![]()

Part I

Theorising democracy as a spatial practice

![]()

1 Ancient Greece and the tri-partite model of democracy

This chapter describes the origins of democracy, two thousand years ago in ancient Athens, where democracy was direct or participatory; each citizen had an equal right regardless of their property or class to participate directly in political decision-making through public assembly and not through representation.1

Classical historian M. H. Hansen, discussing the extent to which the Athenian democracy has influenced modern democracy, argues that Athenian democracy was both a set of political institutions and a set of political ideals. For Hansen, it is advisable in an analysis of Athenian democracy to treat the institutions and ideals separately. He argues that, as a set of institutions, there is very little similarity between ancient democracy and modern democracy. As an ideology, the Athenian triad democratia-eleutheria-isonimia, interpreted by Pericles in his funeral oration, has a striking similarity with its modern counterpart, democracy-liberty-equality, but these are unrelated as there is no direct tradition that connects the two.2 In this chapter, I aim to examine the role of public space and the city, and therefore I will discuss the institutions rather than the ideology of Athenian democracy. While the ancient public spaces do not have a relationship with modern democracy, I argue that they can be understood through contemporary political theory, discussed in Chapter 2, and the social forums, discussed in Chapter 6.

For Hansen, Athenian democracy was not just a constitution or a set of institutions but a way of life. For the Greek way of thinking, no constitution could take effect unless it matched the lifestyle of the citizenry. Democracy corresponded to ‘democratic man’ and ‘democratic lifestyle’, but it was the democratic institutions of the polis that shaped and moulded democratic man.3 He states that participation in Athenian democracy involved a number of practices which took place in political institutions: ‘The Greek poleis were characterised by the abundance of political institutions and Athens was in the lead’. He particularly refers to the assemblies and the law courts. Hansen argues that unlike modern democracies where participation is limited to voting for the majority of people, most adult males were involved daily in working for those institutions.4

Classical political theorist Sara Monoson expands the notion of democratic practice to include a multitude of activities, spaces and changing roles of the citizen. She argues that democracy was not seen as something that happens in democratic institutions, which govern and make laws; democratic identity was something fluid and changing. Democracy not only involved participating in the assembly and the council but also involved participating in the demos, where democratic citizenship entailed a cluster of cultural practices. Athletic competition, poetic production, theatre-going or sexual behaviour were as much about democratic citizenship as deliberation in public affairs.5

Hansen argues that the meaning of ancient democracy changed at the end of the eighteenth century, with the advent of modern democracy,6 and it could also be argued that so did the criticisms of Athenian democracy. Hansen states that until 1790, democracy was invariably taken to mean government by the people, over the people, through a popular assembly.7 The ancient democracy referred to was the general type critically described by Plato and Aristotle, who criticised Athenian democracy for, among other things, its inclusionary nature, the rule of ordinary people, artisans, traders, labourers and idlers in contrast to the propertied class. The assembly was a political organ in which the majority poor could outvote the minority of countrymen and property owners.8

Hansen argues that during the first half of the nineteenth century, the appraisal of Athenian democracy changed to an historical analysis from a philosophical analysis, and this was a more positive account.9 However, for David Held, critics of participatory democracy argue that the rise of democracy in ancient Athens coincided with the rise of slavery in mining, agriculture and the craft industries. They argue that citizenship was extended only to adult, male, freeborn Athenians who were citizens and that others were excluded. Men had the free time to participate in the polis because women, slaves, boys and foreigners were confined to the work at home.10 As Habermas writes, ‘the status in the polis depended on status as the master of the home or oikos’.11 Many academics, for example Malcolm Miles, dismiss the democracy of ancient Greece for its exclusionary nature:

This contradicts a more common alignment of public spaces with democracy, projected onto the agora (market) of classical Athens or its equivalent in north American bourgeois democracy. For example the piazza in an urban redevelopment scheme becomes a new agora where new urbanites mix and shape society. This is fanciful in two ways: firstly, because new urban spaces are primarily zones of consumption (often masking zones of corporate power); and secondly, because such a view is contradicted by the historical model – political decisions in Athens were made in the assembly (Pnyx) not the market, and were made only by men born free in the city who owned a talent of silver – maybe 5 per cent of the population.12

