![]()

1 Bridge employment

An introduction and overview of the handbook

Carlos-María Alcover, Gabriela Topa, Emma Parry, Franco Fraccaroli and Marco Depolo

The changing nature of retirement in the twenty-first century

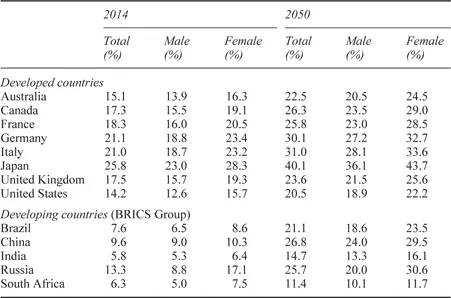

Progressively increasing life expectancy and attendant aging of the population is a worldwide phenomenon, particularly in Western economically advanced countries. Forecasts for the coming decades suggest that the trend is likely to intensify, reaching hitherto unimagined proportions. The proportion of the world’s people aged 60 or more in 2011 will double in percentage terms by 2050, when this age group will account for some two billion people and 22 percent of the population (United Nations 2011). These changes in population structure are a consequence of declining fertility and mortality rates (known as the demographic transition) and shifting migration trends. Fertility decline reduces family size and produces smaller cohorts at younger ages, while mortality decline raises life expectancy. The combined outcome is population aging (Alley and Crimmins 2007). Table 1.1 shows the percentage of the population aged 65 and over in selected developed and developing countries in 2014 and 2050.

As may be observed in Table 1.1, countries like Japan, Germany and Italy will reach percentages close to 25 percent by 2014, although the percentages are significantly lower among the BRICS group, with the exception of Russia. Meanwhile, the forecast for 2050 points to a major increase in the number of people aged 65 and over in the developed countries, and even faster growth in the BRICS resulting in a tripling of the percentages in Brazil, China and India.

These marked population trends will eventually require a reassessment of the balance between the period of people’s working lives and the length of their retirement (Engelhardt 2012), taking into account also the better health condition of people over 55 in relation to the past, in order to maintain pension systems and welfare programs for the elderly (Börsch-Supan et al. 2009; de Preter et al. 2013). As leading experts have warned for years now, for most developed countries, the traditional pay-as-you-go social security system includes promises that cannot be kept without significant system reforms; and in the absence of true reforms, current systems are fiscally unsustainable (see, e.g., Gruber and Wise 2005). Retirement is a matter of global significance which influences and determines the sustainable financial and social development of countries and societies as a whole (Wang 2013). Consequently, these international trends require a reformulation and further research on aging and work, and mid and late career structures (Peiró et al. 2013; Shultz and Adams 2007; van der Heijden et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2012).

Table 1.1 Estimated percentage of population aged 65 and over in developed and developing (BRICS group) countries in 2014 and 2050

Source: US Census Bureau, International Data Base, June 2010 version.

Research carried out mainly in the United States, Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom and the countries of northern Europe has shown that the trend toward the early retirement options, promoted by governments in order to avoid high unemployment rates mainly among young people, characteristic of the latter two decades of the twentieth century has halted and even gone into reverse (Cahill et al. 2006a; Kantarci and van Soest 2008; Lee et al. 2011; Peiró et al. 2013; Phillipson and Smith 2005; Quinn 2010; Saba and Guerin 2005). The context for retirement in developed and developing countries is rapidly changing with a shift from ‘pro-retirement’ to ‘pro-work’ (Wang and Shultz 2012). Meanwhile, Japan traditionally has followed a different pattern (Raymo et al. 2009), as retirement in Japan is a particularly lengthy, gradual process, especially for male workers (Shimizutani 2011), and the participation of older people in the workforce has usually been high among men and women, both in the 60–64 age bracket and among those aged over 65 years, which are the higher rates among OECD countries.

The trend to prolong working life has even been detected in countries where early retirement has been used as an organizational strategy to handle challenges in the labor market (Schalk et al. 2010), making it an involuntary option forced upon retirees by organizational policies so that they are bereft of any influence over the decision. Such a situation may lead to adverse psychological outcomes, lower levels of household income and lower well-being and life satisfaction (Alcover et al. 2012; Bender 2012; Dorn and Sousa-Poza 2007; Hershey and Henkens in press; Noone et al. 2013). Recent studies show that in the United States the majority of older workers are employed, or plan to work, part-time and in temporary jobs (Giandrea et al. 2009; Raymo et al. 2010), while the data from European countries suggest that paid work between the ages of 60 and 70 is the domain of persons with high socio-economic status (Komp et al. 2010). Though older workers’ motives for wishing to stay in the labor market may differ, the results of a recent meta-analysis suggest that they do so basically to satisfy intrinsic interests, such as the nature of the work, the satisfaction it provides and the motivation of success, for social reasons and to gain financial security (Kooij et al. 2011). All of this is redefining the conventional concepts of career and retirement.

Comparisons of extensive international surveys (Topa et al. in press) such as SHARE (Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe; Börsch-Supan and Jürges 2005), HRS (Health and Retirement Study) from the United States and ELSA (English Longitudinal Study of Ageing) from the United Kingdom, have shown that the rate of employment among older workers (i.e., those aged over 50) is much higher in the United States than in Europe, but the difference is even more pronounced among workers aged 60–64 and over. For instance, data from the first eight waves of HRS reveal that 47 percent of retirees experienced post-retirement employment, with 43 percent of retired women making the transition compared to 50 percent of retired men (Pleau 2010). However, longitudinal data for the last 33 years display a modest curvilinear trend in post-retirement employment in the United States (Pleau and Shauman 2013). Despite the existence of considerable differences between countries, labor markets in Europe are characterized by low employment and labor-force participation rates among older workers due to early retirement from work (Engelhardt 2012; von Nordheim 2004). Nevertheless, there is a general trend to prolong working life through a variety of flexible working practices in the majority of the developed nations, as the contents of this book will show.

