![]()

1 Introduction

Temporality, Youth, and Nation

Victoria Pettersen Lantz and Angela Sweigart-Gallagher

Nationalism and Youth in Theatre and Performance is a collection of essays that explores two fluid concepts: youth and nationalism. This book brings together international case studies that trace by what means performance by and for youth reflects and redefines national concerns. The contributing scholars and practitioners bring into focus different ways youth factor in the discussion of nationalism and to what extent young people possess agency in their representations and ideas of nationhood.

Who are youth? Youth are frequently described, both colloquially and in childhood studies, in terms of their development, with childhood/youth seen as a period from which a person develops into an adult, physically, mentally, socially, and culturally.1 In other words, childhood is a period of rapid transition that concludes in adulthood. The border between childhood or youth and adulthood is a porous one, with culturally and contextually determined boundaries. Nonetheless, that border, however wide, constructed, and indeterminate, exists.2

Even organizations tasked with creating international guidelines and definitions struggle to pin down not only what youth is but also when it begins and ends. On a webpage titled “What Do We Mean by ‘Youth’?” UNESCO suggests that “youth is a more fluid category than a fixed age group.”3 In its efforts to maintain statistical consistency and elide regional and national idiosyncrasies, the United Nations (UN) defines “youth” as persons between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four years, and for the purposes of its Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), the UN defines “child” as any “human being below the age of eighteen unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier.”4 According to international guidelines, then, age limits defining the terms “child” and “youth” overlap.

For the purposes of this collection, we consider “youth” to encapsulate, although not to erase, the category of “child.” As a whole, Nationalism and Youth in Theatre and Performance analyzes performances by, with, and for a wide range of ages within the broader category of youth. Individual chapters, however, tend to explore much narrower age groups, and contributors use the term most appropriate to their particular study. What links all of the chapters in the collection is the way in which each situates youth at the center of the intersection of theatre/performance and nationalism.

As Amílcar Antonio Barretto observes in Nationalism and Its Logical Foundations, “as a field of academic study, nationalism suffers from a lack of scholarly consensus” that is “notorious for resonating like cacophonous dissonance.”5 While we do not propose to enter this fractious debate with a singular answer or definition, most of the contributors in this collection approach nationalism from a perspective similar to that of Katherine Verdery, who argues that nationalism is the “political utilization of the symbol nation through discourse and political activity, as well as the sentiment that draws people into responding to this symbol’s use.”6 By drawing attention to the symbol nation, Verdery’s definition allows for the possibility that nations may exist as symbols only, or exclusive of geopolitical nation-states, an issue explored by some of our contributors. However, her definition also suggests that for the symbol nation to be politically useful it must be recognizable to its members, making a common culture, set of traditions, or history—important features of nationalism that might be described as composing national identity.

Youth and nationalism intersect in the need to carry forward this symbol nation. Youth is, in fact, central to the definition and perpetuity of nationalism, particularly as nationalism is often defined in generational terms. As Steven Grosby explains, “The child learns, for example, to speak the language of his or her nation and what it means to be a member of that nation as expressed through its customs and laws. These traditions become incorporated into the individual’s understanding of the self.”7 The child learns national identity through customs and rituals, and in turn preserves, reproduces, and ultimately revises those traditions by continuing to enact them into adulthood. The process is not guaranteed to be continuous, as individual children must disseminate institutional, communal, and familial modes of national identity to create their own set of values. Youth and nation are ideas in flux, and factors like immigration, regionality, religion, diaspora, and globalization all inform and transform them.

The unifying factor in engaging the collective consciousness of a nation is performance. Daily rituals, like reciting pledges and the way in which we eat or dress,8 as well as grand-scale communal customs such as inaugurations, are public performances of nationhood. These performances may not be intended solely for youth participants or audiences, but they do have an educational or institutional function for both adult and youth spectators. An understanding of nationalism, then, requires a consideration of how youth enact, embody, or engage with the nation. Our own experiences as American youth illustrate how pervasive moments of enacted nationalism are in daily routines. We therefore offer these two personal anecdotes to underscore some of the ways youth perform nationalism.

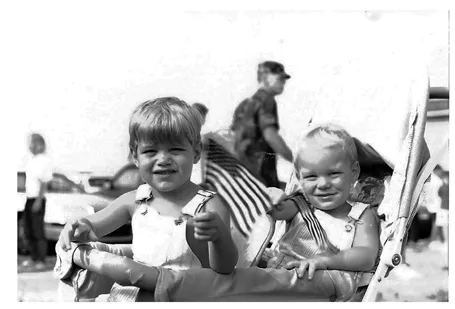

“YOUNG, PATRIOTIC WELL-WISHERS” AND “TO THE COLORS”—ANGELA SWEIGART-GALLAGHER, ARMY BRAT

I was born and grew up on (or near) U.S. Army bases. As a young person, I engaged in numerous nationalistic performances simply by virtue of participating in the routines (both the daily and the exceptional) of life on an Army base. Along with my siblings, I tearfully waved small American flags and sang along as a live band played the national anthem in an airport hangar when my father departed to Operation Desert Storm. Our singing and flag waving so crystallized the national pride of the moment that a photograph of my then-toddler brothers ran in the local paper with the caption “Young, patriotic well-wishers show their support.”9 While this performance was one of the more exceptional moments in which I was asked to enact nationalism as a youth, even the more mundane aspects of life on an Army base required engaging in performances of nationalism and national identity.

