eBook - ePub

The Geography of Border Landscapes

Dennis Rumley,Julian V. Minghi

This is a test

- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Geography of Border Landscapes

Dennis Rumley,Julian V. Minghi

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume is about border landscapes, with emphasis on the varying impact that political decision-making and ideological differences can have on the environment at border locations, for example. This volume by political-geography experts from across the globe provides important insights specficially into border landscapes and so serves to further our understanding of aspects of cultural landscapes.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Geography of Border Landscapes an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Geography of Border Landscapes by Dennis Rumley,Julian V. Minghi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1 From conflict to harmony in border landscapes

‘Good fences only make good neighbors

When they are not made out of sabres.’

Kenneth Boulding, 1989

INTRODUCTION

Political geographers share a compelling interest in borders and borderlands that is, in one way, the reverse of the regional model. We focus on the edges, not the cores of regions. We can observe landscapes at local scales but also must be aware of their international significance. Our methodology must incorporate the ability to study comparatively two or more borders, yet at the same time to analyse a borderland in its temporal setting. We need to consider boundaries in the traditional political-geographical mode, as lines marking the edge of national space and also as interfaces separating national units. The additional dimension that follows from the above viewpoint is essential for understanding the concept of a ‘borderland’ – the boundary creates its own distinctive region, making an element of division also the vehicle for regional definition. This paradox is at the core of the borderland concept. Boundary dwelling characteristics, unique to either side of the line, become dominant moulders of the cultural landscape within the shadow thrown by the boundary, and yet these characteristics disappear as one moves away from the borderland in either direction into the territorial domain of the states divided. Geographers have found some distinct advantages in applying this concept of borderland. It provides a basis for a legitimate and useful regional focus that could otherwise be over-looked – a small, local-scale dimension within an international context – and at the same time, the concept creates a type of miniature but very readable barometer of the changes in the relations between the states divided when studied in a temporal setting. Hence, the analysis of the cultural landscape of the border becomes the dominant focus of study.

I find John House’s (1981) operational model for frontier studies most helpful in defining the basic thesis of the present chapter – the study of border landscapes can fruitfully benefit by shifting the analytical focus from conflict to harmony (Figure 1.1). House aggregates borderland transaction flows which are integrated progressively in terms of space and time. The locally generated Az–Bz ‘borderland’ transactions are virtually non-existent along a boundary under the stress of confrontation and the threat of conflict. With the dominance of national interests and actions in whatever transboundary transactions (A–B) that take place, transactions of the Az–Bz variety are usually discouraged and often illegal. Hence, with a borderland that evolves from an extreme conflict situation, such as the chaos of open war and its consequences of instability, toward a more harmonious status, one would expect to see a marked change in the nature of A–B transactions and a sharp rise, indeed often a dominance, of the local Az–Bz transactions. The present chapter will focus on the conflict-versus-cooperation aspects in the time dimension and in the spatial context, with special emphasis on the changing nature of A–B transactions and the rise in importance of Az–Bz transactions in the shift from conflict to harmony.

Figure 1.1 Borderland transaction flow model

Source: after House (1981)

BORDERLAND STUDIES

The analysis of border landscapes in political geography has generally been directly related to the study of boundaries. The vast majority of these studies has traditionally carried an emphasis on stress and conflict, viewing the boundary as an interface between two or more discrete national territories and subject to problems directly reflecting the relations between the nation-states it divides. Consequently, the ebb and flow of boundary studies have tended to be associated with periods of territorial conflict and hostility.

In a review of boundary studies a generation ago (Minghi, 1963), it was clear that most of the boundary literature had been written during the two World Wars or in their aftermath. Many sought the causes of friction between nations and the means of avoiding it. In particular, the redrawing of boundaries based on a variety of considerations in the post-War periods attracted much research interest, whereas boundaries as political-geographic phenomena had attracted little interest in normal times. Hence most studies fell into categories such as shift in location, delimitation and demarcation, and disputed areas. Recently, Prescott (1987) confirms this finding but also points out that a boundary is a line of physical contact between states and hence affords opportunities for both discord and cooperation. Indeed, while discussing border landscapes, he talks about the ‘temptation for scholars to concentrate on the dramatic’ at the expense of the routine, with the dramatic tending to be conflict and the routine more normal, peaceful situations (Prescott, 1987: 160).

We find, therefore, a heavy concentration of conflict-related studies written at a time in which the collapse of regimes, states and entire empires, the creation of new states, and shifts in the location of national frontiers by occupation, conquest or treaty, all provide grist for the study mill of boundary problems and of the human geography of the borderlands to which these problems are linked. This political geography sub-field of research endeavour has consequently taken on a cyclical nature, with periods of intense, almost feverish research activity often funded by national interests, alternating with times of little or no attention when more normal, peaceful conditions prevail between fixed neighbours.

