![]()

Part 1

International context of Indigenous education

![]()

Chapter 1

Indigenous education in complex, globalised, postcolonial states

Since 1788 the Aborigines of Australia have been subjected in varying degrees to an education system which has aimed to rationalise their dispossession from the land, deprecate their culture and, in general, endeavour to make the Indigenous people of this country lose their own rich cultural background and think, act and hold the same values as middle-class Europeans.

(National Aboriginal Education Committee (NAEC) 1977)

Introduction

From the 1500s, the education of Indigenous peoples who live in nation states formed during this most recent period of global colonisation by European powers has been a complex matter. The issue of who has the authority to lead and manage education is even more fraught. The emergence of an international rights mechanism, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (United Nations 2008), has at its heart a challenge to nations built through colonisation to move from an institutionally embedded colonial legacy of educating Indigenous populations to ‘fit in’ with imposed, new, nation state arrangements to recognising the sui generis rights of Indigenous peoples and, of particular interest in this book, to issues surrounding the leadership and management of education (Memmi 1967). The term sui generis is being used in the sense that Indigenous peoples have cultural and intellectual property rights that are inalienable (which means that they are not extinguished by later legal frameworks; for further discussion, see Janke 1998).

For Indigenous peoples the problem is twofold. First, a particular type of colonial education has historically been forced on Indigenous peoples who are living in nation states that have formed around them, with the aim of extinguishing pre-existing education practices of Indigenous peoples and supplanting them with what are now familiar forms of teaching young people across the planet. Second, following the first, is that the standard of education available to many Indigenous children is of a poorer quality than what many non-indigenous children would have experienced. As Langton and Ma Rhea (2009) argued, apart from notable exceptions, this imposed form of education was, and continues to be, of such poor quality that there is now a crisis spanning many generations of education failure in many places in the world.

This book brings together the academic fields of educational leadership, educational administration, strategic change management and Indigenous education in order to provide a critical, multiperspectival, systems-level analysis of the leadership and management of education services to Indigenous people. Drawing on a range of theorists across these fields internationally, and mobilising social exchange and intelligent complex adaptive theories to the key problematic of systemically embedded, and arguably racially determined, failure, the book aims to add strength to the argument for an Indigenist, rights approach to nation state provision of education to Indigenous peoples that includes recognition of the human rights of Indigenous peoples as fundamental, and specifically their distinctive economic, linguistic and cultural rights within complex, globalised, postcolonial education systems (Rigney 1999).

The book problematises the concept of partnership between Indigenous and non-indigenous people who are school leaders, teachers, education paraprofessionals and government policy makers and administrators even as it holds this key concept at its centre. The extent to which governments can resist infantilising Indigenous communities, and Indigenous people can re-establish ownership of the education of their children in the nation state, is at the heart of the problematic that this book seeks to address.

The main themes are:

• an internationally relevant, rights-based examination of the administration of state-provided education for Indigenous children

• a systems-level analysis of the provision of education services to Indigenous people

• an integrated, strategic leadership and management approach to the development of partnerships between Indigenous and non-indigenous people about education.

The objectives are:

• to provide a theoretically grounded argument for a multiperspectival, systems-level analysis of Indigenous education

• to offer a sustained critique of linear approaches from educational administrators, policy makers and schools to improvements in education outcomes

• to employ social exchange and complexity theory to examine the development of an equal partnership approach to the leadership and management of Indigenous education.

The book will make the argument for the need for educational administrators of Indigenous education to develop an Indigenist perspective on these matters. This perspective will allow for Indigenous and non-indigenous educationalists to come together to develop a systems approach to leading and managing the education of Indigenous children and also to the education of non-indigenous children about Indigenous rights and lifeways. The Australian education system is large, and the accountabilities have been weak in the Indigenous education area. This approach builds on ideas first presented by Langton and Ma Rhea (2009) in consideration of how Australia might begin to address the emerging Indigenous rights agenda in education (Figure 1.1).