Where the exclusion is undoubtedly true in terms of the status of citizen and for the decision-making assembly, the boundaries as to what constitutes the practice of democracy seem to be more blurred, particularly if we take Monoson’s definition of democratic practice. For example, the polis describes all public space; the craft industries were producing items as well as selling them in the agora, where the trade council and associations operated. Nicholas Jones argues that it was through membership and performance in associations that people gained the right to become citizens, and associations may be said to mediate between the state and the individual.13 So it appears that status in the polis depended on performance in the polis as well as the oikos.

It is important to examine the city in ancient Athens because this allows us to imagine a political rather than social14 sense of public space. Democratic participation can be seen to have a different spatiality in antiquity than in modern times, where, for Arendt, modernity has been intent on excluding political man that she defines as ‘man who acts and speaks, from its public realm’.15 The polis of the free and equal referred to citizens and to the parts of the city that were common. Rather than having democratic institutions in the way we have now, public space was political. However, for classical theorist M. H. Hansen, the polis referred to the political sphere and the polis regulated a range of social activities. Matters such as industry, trade, education and agriculture were within the private sphere.16

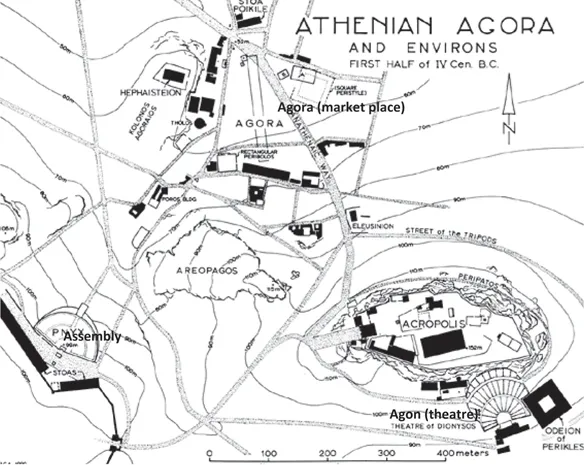

If one looks at the plan of the site of the Athenian agora whose ruins still remain (see Figure 1.1), the word agora is used to describe both the larger site or the political centre of ancient Athens and the market place within the larger space. As I show later in this chapter, the assembly and the theatre started as practices in the market place before they became established spaces. The word agora, meaning the place of assembly, comes from the word agoraomai, meaning to speak in the assembly, extending public speaking to the larger site. Three key, but very different, democratic spaces are the theatre at Dionysus, the market place (the agora proper) and the assembly at Pnyx. These, I argue, operated in a tri-partite way, where the democratic nature of the agora required differing democratic identities relating to the democratic practices.

Figure 1.1. Topographic map and plan of the Athenian agora and environs (Pnyx, Areopagus, Acropolis), circa the first half of the fourth century BC

Monoson’s thesis is that democratic citizenship required differing aspects of the self-image; theatés was the word used to describe the citizen as theatregoer, and being a theatés was a fundamental political act: ‘To attend a play was designed to hear critical speech regarding political matters … and citizens practised important intellectual skills that they would then use in the assembly.’17 For example, Aristophanes’s plays were concerned with issues of communication, persuasion, the nature of leadership and the nature of democratic participation. Thousands of spectators gathered at the Festival of Dionysia, where the theatre held between 14,000 and 17,000 people, two and a half times the size of the assembly at Pnyx.18 Michael Lloyd describes these plays as agones and argues that contemporary Athenian life provided the formal context for the conflict of arguments in Euripides’s agones. This life took place in law courts, and in political and diplomatic debates. Sophists and rhetoricians concerned themselves with the theory and practice of argument. Citizens went to the theatre to reflect on conflicts and develop sophisticated arguments for the assembly.19

The agora was both a political and a religious centre, a place of complex associations, a place f...