Over the past two decades the conceptualization of work and retirement as opposite states among older workers has become obsolete in most developed countries (Cahill etal. 2013), and models conceived within the work/non-work dichotomy can no longer accommodate the new, creative forms of living that many men and especially women now aspire to (Everingham et al. 2007). One of the main consequences of this trend to prolong working life using alternative working practices has been the replacement of the concept of trajectory by that of transition to define the work-life cycle (Elder and Johnson 2003). Thus, a consensus has arisen among researchers that retirement is not a single event but rather a process that older individuals go through over a variable period of years (Marshall et al. 2001; Shultz and Wang 2011; Szinovacz 2003), with dozens of possible combinations of paid work and time out from the labor force (Pleau and Shauman 2013). Retirement, then, represents a longitudinal developmental process through which workers tend to reduce their psychological attachment to work and behaviorally withdraw from the workforce (Wang 2013; Wang et al. 2011). Above the age of 50 both men and women face a series of work-related, family, personal, financial and leisure events that condition their decisions to stay in the labor market and to seek alternatives to the conventional full-time job in order to prolong their activity beyond the normal retirement age.

This development has substantially altered the linearity of a long period in people’s lives that is given over to work followed by definitive retirement and the passage to complete and irreversible labor-force withdrawal. Retirement from work has changed from a landmark event to a gradual process (Cahill et al. 2006b; Calvo et al. 2009; Vickerstaff 2007), or from total into partial retirement (Beehr and Bennett 2007). As underlined by Wang and Schultz (2012: 13), for many old workers ‘retirement is no longer synonymous with the end of one’s career’.

Diverse modalities of transitional or gradual retirement, including ‘phased retirement’, ‘partial retirement’, ‘bridge employment’ and ‘re-entry’, are increasingly prevalent in older workers’ lives today (Cahill et al. 2013).

‘Phased retirement’ refers to the alternative of working shorter hours for the same employer. ‘Partial retirement’ refers to a job change from a career job to a new full-time or part-time position (Kantarci and van Soest 2008). ‘Bridge jobs’ involve a change in employer and sometimes a switch from wage-and-salary work to self-employment (Cahill et al. 2013). Finally, ‘re-entry’ into the labor force after retiring can come about in one of two ways (Cahill et al. 2011). It can be either (1) planned as a way to move out of career employment gradually by taking a break from full-time work before moving to another job, which may or may not be parttime; or (2) unplanned, acting as a fallback where an individual’s standard of living in retirement fails to meet expectations, or as a way to reinforce or ensure retirement income in anticipation of future contingencies. In short, ‘re-entry’ has now become relatively common, and as Shultz and Wang (2011: 171) recently noted, ‘there are individuals now who retire multiple times throughout their lives’.

Though different forms of bridge employment and gradual retirement began to emerge in the 1990s (Doeringer 1990; Ruhm 1990, 1994), these transitions have become ever more complex in the twenty-first century as a consequence of the increasing ‘negotiation’ and ‘deinstitutionalization’ of these options, with the result that workers and organizations now commonly agree the terms defining employment relations on a flexible, individual basis (Peterson and Murphy 2010; Phillipson 2002; Vickerstaff 2007). In short, the lives of people above the age of 50 have become less predictable (Henretta 2003), and variable, complex and contingent transition experiences lasting in some cases into an individual’s seventies have come to define what was traditionally a clearly delineated stage in the life course of almost everyone.

To sum up, the available alternatives for the postponement of retirement labor-force re-entry tend to blur the work/non-work boundary and what it means to retire.

Conceptualization of bridge employment

The most common definition of bridge employment refers to jobs that follow career or full-time employment and precede complete labor-force withdrawal or retirement from work (Cahill et al. 2013; Feldman and Kim 2000; Shultz 2003a). Bridge employment alternatives may therefore be considered forms of retirement that prolong working life, allowing the term full retirement to be used to refer to final withdrawal from the workforce (Gobeski and Beehr 2009). The transitions characterizing bridge employment occur both within the individual’s own profession and in other occupations, and they can take the form of (full-or parttime) salaried work, permanent or temporary jobs and self-employment (Beehr and Bennett 2007).

In short, bridge employment can be conceptualized in two primary ways (Gobeski and Beehr 2009; Wang et al. 2008), namely career-consistent bridge employment and non-career bridge employment. Bridge employment in the career field may occur either within the same organization as the career job or in a different organization where the older person works in the same occupation (Raymo etal. 2004). However, it is non-career bridge employment (i.e., bridge employment in a different field) that is most common among older workers, who usually accept lower pay and status in return for the flexibility of a bridge job (Feldman 1994; Shultz 2003b).

Bridge employment involving some form of self-employment appears to be the most common alternative as people grow older, because it allows greater freedom to satisfy needs like flexible working hours and personal autonomy, whereas salaried jobs tend to be more restrictive. This shows that entrepreneurial attitudes and behavior are in no way incompatible with old age (Davis 2003). The option of self-employment as a form of bridge working has positive consequences not only for older workers, but also for political leaders and employers, as it allows older workers to continue earning and paying social security dues and taxes, while providing organizations with the benefit of their knowledge, skills and experience via contingent agreements (Giandrea et al. 2008; Kim and DeVaney 2005; Zissimopoulos and Karoly 2009). In fact, the motivation and capacity to engage in a bridge job can be considered a measure of work ability, as Ilmarinen (2009a) defines this construct. Work ability describes the relation and balance between individual resources (health, competence, work v...