eBook - ePub

Nature's Place (Routledge Revivals)

Conservation Sites and Countryside Change

This is a test

- 210 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Nature conservation has become increasingly important in Britain over the last three decades. This title, first published in 1986, deals with the critical issues surrounding nature conservation and wildlife protection. The book is broad in scope, with a focus on the 1981 Wildlife and Countryside Act and its provisions for the protection of wildlife habitats in Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs). This follows an historical account of habitat loss over the past 200 years and the origins of conservation and site-protection policy. This reissue will be of particular value to professionals, voluntary workers and students with an interest in the origins, developments and practice of nature conservation.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Nature's Place (Routledge Revivals) by William M. Adams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Conservation & Protection. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The changing countryside

The ratchet of change

In January 1981, debate over the Wildlife and Countryside Bill was at its height in Parliament. The Bill was supposed to be the most thorough treatment of conservation and the countryside for many years, and among other things it was hoped that it would guarantee the survival of the last vestigial patches of semi-natural habitat in Britain. Controversy over the proposals was already fierce. How serious a problem was habitat loss? How destructive was modern intensive agriculture? How should farmers, and others, be prevented from damaging wildlife sites? In the middle of all this, an article appeared in New Scientist written by David Goode, who was the deputy chief scientist of the Nature Conservancy Council, the government body responsible for nature conservation. Called ‘the threat to wildlife habitats’, the article explained quite simply that the Bill as it stood was not going to be strong enough to stop habitat loss.

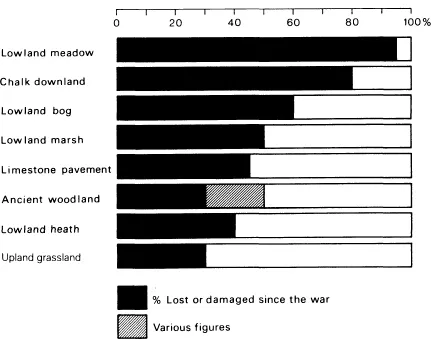

Coming from such a source and at such a time, this article opened up the debate on habitat loss, and incidentally is rumoured to have won the NCC a sharp rap across the knuckles from the government for being too free with its opinions. The course of the debate, and the effect of the legislation eventually passed, are described later in this book. The figures presented by David Goode in his article showed that the most important areas for wildlife in Britain, scheduled as SSSIS, were being destroyed or degraded at a rate of 100 per year, more in some areas. In all habitats, chalk grassland, heathland, ancient woodland or wetlands, the story of shrinkage and fragmentation was the same. These figures themselves were confirmed in 1984 when the NCC published Nature conservation in Great Britain, which summarised information on the destruction of natural and semi-natural habitats in Britain since the war. By 1984, 95% of lowland grasslands and herb-rich hay meadows lacked any significant wildlife interest, and only 3% were unaffected by agricultural improvement (Fig. 1.1). Eighty per cent of lowland chalk and limestone grasslands had been significantly damaged by agricultural ‘reclamation’ or the ending of former grazing regimes. Forty per cent of lowland heathland had been destroyed, most by agricultural conversion, afforestation or building: the heaths of Breckland shrank from 9200 ha in 1950 to 4500 ha in 1980, and the Dorset heathland had been reduced from 10000 ha to 5600 ha since 1960, while the remaining pieces were fragmented and small in extent, vulnerable to damage by fire.

Figure 1.1 Estimates of the loss of wildlife habitats in postwar Britain.

Of limestone pavements in the North of England, 45% had been damaged or destroyed by 1984, largely by the gardening trade for rockery stone. Between 30 and 50% of ancient broadleaved woodland, (continuous on one site since AD 1600), in England and Wales had been lost since the war, mostly due to replanting with conifer species. Fenland drainage had reduced the area of fens in East Anglia from 10 000 to 1000 ha between 1930 and 1981. Sixty per cent of lowland raised mires had been damaged or destroyed by peat digging or afforestation since World War II, and 30% of upland bog, heath and grassland communities were lost between 1950 and 1980.

The forces in the countryside which caused these losses were by no means new. Similar activities had been transforming, and indeed creating, the countryside over the past 200 years. What caused such concern in the early 1980s was the scale and speed of change, and the tiny area of land rich in wildlife which had remained undeveloped. Many of the richest wildlife sites in Britain are those maintained by traditional forms of land husbandry. These include pastures which have not been ploughed up, treated with herbicide and artificial fertiliser and reseeded, old meadows still cut for hay and not silage, areas of downland or unimproved upland pasture, woodlands where deciduous trees are still grown, and upland ecosystems not planted with tracts of conifers. It is not man’s use of the land which automatically destroys wildlife interest, but the form, and especially the intensity, of that use. Intensive afforestation and the relentless drive for greater output and efficiency in British agriculture have in their way been as effecitve in reducing the conservation interest of the countryside as the spread of industry and housing. However, they have affected a far larger area.