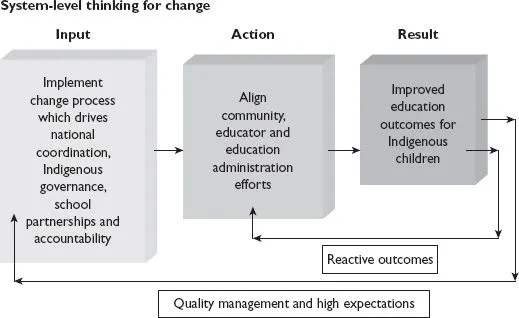

Figure 1.1 Systemic quality assurance thinking (adapted from Langton and Ma Rhea 2009).

In Australia, this requires an Indigenist perspective to be developed within a systems approach to change which clearly identifies the inputs, actions required and expected outcomes as well as incorporating a quality assurance cycle and maintaining high expectations of success. It contains within its logic recognition that single-loop learning, here shown as providing only reactive outcomes, will be insufficient to enable new outcomes to arise.

This approach incorporates what we know to be a successful quality management approach that, by its nature, involves double-loop learning. Inspired by Feigenbaum (1945) and Ishikawa (1985), Total Quality Management (TQM) and later developments such as Six Sigma (Motorola 1986) and Lean Manufacturing (Krafcik 1988) focused on using systems-level analysis to improve quality outcomes in organisations. The usefulness of the approach of double-loop learning to the work of improvement is explained by Argyris and Schön (1978: 2–3):

When the error detected and corrected permits the organization to carry on its present policies or achieve its present objectives, then that error- and-correction process is learning. Single-loop learning is like a thermostat that learns when it is too hot or too cold and turns the heat on or off. The thermostat can perform this task because it can receive information (the temperature of the room) and take corrective action. learning occurs when error is detected and corrected in ways that involve the modification of an organization’s underlying norms, policies, and objectives.

Single-loop learning allows a system, or organisation, to adjust itself incrementally. It is enabled by following set plans and routines. Argyris (1982: 103–104) identifies this as being ‘both less risky for the individual and the organization, and affords greater control’. He explains that double-loop learning is much harder for an organisation to undertake because, by nature, it is ‘more fundamental: the basic assumptions behind ideas or policies are confronted … hypotheses are publicly tested … processes are disconfirmable, not self-seeking’ (Argyris 1982: 103–104).

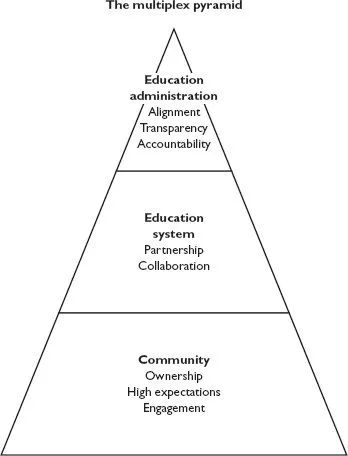

The leadership and management of public service organisations, while different in outcome motive, have usefully drawn on the idea of quality improvement as part of delivering public value to the communities they serve (Moore 1995). This book makes the argument that the enormity and complexity of the task of indigenising an entire education system demand simultaneously addressing community governance and leadership capacity building, culturally appropriate principal, teacher, teacher educator and education administrator professional development, and the leadership and management of policy development in order to address the demands of total quality improvement of education services to Indigenous populations (Figure 1.2). As proposed above and developed throughout this book, the changes will need to identify and agree the inputs, actions and expected outcomes at various levels, as well as incorporating a quality assurance cycle and maintaining high expectations of success. This requires the double-loop learning approach that will be advanced in the following chapters. Critically examining the underlying intentions and commitments of norms, policies and objectives that have sustained the colonial, deficit thinking model of education requires willingness for reflection, expanded modes of thinking and a willingness to experience the discomfort of the unfamiliar.

Like any systems-level problem, issues facing communities, educators and governments in the provision of education services to Indigenous people can appear overwhelming and insoluble. I do not share this view. This analysis will be more fully developed in Part 3.

Who are Indigenous people?

The first thing we need to do is to look at the definition of ‘Indigenous’. It is a highly contested concept internationally and, as we will see, in leading and managing Indigenous education, particularly within postcolonial democratic states. A definition of ‘Indigenous’ ensures that we are speaking about something about which there is international consensus.

Figure 1.2 Quality management of the multiplex pyramid (adapted from Langton and Ma Rhea 2009).

