eBook - ePub

The Intonation of English Statements and Questions

A Compositional Interpretation

This is a test

- 316 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

English sentence prosody provides cues to both focus structure and speaker attitude. Taking the phonological model of intonation developed by Pierrehumbert (1880 et seq.) as point of departure, this work illuminates the communicative function of English pitch contours by (1) giving a detailed survey of phrase-final contours found in statements and questions, and (2) investigating what attitudinal features determine choice of phrasal tones in these utterance types. This comprehensive study will be of interest to linguists in a number of fields, ranging from prosody to semantics, pragmatics, and discourse analysis.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Intonation of English Statements and Questions by Christine Bartels in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Intonation of English Statements and Questions

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

1.1 INTONATIONAL MEANING: DELINEATING THE TASK

Just as a line can be described either in terms of its slope or of its end-points, a pitch contour can be described either as a sequence of pitch movements—rises and falls—or as the interpolations between a series of two or more level target tones. The question which of these descriptive approaches is more likely to capture the nature of the phonological building blocks of English phrasal contours is probably as old as research into English intonation itself; it is popularly known as the controversy of ‘levels’ vs. ‘configurations’ (Bolinger 1951; for discussion see, e.g., Ladd 1980).

But regardless of the particular phonological constituent structure assumed for an English intonation contour, following Halliday (1967) we can distinguish between two general structural aspects of the pitch pattern that are interpretationally relevant (not counting issues of phrasing and variations in pitch range). The first is the distribution of pitch accents—pitch maxima or minima aligned with stressed syllables. The second is the choice of type of accent tones as well as phrasal (non-accent) tones out of a limited inventory. For instance, in ‘level’ models, tone types differ typically in height specification relative to the speaker’s pitch range; in ‘movement’ models, they differ among other things in directionality of movement.

The investigation to be presented here is based on two basic assumptions. One is that the two structural aspects of English contours mentioned above have different functions in discourse and thus are subject to different constraints on the interface between phonology and semantics/pragmatics. Pitch accent placement, to the extent that it is determined by such interface constraints, is governed by intraclausal focus structure. By contrast, choice of tones, to the extent that it is determined by interface constraints, is governed by interclausal dependencies and interactive attitudinal aspects, that is, aspects of illocutionary force in the most general sense.1

While considerable light has been shed on the first of these sets of constraints—the relation between focus structure and accent placement (see Selkirk 1995 for review)—no detailed, systematic investigation of the second—interactively relevant, grammaticized contour features represented by tone choice—has yet been carried out. This is where the present work hopes to make a contribution.

The second general assumption, which comes into play specifically in the investigation of tone choice, is that, like strings on other tiers of linguistic structure, the tone sequences of English intonation contours can be compositionally interpreted: the overall meaning of a tune is built up from the meanings of its smallest meaning-bearing constituents, that is, tonal morphemes. That is not to say that every tone must be inherently meaning bearing. For example, as will be seen, I do allow for the possibility of epenthetical tones that owe their appearance to purely phonological constraints on prosodic structure. Also, the assumption is not intended to rule out the possibility of certain contours being holistic in their interpretation, in the same way as lexical expressions like kick the bucket. The principle of compositionality is taken as a working hypothesis here guiding the development of testable claims, no more and no less.

Given these basic assumptions, the central questions surrounding tone choice in English might be expressed as follows. (1) What tonal constituents represent which interpretational (discourse functional) features? (2) How do the features cued by co-occurring tones in an utterance combine to produce the observed overall effect on interpretation (discourse function)? (3) Can we make a plausible case for associating a given tone at some level of abstraction with the same interpretational feature across all occurrences, independent of lexical content and situational context, despite the fact that tunes in different contexts appear to yield highly variable effects? (4) Relatedly, does tonal meaning interact in principled ways with nontonal aspects of utterance meaning?

Any research program that addresses these questions is by nature interdisciplinary, since it must involve two simultaneous categorization tasks, one phonological and one semantico-pragmatic: on the one hand, the identification of those tonal building blocks selected or derived from the inventory of phonological primitives which make a distinctive contribution to utterance meaning/function—the tonal morphemes—and on the other, the identification and formal characterization of the relevant, tonally cued interpretational features.