The conservationist today is in rather the same position as the farm labourer in the countryside of 200 years ago. He (or she) has few legal rights in the countryside, but has very real interests in the way the land is managed. He may no longer need grazing or fuelwood, but does need attractive landscapes and rich wildlife habitats. These are no less important products of the countryside than the farmers’ crops, although they are less easily valued and sold. Modern agriculture and forestry have damaged those interests to an unprecedented extent, especially since World War II.

The representatives of farming organisations often like to argue that farmers are the original (and best) conservationists. This may be true in terms of agricultural resources (although there are many who would question the ecological sustainability of chemical farming techniques), but it has certainly not been true in terms of nature conservation in the past three decades. None the less, the image persists. A statement from a 1985 government paper responding to a Report of the House of Commons Select Committee on the Environment is typical, stating that ‘most of what we now think of as the most attractive in the farmed landscape is the result of farmers responding to economic and technical pressures in the past’. Certainly it is true that change in the countryside has been brought about over a period of hundreds of years by individual farmers locked into an economic system which forced them to intensify production. Many farmers have found themselves caught in a high-input high-output treadmill. It is far less certain that this has been beneficial for farming (smaller farmers in particular have suffered), and certainly it has been damaging to the countryside and wildlife. Nicholas Bonsor MP said in a committee debate in the Commons in 1985 ‘When I look at the farming background in this country – and I declare my interest as a farmer – I see the enormous changes which have taken place since the war that have been wholly detrimental to the interests of conservation and the interests of agriculture and farming as a whole’.

Agriculture has moulded the countryside, and its own turbulent changes in fortune have had extensive repercussions in natural and semi-natural areas. Farmers are not conservationists: historically they are pawns and pieces on a turbulent chessboard. They have created a countryside as much by what it is unprofitable to do as by deliberate action.

Despite appearances in the past ten or twenty years, farmers have not always been prosperous. There have been periods of depression and bust in British agriculture, as well as booms. The fates of natural and semi-natural habitats in the countryside have been inextricably tied up with these swings in fortune: in the booms, agriculture has expanded onto new land and intensified, and semi-natural habitats have been lost; in the depressions land has been fallowed. But these changes have not balanced each other out over time. Abandoned agricultural land does not suddenly regain its wildlife interest. Many ecosystems take many decades or even centuries to recover. There has been a ratchet at work, so that each progressive change involves further environmental transformation. Under the pressure of agricultural change, the countryside has become less attractive, less diverse in ecological terms, and (because both technological improvements and depressions caused farmers to sack labourers or not replace them), less lived in. As more demands have been made for recreation and access to the countryside by town dwellers, and increasingly for an agricultural landscape rich in wildlife, the countryside has become progressively less able to meet them. Former states are irrecoverable: the ratchet has turned, the pawl clicked home. The changes which have occurred seem to be more or less irreversible.

Of course, the relative wealth and leisure which allows us to want the intangible goods from the countryside – like the chance to see wild plants and animals – cannot be completely separated from the destruction of the countryside itself in the name of progress. There is a bitter irony here, but no inconsistency. We may all have benefited to some extent from the transformation of the countryside, and we have certainly increasingly encouraged the government to fund its destruction, but that does not make the desire to halt the damage invalid. Indeed, the dependence of the agricultural industry on subsidies paid by an overwhelmingly urban population makes their claim for a say in the way the land is used entirely appropriate. Food production is increasingly being seen as just another economic activity, not some sacred duty, and the urban taxpayer seems to be increasingly of the opinion that he who pays the piper should be allowed to call the tune. It is not illogical to want to reverse the trend of intensification in countryside land use, and that is what the conservation movement is currently trying to do. This book is about the simple question: how can the loss of wildlife habitat be stopped? But before tackling that we must examine the pattern of past changes in the countryside in more detail.

Improving the countryside

In 1848, 180 years of government protection for grain farmers ended when the Corn Laws were finally repealed. Despite the dire predictions of landowners, corn prices remained high for the next two decades, and between 1850 and 1870 farm incomes doubled, farm rents rose by a fifth, and rural labourers’ wages began slowly to increase. Most farmers were tenants, but the real profits lay with land ownership. Landholding was excessively concentrated. A survey in 1873 claimed that there were a million landowners in England and Wales, but of these 0.7 million held less than one acre (0.4 ha). Just 1700 large landowners held over 14 million acres (5.6 million ha) between them.

The British population had doubled from the beginning of the 19th century to almost 21 million people by 1850, and it continued to rise. In 1850 almost half the population still lived and worked in the countryside. Although agricultural output increased through the 19th century (rising by between 50 and 80% between 1830 and 1880, for example), from the mid-century onwards the agricultural workforce began to decline in absolute numbers for the first time ever as machinery supplanted hand labour. The industrial population in urban areas rose rapidly.

The previous two centuries had seen fundamental and far-reaching changes in agriculture and the British countryside. Many innovations such as new fodder crops and crop rotations were introduced. Most had little or no distinguishable direct effect on wildlife. The improved methods still allowed a wide variety of species to coexist within the farmed landscape on fallowed land, rough grazings and woods, while substantial areas of undeveloped wild land remained in many parts of Britain. However, one development which did have a considerable effect was the enclosure movement.

