![]()

Chapter 1

Thracians, Illyrians and Celts

At the time when the Greeks were already familiar to some extent with the geography and ethnography of central Europe the upper Danube was firmly in the hands of the Celts, whereas the lower reaches, from the Iron Gates to the Black Sea, had from time immemorial belonged to the settlement area of the Thracians and the Getae. While, of course, some details concerning the races who inhabited the valleys of the western and southern tributaries of the Danube between Vienna and the Iron Gates were available to the Greeks, they were scarcely adequate as a basis for an authoritative ethnic appraisal. The earliest information is to be found in the Iliad: ‘Zeus … turned his shining eyes away into the distance, where he saw the lands of the horse-rearing Thracians and the Mysoi who fight hand to hand… .’1 Hellenic philologists queried this passage in Homer, as the Greeks in that era knew only of the existence of the Mysoi in Mysia, part of Asia Minor. It was Posidonius, the last great scholar of Hellenism, who provided the right answer by pointing out that a tribe called the Mysoi lived north of the Thracians and could be identified as the Mysoi mentioned by Homer.2

This old controversy is to some extent characteristic of the whole of the Greeks’ knowledge of their northern neighbours. In archaic times they had a pretty clear picture of the Danube river-system and of the inhabitants of the Adriatic coast. This information, gathered by Greek traders, was in part forgotten in the classical period, along with the decline of Greek trade with the north, and in part became intermingled with mythology and hence gradually distorted.3 It became, for example, a self-evident truth that one arm of the Danube flowed into the Adriatic and hence that the Balkans were an island.4 It was not until Roman expansion to the north that a fresh breeze bearing new knowledge put an end to what was in the main idle speculation and information derived from books. Even as far as the Mysoi-Moisoi were concerned, Posi-donius’ information was only scanty, whereas a Roman army under the command of C. Scribonius Curio, advancing from Macedonia as far as the Danube between 76 and 72 B.C., brought back more up-to-date details of the inhabitants of the Danube valley.5 Greek scholars were interested in the history and ethnography of central Europe only in so far as the barbarians were involved in events in the Greek homeland. This episodic information which has been handed down is, however, adequate for a sketch to be made of the main features of political development on the middle Danube in the last centuries B.C.

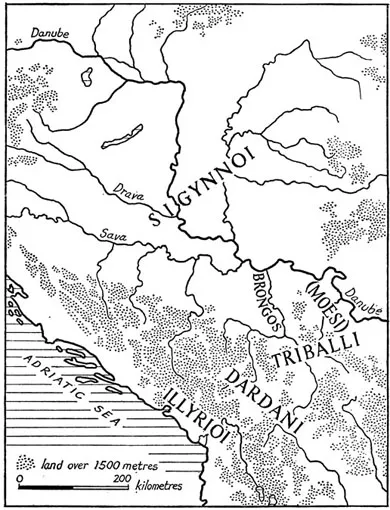

Apart from the Mysoi referred to by Homer, the earliest peoples on the middle Danube mentioned by name are those listed by Herodotus and Hecataeus, e.g. the Sindoi, Sigynnoi, Kaulikoi, etc., none of whom played any part in the subsequent history of this area.6 Later they were not included among the peoples who lived in the Danube valley.7 They were, however, tribes who were still in contact with Greek trade, whereas later tribes for the most part only came within the Greek and Roman range of vision if they had become the enemies or allies of Macedonia or Rome. It has recently been assumed that the Sigynnoi, who probably lived in the great Hungarian plain, traded with the Veneti in Istria, who in turn were involved in early Greek trade on the Adriatic coast.8 Traces of these trading contacts are attested by a few late archaic finds in Hungary and the northern Balkans.9 In the fifth century B.C. the ethnographic picture at least of present-day Serbia becomes somewhat clearer (Fig. 1). According to Herodotus the valley of the Morava (which he calls the Brongos) below Niš belonged to the Triballi, a tribe centred north of the Balkan mountains on the Danube around Oescus (Bulgarian: Gigen), and these people later often proved troublesome to the Macedonians. The western neighbours of the Triballi were the lllyrians, for the Angros, a tributary of the Brongos which cannot be identified with certainty (Ibar ? Zapadna Morava ? Toplica ?), rises in Illyrian country and flows into the Brongos in the area of the Triballi. So much for Herodotus.10 Later sources11 report the advance of the Illyrian Autariatae into the territory of the Triballi about the end of the fifth century B.C. and not much later there are reports of Celtic conquests in the Carpathian region and on the lower Danube. After the Autariatae had driven the Triballi out of the Morava valley they themselves were subdued at the beginning of the fourth century by the Celts,12 who were emerging as a new influence in the Carpathian region and in the Balkans. The known ethnic pattern of the original inhabitants in the Roman period first began to take shape as the result of the Celticization of many areas in south-east Europe, and it is only after the arrival of the Celts that it is possible to follow the political changes on the middle Danube more precisely.

Figure 1 The area of the middle Danube in the fifth century B.C.

The Triballi belonged to the Thraco-Getic ethnic group which inhabited the eastern half of the Balkan peninsula. The Autariatae were an Illyrian tribe which had settled in the western half. The third ethnic and linguistic component, the Celts, probably came in part from northern Italy and in part along the Danube from the west.13 The Thracians, lllyrians and Celts were the three most important ethnic and linguistic groups in south-east Europe, and in Roman times they made up the native inhabitants of Pannonia and Moesia Superior. The linguistic boundaries ran through these two provinces: the Celtic-Illyrian through Pannonia and the Illyrian-Thracian through Moesia Superior.14 This is one reason why sizeable political units were only rarely established. Neither Pannonia nor Moesia Superior were known as geographic or political concepts in pre-Roman times; both regions belonged for the most part to political structures which had their centres outside the country.

