- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Males With Eating Disorders

About this book

First published in 1990. The subject of anorexia nervosa and, more recently, bulimia nervosa in males has been a source of interest and controversy in the fields of psychiatry and medicine for more than 300 years. These disorders, sometimes called eating disorders, raise basic questions concerning the nature of abnormalities of the motivated behaviors: Are they subsets of more widely recognized illnesses such as mood disorders? Are they understandable by reference to underlying abnormalities of biochemistry or brain function? In what ways are they similar to and in what ways do they differ from anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in females? This book will be of interest to a wide variety of people—physicians, psychologists, nurses, social workers, occupational therapists, nutritionists, educators, and all others who may be interested for personal or professional reasons.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

PsicologiaSubtopic

Psicologia anormaleTreatment and Outcome

9

Diagnosis and Treatment of Males with Eating Disorders

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of males with eating disorders (EDs) is usually a straightforward process, but as with appendicitis, you have to first think of it as a possibility. Accurate identification of anorexia nervosa (AN) or bulimia nervosa (BN) in males has been neglected for primarily two reasons: (1) because of its statistical scarcity, it is not as familiar to clinicians as eating disorders in women and so may not be recognized when it does occur; (2) theoretical biases in some diagnostic methods preclude it from existence. Some psychiatric formulations maintain, for example, that males cannot develop these disorders because they do not manifest a particular required psychodynamic theme, such as fear of oral impregnation, or because they do not have the amenorrhea required by some criteria.

The essential diagnostic criteria for AN may be summarized by the simple threefold requirement described by Russell: the behavior of self-induced starvation; the psychopathological fear of becoming fat that is out of all proportion to reality; and a biologic abnormality in reproductive hormone functioning which could apply to both men and women (Morgan & Russell, 1975). DSM-III-R gives somewhat more quantitative criteria for AN than Russell does by requiring specifically a loss of 15% in body weight, as well as amenorrhea for three cycles in the female, without specifying an analogous reproductive hormone-related change in the male (American Psychiatric Association, 1987). The fact that the weight loss required for diagnosis of AN has diminished from 25% in DSM-III to 15% in DSM-III-R reflects the changing and essentially arbitrary nature of these quantitative criteria, rather than any change in the fundamental diagnostic requirements. From a clinical viewpoint, an individual can be considered to have AN, whether male or female, if a substantial amount of weight has been lost leading to a final state of being medically underweight, in the presence of an inappropriate fear of obesity, and in association with an abnormality of reproductive hormone functioning. Even this latter requirement may be nonspecific and may merely reflect substantial weight loss. Anorectics who not only restrict food intake (ANR) but also experience binge eating are usually referred to as having anorexia nervosa with bulimic complications, or as having AN, bulimic subtype (ANB).

TABLE 1 Diagnostic Criteria for Anorexia Nervosa*

| A. | Refusal to maintain body weight over a minimal normal weight for age and height, e.g., weight loss leading to maintenance of body weight 15% below that expected; or failure to make expected weight gain during period of growth, leading to body weight 15% below that expected. |

| B. | Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though underweight. |

| C. | Disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight, size, or shape is experienced, e.g., the person claims to “feel fat” even when emaciated, believes that one area of the body is “too fat” even when obviously underweight. |

| D. | In females, absence of at least three consecutive menstrual cycles when otherwise expected to occur (primary or secondary amenorrhea). (A woman is considered to have amenorrhea if her periods occur only following hormone, e.g., estrogen, administration.) |

* Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed. rev.). Copyright © 1987 American Psychiatric Association.

Similarly, for bulimia nervosa, the process of diagnosis is relatively uncomplicated if the patient is open and honest on interview. In contrast to AN, which is a publicly visible disorder, BN is often a private and secretive disorder and usually requires cooperation from the patient to make a diagnosis. The term “bulimia” derives from the Greek words for “ox” and for “hunger.” Diagnosis of BN, therefore, usually requires a history of ingestion of large amounts of food (often concentrated sweets and fats), eaten rapidly, against one’s initial resistance and which is typically followed by feelings of being out of control, as well as by depression or guilt. There is a nonproductive debate between those who advocate using subjective criteria for a binge having taken place (i.e., a patient perceives he has eaten in an out-of-control manner) and those who advocate “objective” criteria for the definition of a binge, for example that a certain number of calories of high density food be ingested in a defined period of time.

