanum (H 11364), reprinted with music in 1476 (H 11366) and often afterward by Han and his successor, both semi-official printers of papal documents. The Bursfeld Benedictines continued to negotiate as late as 1471 to print their liturgical books in Subiaco;10 the Ceremoniale and Ordinarius appeared in 1474–75 from the press of the Brothers of the Common Life in Marienthal (HC 12059, Goff O–85; H 4883 = 12059, Goff S–756) and the missal in 1481 (H 11267) printed in Bamberg by Johann Sensenschmidt with the votive Masses and sequences integral to northern liturgical tradition.11

Table 2 Missals Printed in the Fifteenth-Century in Italy and in German-speaking Lands.

Country | Roman Rite | Religious Order | Local Rite | Total |

Italy | 84 | 14 | 25 | 123 |

German-speaking | 10 | 14 | 168 | 191 |

A comparison of missals produced in Italy with those printed in Germanspeaking lands (see Table 2) reveals a scarcity of editions in the Roman rite printed in Germany; if figures were available, that scarcity would be seen to hold true for the rest of Europe. North of the Alps, missals used outside the monastery were under the editorial control of the diocese although cathedral chapters were being urged in visitations by papal legates to bring local books into closer agreement with the practices of Rome. Widespread dissemination of printed Roman missals provided editors with easy access to those practices. Proof that printed missals became the exemplars for future editions is found in a copy of the Missale romanun (Venice: G. B. Sessa, 1497, H 11412*) that contains annotations in the hand of Cardinal Sirleto that were used for the reforms that produced the Tridentine missal under Pope Pius V after the Council of Trent in 1570.12 The calendar and services of the Roman rite and the design and types of Italian printers as established in the tens of thousands of missals issued in the fifteenth century had a lasting impact.

Decisions on how and where to include music in printed books would have been made by an editor or editorial committee13 and set down in a manuscript exemplar to serve as a copy text for the printer, but unfortunately no such copy text has been identified and the printed books must speak for the publication process. What is apparently the first printed missal, attributed to Central Italy about 1472, leaves so much space for insertions by hand of rubrics, music, and illuminations that both copies have at times been treated as manuscripts.14 A copy was found in 1964 in the manuscript collections of the Biblioteca Vaticana (Urb. lat. 109, called BV below) in the intact library of Federico da Montefeltro, the Duke of Urbino, for whom it was illuminated.15 I recently identified another copy from a Central Italian Benedictine monastery, now in the Newberry Library (Inc. f7428.5, called NL below), also called a manuscript in the inventory made at the time of its purchase in 1890. The size of the book is Median folio (NL, 328 × 220mm heavily trimmed; BV, 348 × 243mm, slightly trimmed). Both copies are vellum rather than paper, since skin was traditionally preferred for manuscript liturgical books because of their heavy use and presumed longevity. Pages are laid out in two columns of twenty-nine lines of text or space for seven texted music staves. The edition first appeared (NL) with about one-third of the total space blank for text in red, music and initials to be added by hand. At some point it was decided to run the sheets through the press again to print in red rubrics of three or more lines (BV), still relying on a rubricator for isolated abbreviations for verses and responses. Space for Roman plainchant, for which type was still four years in the future, was left immediately following rubrics for performance on forty-seven of 692 pages, primarily for prefaces but also for such individual chants as the “Ecce lignum” of Good Friday and “Pater noster” of the Canon. That space was filled in by hand in both copies with plainchant in square Roman notation on two-, three-, and four-line red staves (see Fig. 1).

The relationship of music to alphabetic text in liturgical books had been carefully worked out in manuscripts and delineated in the ruling of pages that preceded scribal entry.16 Whereas in the rest of the first missal the printer has allotted the space of three lines of text to each staff and to text underlay, this first appearance of music in the book is one line short and the solution was to leave both text and chant to be entered in manuscript. Presumably the sequence of scribal activity was black text, red lines for staves, black neumes, and red initials. Without the rules that were the usual guide for scribes, the space was approached quite differently in each copy. BV’s music scribe chose to enter a two-line staff over the first line of text, allowing room for the first low note but placing the clef at the ...