To be sure, a certain number of proposals for the mapping of into-national into discourse-level interpretational features have already been put forward in the past (e.g., Liberman and Sag 1974, Sag and Liberman 1975, Cruttenden 1981, Bolinger 1982, Gussenhoven 1984, Merin 1983, Carlson 1984, Lindsey 1985, Pierrehumbert and Hirschberg 1990). However, most of them build on phonological models that have since been replaced by more detailed, formally explicit successors (one notable exception being Pierrehumbert and Hirschberg (1990), which is based on the model of Pierrehumbert (1980) and Beckman and Pierrehumbert (1986)), or on semantico-pragmatic concepts that capture valid intuitions but do not suffice from today’s point of view for a comprehensive, formal functional analysis. Consequently their insights need to be re-evaluated with respect to the current status of phonological and semantic/pragmatic theory. In turn, a convincing account of tonal meaning is likely to contribute to further development both of the phonological model and of our understanding of discourse structure.

1.2 CHOICE OF EMPIRICAL DOMAIN

The present study is both more limited and more extensive than the earlier works mentioned above. It is more limited in that it addresses the question of tonal meaning for only a subset of English tones, in only a subset of the clausal positions in which they may occur: the discussion is confined, by and large, to the phrasal tones that can be observed between the last pitch accent of an utterance and its end. (These tones will be more specifically characterized in Ch. 2, where I introduce the phonological framework assumed here.) Furthermore, the empirical scope of the investigation is restricted to a relatively narrow range of utterance types: simple, syntactically “complete,” monoclausal declarative or interrogative sentences. This means, for example, that I am leaving the systematic analysis of tag questions to future effort, widespread as this utterance type is in English.

On the other hand, the present study goes beyond earlier works in that, within the confines of its empirical domain, I am examining the intonational possibilities, and the interaction of tonal with lexical and contextual factors, at a level of detail these did not aim for. My expectation is that the results obtained in this fashion for the chosen utterance types will essentially carry over to extensions of the empirical domain—for instance, to the interpretation of nonfinal phrasal tones in syntactically complex sentences.

As a glance at the table of contents of this dissertation reveals already, most of the discussion will be concerned with evidence from questions. Why focus on questions in a first foray? For one thing, because as traditionally defined sentence types go, questions are exceptionally flexible from an intonational perspective; any phonologically licensed combination of tones may occur, as is amply illustrated in Bolinger’s (1957) classic survey entitled Interrogative Structures in American English, which I will frequently draw on. As Fries (1964) put it, “there seem to be no intonation sequences on questions as a whole that are not also found on other types of utterances, and no intonation sequences on other types of utterances that are not found on questions.” In short, a well-rounded survey of questions is one way to savor the whole cake without having to digest all of it.

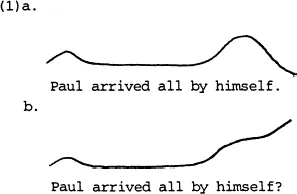

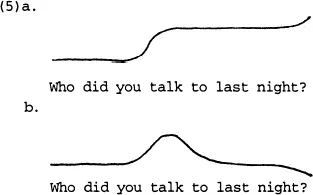

This assessment seems to contrast with the common conception that intonation correlates with sentence type. In discussions that are only peripherally concerned with intonation one often encounters reference to “question intonation”—meaning that the speaker’s pitch level is rising, or at least does not decline, at the end of the utterance. (Conversely, “statement intonation” is perceived to be characterized by a final fall.) An empirical fact supporting this widespread intuition is that if there are no strong contextual cues blocking the effect, a final rise can be sufficient to change the speech act type of a declarative sentence from the “unmarked,” syntactically cued one—‘statement’, or ‘assertion’—to a marked one—‘question’; compare (la) with (lb).2

Conversely, a syntactically interrogative sentence that does not show rising intonation is more likely to be perceived as a statement in suitable context.

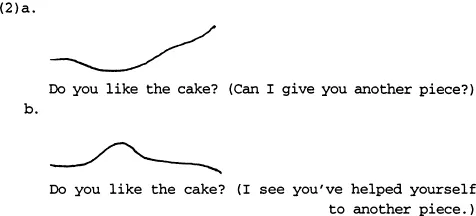

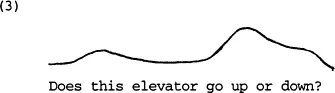

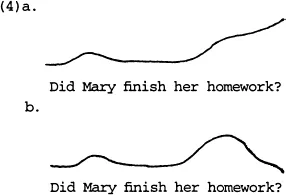

As I will argue in the course of my presentation, there is indeed a principled basis to the intuition that, other things being equal, lack of final pitch fall reflects a quality of ‘questionhood’. However, statistically speaking, the final rise is probably not the most frequent tonal pattern found in questions. Alternative questions like (3) require a final fall, for one. Yes-no questions like (4) and wh-questions like (5) may either rise or fall, but corpus studies have shown that, at least in yes-no questions, falling variants appear to be more common than rising ones (cf. Chs. 5 and 6.)