Using the correct terminology is important given the nature of rights accorded internationally to Indigenous peoples as distinctive identities, with deep links with ancestral lands, and having reliance on customary law and institutions (which in many cases are interrelated with the surrounding natural environment), rights which precede the creation of nation states. The United Nations’ Working Group on Indigenous Populations has been using the following definition (proposed by UN Special Rapporteur Martinez Cobo in 1986) to guide its work:

Indigenous communities, peoples and nations are those which, having a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing in those territories, or parts of them. They form at present non-dominant sectors of society and are determined to preserve, develop and transmit to future generations their ancestral territories, and their ethnic identity; as the basis of their continued existence as peoples, in accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions and legal systems.

(Cobo 1986)

Summing up the deliberations of years of work, ten years later, Mrs Erica Daes (1996), the Chairperson of the UN’s Working Group, concluded that:

In summary, the factors which modern international organisations and legal experts (including Indigenous legal experts and members of the academic family) have considered relevant to understanding the concept of ‘Indigenous’ include:

• priority in time with respect to the occupation and use of a specific territory;

• the voluntary perpetuation of cultural distinctiveness, which may include aspects of language, social organisation, religion and spiritual values, modes of production, laws and institutions;

• self-identification, as well as recognition by other groups, or by State authorities, as a distinct collectivity; and

• experience of subjugation, exclusion or discrimination, whether or not these conditions persist.

The International Labour Organization’s Convention No. 169 (ILO169) (International Labour Organization 1989) adopted a definition that includes the rights of both Indigenous and tribal peoples. Its Article No. 1 stipulates that it applies to peoples who are regarded as Indigenous on account of their descent from the populations which inhabited the country, or a geographical region to which the country belongs, at the time of conquest or colonisation or the establishment of present state boundaries and who, irrespective of their legal status, retain some or all of their own social, economic, cultural and political institutions. Article 1(2) stipulates that ‘Self-identification as Indigenous or tribal shall be regarded as a fundamental criterion for determining the groups to which the provisions of this Convention apply’ (International Labour Organization 1989).

International context for Indigenous education

Within an overarching international agreement on a legal definition of Indigenous peoples and, thereby, a recognition of sui generis rights, particular agreements are evolving about the future development of education for Indigenous populations that will have a profound impact on education systems currently provided by nation states. Historically, these conversations have been conducted in parallel universes where bureaucratic nation state representatives argue to protect the interests of the state vis-à-vis their Indigenous populations while Indigenous families, experts and representative organisations attempt to influence the direction and substance of such deliberations through both formal and informal representation.

Various bodies address Indigenous rights and issues through globally agreed conventions such as the International Labour Organization’s Convention No. 169 (International Labour Organization 1989) and the United Nations’ Convention on Biological Diversity (United Nations 1993), mechanisms such as the Declaration on the Rights of the Child (United Nations 1959), Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (United Nations 2008) and more recent strategic policy initiatives such as the Global Compact (United Nations 2000). All make reference to the importance of the role of education as a foundational aspect of their work.

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

The most pivotal document in recent years that is influencing the provision of education services to Indigenous peoples in postcolonial democratic states such as Australia is the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIPs). After 20 years of discussion and debate, it was adopted by the General Assembly Resolution 61\295 on 13 September 2007 (United Nations 2008).

UNDRIPs is a significant change marker in the way that nation states recognise Indigenous peoples within assumed territorial boundaries. Its wording has an impact on the way that matters such as individual and collective rights, cultural rights and identity, rights to education, health, employment and language are dealt with by nation states. The UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) notes in its frequently asked questions (FAQs) document that:

Many of the rights in the Declaration require new approaches to global issues, such as development, decentralization and multicultural democracy. In order to achieve full respect for diversity, countries will need to adopt participatory approaches to Indigenous issues, which will require effective consultations and the building of partnerships with Indigenous peoples.

(United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) 2007)

UNDRIPs recognises and affirms that Indigenous peoples have the right to enjoy fully, as a collective or as individuals, all human rights and fundamental freedoms as recognised in the Charter of the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international human rights law. Indigenous peoples and individuals are free and equal to all other peoples and individuals, and have the right to be free from any kind of discrimination, in the exercise of their rights, in particular that based on their Indigenous origin or identity. Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination. By that right, they can freely determine their political status and pursue their economic...