![]()

1

Aging, Pensions and Social Security in South Asia

S. Irudaya Rajan

The aging of populations is one of the glaring consequences of demographic transition. Having already begun to experience these consequences, the developed countries of the world have developed policies and programmes to avert crises and promote economic growth. Developing economies such as South Asia are also well on their way along a similar course, and are either prepared to face the consequences or to manage the growing numbers of the elderly through appropriate policies. Although the proportion of the elderly who are 60 years of age and above would seem relatively low in the most populous regions of the world such as China and India, in terms of absolute numbers these countries have more elderly persons than many other nations because of their large population bases. The emphasis laid in recent times on studies related to the elderly in the developing world is attributed not only to increasing numbers, but also to deteriorating living conditions of the elderly, accentuated in part by the rapid processes of modernization, urbanization and migration. The projected increase of the elderly populations in both absolute and relative terms is, in many developing countries, a subject of growing concern for demographers, planners, policymakers, acturial experts and pension economists; it has indeed been a matter of grave concern for countries such as India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh (Chakraborti, 2004; Government of India, 1999, 2001; Irudaya Rajan, 2000, 2001a, 2001b; Irudaya Rajan and Mathew, 2006; Irudaya Rajan et al., 1999; Irudaya Rajan et al., 2006; Liebig and Irudaya Rajan, 2003; Mahmood et al., 2006; Perera and Gunawardena, 2006; Rannan-Eliya et al., 1998; Rodrigo, 2000; Treas and Logue, 1986; World Bank, 1994, 2000, 2001).

Population Aging

The world’s population is expected to increase to 9.4 billion by 2050 from the current 7.3 billion. During the same period, the proportion of the elderly population is expected to increase from 10.4 per cent to 21.7 per cent. Among the elderly, it is the oldest among the old (those aged 80 years or above) whose numbers will increase most rapidly over time, to about 320 million by 2050. The likely scenario of the global population projected by the United Nations (2005) for the period 2005 to 2150 is presented in Table 1.1. In 2000, the number of children below 15 years of age was estimated to be 3.3 times higher than those aged 60 years and above. For the first time in history, however, the number of the aged is expected to exceed the number of the young by 2050. Another interesting feature observed from the same table is that when the world population is estimated to reach about 11 billion in 2100, almost one in three persons will be an elderly person.

Year | Total population (in billion) | 60 years and above (per cent) | 65 years and above (per cent) | 80 years and above (per cent) |

| 2005 | 7.3 | 10.4 | 7.4 | 1.3 |

| 2025 | 8.1 | 15.1 | 11.2 | 2.4 |

| 2050 | 9.4 | 21.7 | 15.8 | 4.3 |

| 2075 | 10.1 | 26.5 | 19.5 | 6.0 |

| 2100 | 10.5 | 29.2 | 22.5 | 7.5 |

| 2125 | 10.6 | 30.2 | 24.1 | 9.3 |

| 2150 | 10.9 | 31.8 | 25.6 | 10.8 |

Source: United Nations (2005)