These few examples should make it clear from the outset, then, that there is no direct correlation in questions between syntactic subtype and intonation, and further, that in empirical descriptions, there is little use for the simplistic notion of a uniform “question intonation.”

Aside from the intonational variety found in questions, a second, more subjective motivation for my choice of empirical domain was that in my view, past work on tonal meaning (with the notable exception of Merin 1983) has had a tendency to base its claims on evidence from statements, foregrounding epistemic aspects that appear to account reasonably well for tonal distribution in monologues but fail to predict the complexities of tone-dependent connotations in dialogues. An investigation of questions, by contrast, naturally brings out situation-specific attitudinal factors, which I hypothesized from the start to provide more universally valid interpretational correlates of tone choice. If one assumes that dialogue is the more fundamental type of communicative “game,” and monologue a derived variant, it stands to reason that we are more likely to get at the fundamental ‘meanings’ of phrasal tones by looking at their effects in dialogue.

Of course, a well-founded theory of question intonation cannot exist in a vacuum, especially not if one subscribes to the primacy of dialogue; it must necessarily be accompanied by a theory of statement intonation. As is often the case, contrasting the declared category of interest with a minimally different one turns out to be the only way here to chisel away at indirect or coincidental correlations and identify genuinely constitutive properties. And in fact, both expository and substantive considerations that will soon become apparent argue for tackling a dialogue-oriented analysis of statement intonation first, before going on to the investigation of questions.

But before I do so, it is now high time to settle an important preliminary issue. How exactly are questions, and by contrast statements, to be defined?

1.3 DEFINING ‘STATEMENT’ AND ‘QUESTION’

Common usage of the term ‘question’ encompasses two overlapping sets of utterances: first, those which are syntactically defined as interrogatives—that is, ‘wh-questions’ and sentences showing subject-AUX inversion (yes-no questions and alternative questions)—whether or not they function as questions in the discourse; and second, those utterances which do in fact have the pragmatic force of questions, regardless of whether or not their syntactic structure identifies them as interrogatives. Of course, the set of syntactically interrogative utterances and that of questions, functionally characterized, show considerable overlap: the unmarked, most frequent use of interrogatives is indeed as questions, however the latter are specifically defined. Mutatis mutandis, the same inclusive usage is widely encountered with ‘statements’/‘assertions’.

I will follow a different, more restrictive terminological usage here. I will treat ‘question’ as a purely functional notion distinct from the structural ‘interrogative’; and I draw the same distinction between the functional notion ‘statement’/‘assertion’ and the structural ‘declarative’.3

The crucial point is, of course, which functional criterion is invoked to define questions and statements. This is a controversial issue. One view is expressed by Dwight Bolinger, the author of the enzyclopedic survey of question characteristics in American English mentioned above (Bolinger 1957). Bolinger denies the possibility of a single criterion for questionhood and explicitly confines the task of delimiting his domain to identifying those utterance classes “which the average speaker would unreflectingly label Q[uestions]” (p.3).

I am taking a different tack here, at the risk of doing violence to one or the other “average speaker’s” intuitions on borderline cases. Following, for example, Lyons (1977) and Jacobs (1991), I define questions as utterances that convey perceived relative lack of information—simply put, speaker uncertainty—regarding a relevant aspect of propositional content. In formal terms taken from Jacobs, I assume that what characterizes a question—what one might call its distinctive ‘felicity condition’ in the terminology of speech act theory—is that in the discourse situation at speech time, the speaker’s information status is not such that he is able to specify sufficiently the extension of a sentence constituent (in the case of wh-questions) or the set of validity predicates applicable to the sentence proposition (in the case of yes-no questions). Conversely, what characterizes statements is lack of speaker uncertainty, thus defined.4

This is a comparatively minimal definition. It contrasts with a substantial tradition of semantic and speech act-theoretic definitions of questions that make crucial reference to the answers a question is said to seek to elicit. At the sentence semantic level, questions have been said by some analysts to have as their denotation the set of propositions each of which is a possible answer (Hamblin 1973), or a true answer (Karttunen 1978). Others have made explicit attempts to accommodate the illocutionary force of prototypical questions within linguistic structure by analyzing them as a subtype of requests (...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1. INTRODUCTION

- 2. INTONATIONAL STRUCTURE IN ENGLISH

- 3. STATEMENTS

- 4. ALTERNATIVE QUESTIONS

- 5. YES-NO QUESTIONS

- 6. WH-QUESTIONS

- 7. NON-INTERROGATIVE QUESTIONS

- 8. NON-QUESTION INTERROGATES

- 9. CONCLUSION

- Bibliography

- Index