TABLE 2 Diagnostic Criteria for Bulimia Nervosa*

| A. | Recurrent episodes of binge eating (rapid consumption of a large amount of food in a discrete period of time). |

| B. | A feeling of lack of control over eating behavior during the eating binges. |

| C. | The person regularly engages in either self-induced vomiting, use of laxatives or diuretics, strict dieting or fasting, or vigorous exercise in order to prevent weight gain. |

| D. | A minimum average of two binge eating episodes a week for at least three months. |

| E. | Persistent overconcern with body shape and weight. |

* Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed. rev.). Copyright © 1987 American Psychiatric Association.

In fact, a continuum of bulimic behaviors exists between the extremes of the basically anorectic male with mild bulimic complications, who feels he has binged when he has eaten an extra salad against his will, and the other extreme of a normal weight bulimic who may ingest 8-10,000 extra calories of nutritionally dense food in a short time. We have found in our clinical experience wide variations in the extent of pre-ingestive struggle against appetite, and virtually every possible different amount, kind, and rate of food intake eaten by different bulimic individuals. The essential criteria for BN are, therefore, that binge eating takes place; that the binge eating makes the patient feel he is out of control and in danger of becoming fat; and that he feels he must compensate in some manner for the unwanted calories ingested, whether by self-induced vomiting, strenuous exercising, subsequent fasting, or abuse of laxatives/diuretics, etc.

The recently revised diagnostic criteria of the American Psychiatric Association for BN as described in DSM-III-R compared to those of DSM-III represent a helpful change by now specifying the frequency of binge episodes that must be present before a diagnosis of BN is allowed: an average of two binge eating episodes a week for three months (American Psychiatric Association, 1987). This quantitative requirement helps exclude from the bulimia nervosa diagnostic category any episodes of experimental binge eating, occurrences of short-term “copycat” bulimic behavior, or other transient abnormalities of eating behavior that do not deserve a diagnosis of true BN.

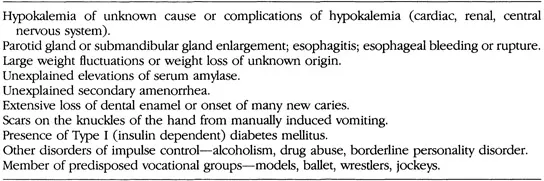

TABLE 3 Clinical Clues to Secretive Bulimia Nervosa

A common diagnostic error, incidently, is to use the term “bulimia” for a male who only induces vomiting of food but has not first eaten in a binge manner. The term BN is appropriately reserved for those males who first binge (bulimia = ox + hunger) whether or not they purge afterwards. On the other hand, the absence of self-induced vomiting or other mode of purging after binge behavior does not exclude a diagnosis of BN, if the required binge-eating and morbid fear of fatness are present.

Males who have an abnormality of eating behavior associated with the psychopathological fear of fatness but who do not meet full DSM-III-R criteria for either AN or BN are given the diagnosis of an “atypical” eating disorder or, more specifically, “Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified” (DSM-III-R: 307.50). Table 3 summarizes some of the signs of secretive bulimia that may alert the clinician to further inquire about the presence of hidden bulimic illness. Unexplained hypokalemia in a young person, rapid and frequent fluctuations in weight, and unexplained erosion of dental enamel are among the common medical tip-offs to undisclosed illness.

Why Diagnosis in Males Can Be Confusing

Eating disorders in males do occur less frequently than in females and this fact alone inclines the clinician to be less likely to even think of it as a diagnostic entity. There is a widespread but misleading stereotype of the kind of person who develops an eating disorder: young, white, upper middle class, and female. This stereotype may lead clinicians, especially those not accustomed to routinely treating disorders, to miss the diagnosis when it does occur, as it so often does, in older women, in minorities, or in males of any age.