Table 1.1 Global Scenario of the Aged, 2005–2150

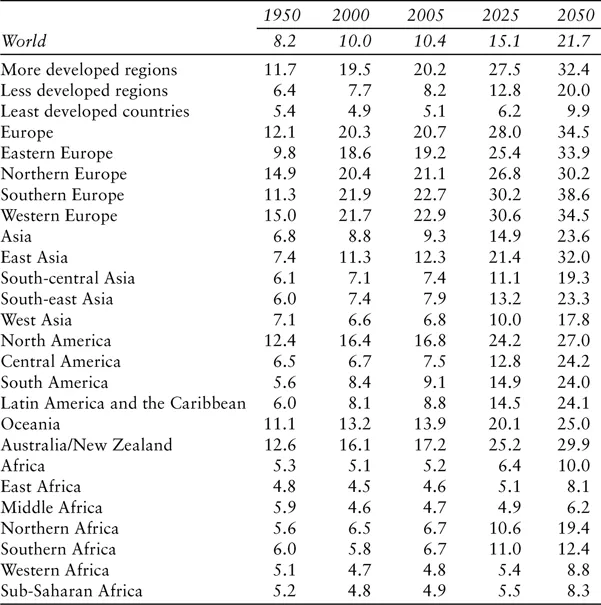

According to the assessment of the United Nations (2005), only Northern and Western Europe had more than 15 per cent of their population in the elderly age group in the year 1950 (see Table 1.2). In 2000, however, all the regions of Europe, North America and Australia/New Zealand had crossed the 15 per cent mark. Further, in the more developed regions among them, the corresponding proportion had risen to about 20 per cent. In the next fifty years, the proportion of the aged is expected to grow more rapidly with Asia almost reaching the 15 per cent level. As of today, Southern Europe has the highest proportion of the elderly in the world and it is expected to reach the level of 38.6 per cent by 2050. In the developing countries, one in every twelve is now an elderly person and the ratio is expected to become one in five by 2050. In the developed countries, the ratio is already one in five and is projected to become one in three by 2050.

Source: Same as Table 1.1.

Table 1.2 Aging in Major Regions of the World, 1950–2050

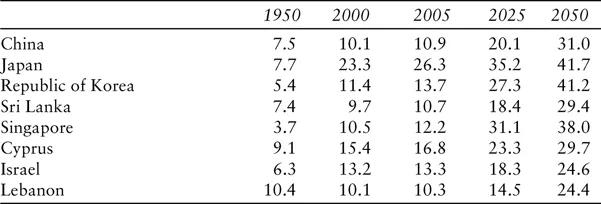

In Asia as a whole, the elderly make up only 9 per cent of the population, but there are significant variations across countries and regions. As of 2000, East Asia leads with 11 per cent of its population in the age group of 60 years and above. One in every ten persons in China is an elderly person; in India, the proportion is one in every twelve Indians. The percentage of the elderly population is expected to rise to 31 per cent in China and 21 per cent in India by 2050 (Table 1.3). Among the other countries in Asia which call for serious attention in terms of policies and programmes for the elderly are Japan, Singapore, Korea, Cyprus and Lebanon. Japan is expected to be the fastest aging population in Asia with about 42 per cent elderly in 2050 (for more details on Japan’s elderly and social policy, see Bass et al., 1996).

Source: Same as Table 1.1.

Table 1.3 Aging Scenario in Selected Countries of Asia, 1950–2050

Among the five South Asian countries (Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka) that are discussed in this book, India is expected to have the largest elderly population by 2025: 158 million (12 per cent), as against 4 million (17 per cent) for Sri Lanka. India already has 90 million elderly persons—a number that surpasses the total population of all but thirteen countries in the world.

In the past, traditional social values and religious observances used to be quite supportive of the elderly in many developing countries. Today, however, economic change, the disappearance of the joint family system and increased mobility are drastically eroding the support base of the elderly. At the same time, institutional arrangements catering to the needs of these people have been few and their coverage limited. The provision of a regular pension is normally limited to former civil servants who make up only a small proportion of the elderly.

Aims and Objectives

Within this broad context, the present book proposes to identify the modalities of a comprehensive pension and social security scheme for the elderly population in South Asia, drawing on the experiences of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal. Each country is discussed in a separate chapter which will address the following issues:

• assess the aging scenario in these countries: past, present and future;

• report the findings of a sample survey in each of these countries conducted for this study in order to assess the nature, magnitude and adequacy of various forms of social assistance now available to the elderly;

• review existing policies and programmes for the elderly; and

• advance suggestions for broad-based comprehensive pension, social security and assistance schemes for the elderly.

In addition to using census reports and other documents published by national and international organizations, a sample survey was undertaken in each of these countries to generate firsthand information regarding problems faced by subgroups of the elderly, such as regular pensioners, family pensioners, recipients of social assistance and elderly persons who receive no outside support.