On all U.S. Army bases, residents mark the end of the duty day with a distinct ritual in which a bugler sounds “Retreat” followed by “To the Colors” as an honor guard lowers and retires the American flag for the day.10 It is not only customary but compulsory for anyone outside during the end-of-day ceremony to participate, regardless of age or occupation. Soldiers in uniform must salute the flag, anyone driving on base is expected to come to a stop, and even civilians (including youth) are expected to participate by standing quietly until the flag ceremony is over. I learned to participate in this performance through a combination of modeling and direct instruction. I observed my father salute the flag while in uniform and watched as my mother stopped loading the groceries into the car in order to stand quietly. My siblings and I were reminded to “stand still,” “be quiet,” or “take off your hat.” That I learned to participate in this performance is a reminder that youth learn to perform national identity and nationalism, through both informal and formal means, through families and institutions such as theatres, festivals, schools, and camps—all sites explored in this collection.

Figure 1.1 “Young, patriotic well-wishers show their support.” This photo is one of a series taken of Angela Sweigart-Gallagher’s brothers on September 8, 1990, the day their father deployed. Photo courtesy Robert Sweigart.

My participation in this relatively mundane ceremonial performance grew more complex during our tours overseas. I distinctly recall walking across Leighton Barracks in Würzburg, Germany, where my father was stationed from 1991 to 1994, and stopping to mark the end of the duty day. Just as I had “in the states,” I, along with everyone else, froze in an act of patriotic reverence for a metonym of our national identity. The shared ritual of the flag ceremony allowed us to connect with a sense of national belonging and pride even while living and working abroad. It allowed us to bring America into being, or, to appropriate Ernest Gellner’s formulation, our performance of nationalism invented the nation where it did not previously exist, creating a relatively small territory of “America” within the larger context of “Germany.”11 As long as we remained within the gates of the base, we were legally, as well as imaginatively, in America.

What I failed to fully appreciate at the time is the way in which this performance also functioned militaristically. Not only did the flag ceremony instill a sense of “collective self-consciousness”12 and discipline in all who participated (as it compelled us all to engage in similar if not identical actions), but it also served to militarize the participants, including civilians and youth simply living on base. Even without a weapon, we (soldiers, civilians, adults, and youth) claimed the space of Leighton Barracks as a small piece of America within Germany every night through our collective performance of American nationalism. What made it even more strange (and perhaps more aggressively nationalistic) was that the flagpole at which this ritual was performed was located near the base’s entrance; on the other side of the gate were apartment buildings that housed local Würzburg residents. That the German community members who surrounded the base could see and hear our performance of patriotism and ceremonial claiming of territory never struck me as odd at the time, but certainly seems jarring in retrospect. They (the Germans) must have heard the bugle calls and possibly even seen us stop our daily comings and goings to perform this act of militaristic nationalism; they heard and possibly watched as we symbolically claimed German territory in the name of America.

“ON MY HONOR”—VICTORIA PETTERSEN LANTZ, GIRL SCOUT

Most of the summers of my childhood were spent at Camp Arrowhead on the Washington side of the Columbia River Gorge. A residential Girl Scout camp, Arrowhead is a place for girls ages seven through eighteen from around Oregon and Washington to learn outdoor skills and Girl Scout values. I was so devoted to the camp that as an adult I returned to it as a counselor. Part of my love of this camp was its commitment to performance as a community-building tool. At Arrowhead, we performed individually and as groups at campfires; sang before, during, and after every meal; and ended the day singing “Taps.” Camp, for me, perfectly cemented the empowerment aspect of the Girl Scouts as an organization: “In [Scouts], girls discover the fun, friendship, and power of girls together.” By the end of the summers, I did in fact feel “courageous and strong.”13

The Girl Scouts, as an American institution founded in 1912, not only aims to help girls form strong bonds and commitments to serving communities, but also aims to promote a patriotic value system focused on embodying America. Both as a camper and as an adult, I participated in the posting- and retiring-the-flag ceremonies, in which units of girls took turns acting as color guard. Every morning and evening, units of campers met at the flagpole after dinner. The “caller” brought forth the color guard, then issued commands such as “Color guard, honor your flag” (followed by a salute) and “Color guard, post/retire the colors.” The ceremonies at Arrowhead were somber proceedings with six girls lowering, removing, and folding the flag in unison into a triangle, while other members of the unit and counselors watched.

For me, it was always exciting to be among the color guard because it meant being part of a staged group performance. Even though I liked following the specific gestures and codes in the rituals along with the other girls, I was not a diehard Scout. After the age of twelve, I did not have a troupe, wear a uniform, sell cookies, or earn badges during the year, but during summer, I took on the role of Girl Scout, and the flag ceremonies were and are fundamental to how the Girl Scouts, as an organization, define their group identity.

As a half-time Scout, I did not fully engage with the history of the...