As far as the Thracians and lllyrians are concerned, the problems surrounding their origin and linguistic classification are today much in a state of flux. There was a tendency in the last decade to reject the theory of linguistic uniformity among the Thracians as well as among the lllyrians, and to reserve the terms ‘Thracian’ and ‘Illyrian’ for a smaller and more readily definable tribal group. After the abandonment of suspect Pan-Illyrism in the 1930s, philologists came to recognize that the Veneti and Liburni on the northern Adriatic coast spoke a language related to, though different from, Illyrian.15 Analysis of the earliest information about the lllyrians on the Adriatic indicates that the name Illyrioi applies only to a small area in the south of what was later to become the province of Dalmatia;16 a critical classification of Illyrian names17 has established that there were two or three distinct areas in the provinces of Pannonia and Dalmatia. Finally, doubts were also raised by archaeologists who attributed the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age culture of northern Dalmatia to a people who differed from the lllyrians.18 The Dalmatians and Pannonians, therefore, were either not lllyrians or at best were only related linguistically; but they did not speak the same language as their neighbours to the south, who alone are regarded in the sources as lllyrians. In the case of the Thracians the situation is even more confused. Classical scholars were convinced that the Getae and Dacians spoke the same language19 and that the Thracians and Getae were in fact one and the same people.20 The mapping of the place-names in Dacia, Moesia and Thrace recently produced the hypothesis that the Thracians in the wider sense belonged to two different linguistic groups: partly to the Thraco- Getic and partly to the Dacian-Moesian.21 This division is based principally on the suffixes (-dava, -para, -sara, etc.), the geographical distribution of which is to some extent restricted. Historically there would probably have been better justification for a division into a Dacian-Getic group and a Thraco-Mysic group; argument based on and restricted to place-names is too narrow a basis for such sweeping hypotheses. In any case Pannonia and Moesia Superior were on the periphery of both the lllyrians and the Thracians in the wider sense of those terms. For the moment it will perhaps not be misleading if, following tradition, these fringe races are regarded as lllyrians and Thracians, though we must not overlook the fact that dialects—probably more so then than now— affected linguistic uniformity. A number of tribes are known to have existed along the linguistic boundaries, right inside Pannonia and Moesia Superior, though the linguistic and ethnic groups to which they belonged have not been conclusively established. Of the tribes whose history will be described later, the Dardani are variously taken to be of Illyrian and of Thracian stock;22 the Scordisci were, of course, a group established by the Celts; in imperial times, however, their names were Illyrian (Pannonian),23 and some sources include them among the Thracians;24 it is only recently that the Eravisci have been conclusively identified as a Celtic race.25 The contact zone between lllyrians, Thracians and Celts was obviously a very broad one, and their relations with one another were subject to constant fluctuation, which ceased only with the Roman conquest.

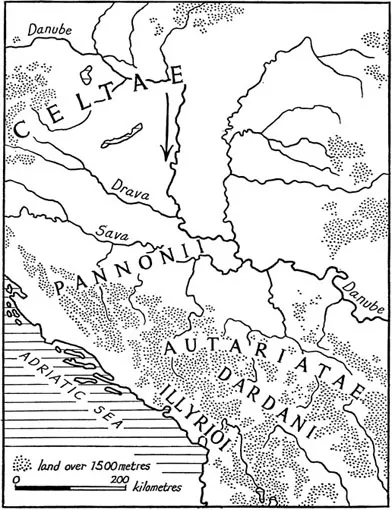

Celtic expansion reached the Carpathian area roughly at the same time as the Celtic invasion of Italy, that is at the beginning of the fourth century B.C. According to Celtic legend, 300,000 people migrated to Italy and Illyria: Livy’s account mentions Bellovesus and Sigovesus, nephews of the Celtic king Ambi-gatus, who sent them against Italy and against the inhabitants of the Hercynia silva respectively.26 The Celtic legend in Pompeius Trogus describes wars against the native inhabitants which lasted for years and led to the gradual subjugation of the Pannonians.27 Early La Tène finds in Pannonia suggest that the Celts advanced along the Danube and conquered only the north-west part of the Carpathian region in the fourth century B.C.28 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 The area of the middle Danube in the fourth century B.C.

Another arm of Celtic migration to the east probably started from northern Italy, for, while fighting on the Danube, Alexander the Great received an embassy from the ‘Adriatic Celts’.29 This incident coincided with the violent collapse of the Autariatae who, according to some sources, were forced to yield to the Celtic advance, and after a long and turbulent wandering here and there were finally wiped out.30 Towards the end of the fourth century the Celts, who had already established themselves in Pannonia, renewed their raids on the Balkan peninsula; these soon brought them into conflict with the king of Macedonia on the northern border of Thrace.31 These raids were the prelude to the great Celtic invasion of the Balkans in 279 B.C., which, in many respects, resembled the migration of more than a century earlier. On this occasion, too, the numbers involved seem to have been very large; Justin in his epitome of Pompeius Trogus mentions a charge by 150,000 infantrymen under Brennus’ command,32 and even if this figure is grossly exaggerated, since Diodorus mentions only 50,000,33 this much is certain: the enterprise was concerned from the outset with finding new areas in which to settle. Again Celtic legend indicates that there were two leaders, Belgius (or Bolgius) and Brennus, whereas a variant states that there was a third group under the command of Cerethrius.34 A section of the people and of the troops stayed behind to protect the homeland (oikeia),35 which can probably be identified as the area in Pannonia already consolidated by the Celts. From the dating of a Greek bronze vessel found in a grave in the La Tène cemetery at Szob on the Danube bend in Hungary (pl. 1a) the only...