From the middle of the 18th century, the old open field system in which different landholders held scattered strips of land in large fields gave way in lowland England to an enclosed landscape. Enclosure, which allowed each landowner to have his land in a single block, made the intensification of production much easier and more rewarding. Slowly at first, and then over extensive areas, larger landowners sought Acts of Parliament to enclose fields and common land. By 1793 over 1600 Acts of Enclosure had been made, covering a total of over 1 million ha. By 1815 a further 1970 Acts accounted for an additional 1.2 million ha, almost 17% of England. By 1830 a further 15 000 ha had been enclosed.

About the only gain from enclosures in terms of conservation was the establishment of great lengths of boundary hedge in the previously open-field counties of eastern England. These have become important as wildlife habitats only in recent years as small copses and woodlands have disappeared from the landscape. Against this has to be set the loss of extensive areas of semi-natural vegetation, and the increasingly intensive management of the enclosed land.

Enclosure had significant effects on many areas of semi-natural vegetation in the countryside which were held under common rights. Of the 2.3 million ha enclosed by 1830, 0.7 million ha was defined as ‘common’ or ‘waste’ land. Fully a third of the Acts of Enclosure involved waste. Whereas open field enclosure was concentrated in the Midland counties, enclosure of commons was more scattered. Thus over 20% of the counties of Cumberland and Westmorland were enclosed ‘waste’, and there were significant areas in Northumberland, Durham, Yorkshire and Somerset. On Exmoor, a man called John Knight enclosed 9000 ha under a single Act in 1817. A total of 18 000 ha had been enclosed by 1859.

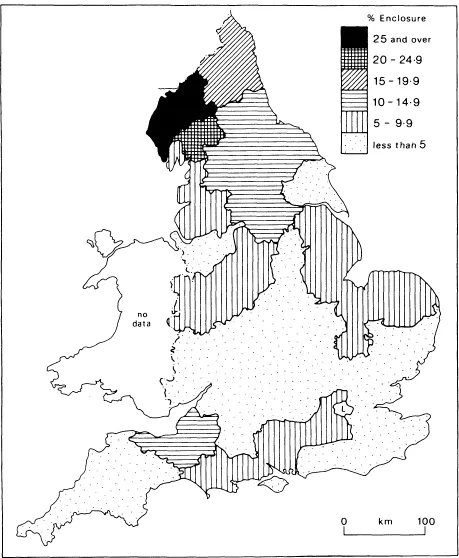

In the 100 years prior to 1880 between 1.5 and 2.4 million ha of waste was enclosed, and much of it reclaimed. Most of this area would now be regarded as important wildlife habitat, but in the late 18th century the prevailing view was that of the agricultural improver Arthur Young, who asked rhetorically ‘what say they to the improvement of moors in the northern counties, where enclosures alone have made these counties smile with culture which before were dreary as night?’. Few influential voices were raised against the enclosures, or against the loss of ‘waste’. In the years of ‘high farming’ of the first three quarters of the 19th century enclosure and improvement continued steadily. Figure 1.2 shows the extent of such enclosure across England, based on the work of Michael Turner on Parliamentary enclosure.

Figure 1.2 The enclosure of commons and wastes in England 1750–1830.

Fenlands were also widely transformed by agricultural improvement. In East Anglia, the first steam pump was introduced at Littleport near Ely in 1819, and fen drainage proceeded apace, perhaps the best-known single enterprise being the drainage of Whittlesey Mere in 1851. This was the last extensive piece of open water left in the fenland, and it was the last known location where the now extinct British race of the large copper butterfly was recorded. Similar drainage work was done in Somerset, where almost 14% of the county was enclosed in the 18th and 19th centuries, a total of 59 000 ha. Acts to drain parts of the Somerset Levels were first passed in 1719 and 1721, and by 1859, 62 Acts accounted for 24 000 ha enclosed and drained.

In 1848, the government announced that it would give loans at low rates of interest for land drainage. The concern here was not the drainage of fenland (although this continued), but the underdrainage of heavy clay soils to make ploughing and arable cultivation possible. The £2 million allocated was exhausted almost at once, as was a further £2 million voted in 1850. By 1864, a total of £8 million had been spent by the Treasury and private investors on land drainage. The figure rose to £12 million by 1878 under the Land Drainage Act of 1861 and the Land Improvement Act of 1864. The ecological impact of this drainage was considerable. The decline of wet meadow butterfly species such as the marsh fritillary began at this period.

However, improvement was not always easy, and some other areas of the country proved more intractable. The Bagshot Heaths in Surrey (still surviving, although much degraded and fragmented) needed to be fertilised with horse manure, and deep ploughed to break up iron pans. It was costly and unremunerative work, and some at least of the enclosed land was left undeveloped: an area of 1600 ha enclosed at Windlesham in 1814 was still largely heath, plus a few plante...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface and acknowledgements

- List of tables

- Acronyms and abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 The changing countryside

- 2 Public interest in private countryside

- 3 Conserving the countryside

- 4 The Wildlife and Countryside Act

- 5 The SSSI system

- 6 Conservation, money and the land

- 7 The conservation of nature

- Appendix

- Index