Diagnosis in males can also be confusing because the clinician may find an increased incidence of males with eating disorders in a very different subset of the population than those commonly associated with a high incidence in females, such as ballet students (Garner & Garfinkel, 1980) or models. In males, for example, eating disorders occur more often in athletes, especially those whose sports demand weight control, such as wrestlers, jockeys, runners and swimmers. Also, males more often diet defensively when a sports-related injury takes place because of fear of weight gain from inactivity subsequent to injury. Further empirical research is needed to identify additional subgroups of males in which eating disorders occur at a higher than expected frequency so that early diagnosis can be made and preventive efforts can be implemented. Eating disorders appear to have an increased incidence in the subgroup of homosexual males, but no comparable observations have been made in homosexual females. (See Chapter 4 on sexuality.)

Diagnosis in males may additionally be confusing because the terms they use to express conflicts regarding body shape and size may differ from those commonly used by females. Men, for example, rarely complain about the number of pounds they weigh or the size of the clothes they wear. They are, instead, intensely worried about perceived abnormalities in body shape and form, and express intense desire to lose “flab” and to achieve a more classical male definition of muscle groups. We have not observed in males anything comparable to the psychological trauma some women suffer in going from a size 3 to a size 5, for example, or the overinvestment in a certain number of pounds, like staying in the “double digits” in weight, below 100 pounds.

Diagnosis of eating disorders in males may be further obscured because the reasons males give for dieting may sound on the surface medically plausible and even sensible. A subgroup of males in our clinical series heard warnings directed toward one of their parents that the parent should lose weight in order to improve the symptoms of a medical illness suffered, such as heart disease, diabetes, etc. A number of the males in our series who developed eating disorders personalized these warnings directed toward their parent and began to defensively diet to avoid for themselves the dire fate predicted for their parent because of excess weight.

For reasons that are not yet clear, women who go on to develop eating disorders very seldom begin to diet from fear of present or potential future medical illness. We have seen only one case in several hundred women who did diet to avoid a possible medical disease (and this was a woman in her 50s), but it is at least a not infrequent cause for dieting in men. We have reasoned that the male with eating disorders who defensively diets to avoid illness may have more obsessional traits, but this has not been empirically confirmed.

Another reason for diagnostic confusion in males is that the reproductive endocrine manifestation of eating disorders has no analog to the “on/off’ criterion of amenorrhea in females. Testosterone gradually decreases in males with eating disorders and sexual function also gradually decreases pari passu. There is no equivalent step-like change in endocrine function in the male that triggers the same concern in parents and physicians that amenorrhea (primary or secondary) does in a female patient.

In summary, diagnosis of eating disorders in males may be accurately and promptly made by remembering that: a) eating disorders do occur in males, and b) the basic diagnostic criteria for males and females are similar, but the words boys and men use to describe their concerns for body shape and size and their reasons for dieting may differ from the terms girls and women use for the reasons they diet. Furthermore, males with eating disorders, when compared to females, often belong to different vulnerable subgroups that may predispose them to excessive dieting and the pursuit of thinness.

Treatment: Background

The Nature of the Eating Disorders

Treatment of an illness should grow rationally from the clinician’s understanding and conceptualization of the nature of the illness. It is therefore important to have a comprehensive and scientific understanding of the eating disorders (to the extent this information is available) in order to adequately treat these patients. Narrow concepts of etiology based on the belief that the eating disorders spring solely from a single abnormality of neurochemistry, from a specific abnormal family dynamic, or from a particular preexisting disease such as depressive illness will lead logically but unfortunately to restricted treatments that fail to appreciate the global nat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributor

- Preface

- SECTION I: HISTORY, SOCIOCULTURAL STUDIES, AND PSYCHOLOGICAL FUNCTIONING

- SECTION II: CLINICAL AND PSYCHOMETRIC STUDIES

- SECTION III: TREATMENT AND OUTCOME

- SECTION IV: INTEGRATION

- Subject Index

- Name Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Males With Eating Disorders by Arnold E. Andersen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicologia & Psicologia anormale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.