Socio-demographic Setting in Five Asian Countries

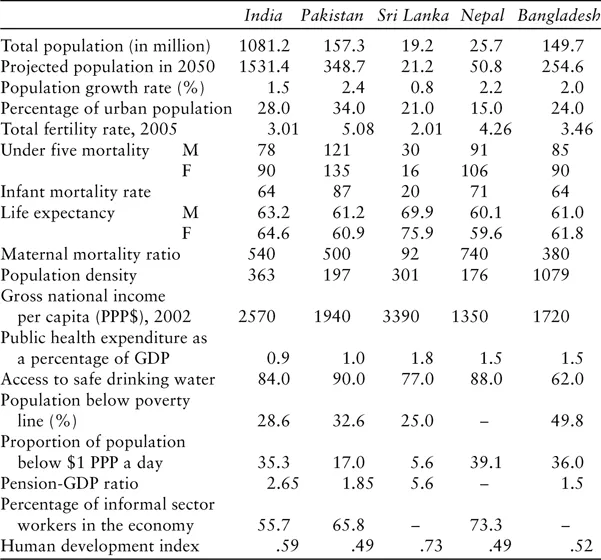

Until recently, most South Asian populations were marked by high levels of fertility and mortality. In the 1950s, fertility across South Asia was uniformly high, but by 2001 Bangladesh, India and Sri Lanka had attained lower fertility rates than Nepal and Pakistan. Fertility in Sri Lanka has already fallen to the replacement level (Table 1.4), and India and Bangladesh are expected to reach that level by 2045–50.

The decrease in mortality is reflected in the increasing life expectancy at birth which is the highest in Sri Lanka. In the 1950s all the South Asian countries had shorter life spans for women than for men (the opposite of global mortality norms), for a variety of reasons ranging from discrimination against girl children to high maternal mortality rates (Razavi, 2000). By 2005 female life expectancy at birth almost equalled or exceeded that of males in all South Asian countries. By 2050 females are expected to outlive males in all the countries of South Asia; in Sri Lanka, the difference between the life expectancy of men and women is expected to be five years.

Source: ILO (2002); UNFPA (2004); United Nations (2005); World Bank (2006).

Table 1.4 Socio-economic and Demographic Indicators for South Asian Countries, 2004

The aging of the population in South Asia will thus proceed faster than in other developing countries. Moreover, the transition from high to low fertility is expected to narrow the base of the age pyramid and broaden it at the top. In addition, improvements in life expectancy at all ages will result in the survival of more old persons, thus intensifying the aging process.

Increasing life expectancy implies increasing numbers of older people and old people living longer lives than their earlier cohorts (Irudaya Rajan and Mishra, 1995). Available statistics indicate that in Sri Lanka in 2005, men aged 60 were expected to live another nineteen years, and those aged 70 years another thirteen years; the corresponding figures for women were twenty-one and fourteen years, respectively. Increased rates of survival beyond 60 years of age have many implications for the financial burden of pensions and social assistance payments on the governments of these countries. Health care financing for the elderly by the individuals themselves, their respective families and insurance companies needs special mention.

Asia accounts for approximately 9 per cent of the world’s elderly. However, the proportions vary across regions. In 2005 East Asia led with nearly 11 per cent of its population being designated as elderly. South Asia, Southeast Asia and West Asia had approximately 7 per cent each. In 2050 almost one in three persons is expected to be old in East Asia, one in five in South Asia and Southeast Asia, and one in six in West Asia (United Nations, 2005). Though India is expected to have the largest population of the elderly in 2050 among the South Asian countries under study, Bangladesh will see the fastest growth rate of the elderly population: the number of the elderly is expected to increase nearly sevenfold in Bangladesh in the next fifty years, but only fourfold in India and fivefold in Sri Lanka. By 2050 one in five people in Bangladesh and India will be an elderly person as against one in four in Sri Lanka. All countries already have more elderly women than elderly men, with the difference between the population of the female and male elderly ranging from 5 to 9 percentage points. Thus, the feminization of aging is also evident in South Asia. Finally, whereas in the next twenty-five years the annual growth rate of the general population in South Asia is expected to be around 1 to 1.5 per cent, that of the elderly is likely to be much higher; India’s elderly population is likely to grow by 9 per cent per year.

Population pyramids for South Asia show a broad base, indicative of a young and growing population (see Figure 1.1). The corresponding pyramids for 2050 for South Asia exhibit a more columnar shape, indicating that the population has grown older. The pattern for Sri Lanka in 2050 (see Chapter 5 for age pyramids of Sri Lanka) suggests that the absolute total population may begin to decline (Sudha and Irudaya Rajan, 2002). The future age pyramids in the South Asian countries (Figure 1.1) will typically replicate those observed in industrial countries today. The process of population aging in the latter set of countries occurred in the midst of greater affluence whereas the developing societies that are experiencing this process today are still steeped in poverty. Providing adequate social assistance and security for the elderly poor in the developing countries will be a major challenge in the near future.

A variety of indicators are in use for assessing the speed of aging, including the median age (the age that divides ...