FROM CONFLICT TO HARMONY

I would like to argue for a new focus on boundary studies which will encourage research on the more ‘normal’ situation in boundary landscapes. This in turn will place boundary studies more in tune with recent trends in political geography which has seen a rise in the concern for making a more positive contribution to the study of peace. Specifically, I would like to see a shift from the context of war to the prospects for peace in the analysis of border landscapes, and indeed, I claim that such a shift is already under way. I make this claim based on the results of three decades of research in a variety of borderlands. I would further make the case that not only should boundary studies focus more on normal and harmonious contexts, but that such a focus on the changing nature of the human geography of borderlands tends to yield findings that can shed light on the subtle workings of the political process at all levels between and within states. Our increased understanding of such workings in the context of a borderland may well have a direct impact on our ability to understand political geographical processes within one state or the other, and should be applicable to an understanding of the geography of borderlands in other regions. This aspect of applied geography is particularly important as a potential contribution to understanding the processes of conflict resolution and peace.

Two regional examples – one actual and the other potential – will be used to make these points. The first is the Alpes Maritimes borderland of France and Italy viewed over three decades. The other, which is discussed more briefly, is the Israel–Jordan borderland in the Rift Valley between the Dead Sea and the Red Sea.

THE ALPES MARITIMES

My close observation of this borderland for over thirty years, starting in 1956 as an undergraduate field research assistant to John House, leads me to conclude that this shift from the context of war to the prospects for peace – from conflict to harmony – is very clearly reflected in the evolution of the border landscape. In the context of the aftermath of the Second World War in which France and Italy had been bitter enemies, and, in particular, following a major shift involving 410 square kilometres in the location of the boundary in favour of France in 1947, the most meaningful research questions about the borderland in the mid-1950s concerned the impact of the boundary change, so thoroughly asked and answered by House in his frequently reproduced study of this classic borderland (House, 1959).

A decade after the 1947 peace treaty, borderland life was dominated by six major sets of factors.

1 Severe out-migration, especially of the Italian population. Within six months of the peace treaty, residents of the exchanged area were to become automatically French citizens. During the previous decade, a large number of Italians had migrated into the area for jobs in the expanding public sector, such as the state railways or in construction and provision of military facilities. Following Italy’s defeat and the territorial gains by France, there was little incentive to retain this mainly urban element of the population.

2 The separation of constituent parts of the ecological whole of alpine communities adjoining the new boundary, with high pastures separated from arable land on alluvial fans in the valleys and village settlements separated from communal forest land. Indeed, the actual village site of Olivetta-San Michele was left in Italy but many of its high summer pastures and virtually all of its forest land were now in France. Possible compromises were discussed to minimise this type of disruption of the cultural landscape and, at one point, a Swiss arbitrator was appointed. The bitterness of the War and the resultant territorial growth of France in the borderland allowed for no compromise at the national level and these severe local problems were allowed to fester.

3 The flooding of entire valleys by a France with far greater needs than Italy for hydroelectric power in the adjacent region of the booming Côte d’Azur. In the first two decades after the War, the Electricité de France (EDF), France’s national power generating and distribution agency, pushed the hydroelectric generating capacity in the alpine regions to the limit, and nowhere more than in this newly acquired high alpine region so close to the power hungry Côte d’Azur, France’s fastest growing region. In a sense, the local landscape was remade to meet broader regional needs. Headwater diversions, tunnelling, and other hydrologic engineering techniques raised the area’s electricity generating capacity several fold over the previous Italian level but only at the expense of accelerating the rate of decline of the rural economy, with the flooding of arable valley land as well as access routes to pastures. In addition, the temporary but large male and predominantly Algerian labour construction crews brought in to build the new dams tended to seriously disrupt the social life of these small alpine communities.

4 The conscription of males to fight in French colonial wars in North Africa and Indochina. One of the blessings of the War for Italy, was the loss of all colonial territories. France, on the other hand, struggled for over a decade to hold on to its many colonial holdings in South-east Asia, North Africa and elsewhere. This in turn, led to a major colonial war in Indochina and later in Algeria. The male population of military age in the French segment of the borderland found themselves conscripted to fight in these wars, a bitter irony for those in the exchanged territory who had optimistically voted in a plebescite to choose a more victorious and more prosperous French state over an Italy that had brought them fascism and war.

5 The continuing dominance of security preoccupations moulding the landscape with a heavy concentration of French alpine troops. Italy had built up a large military presence in the borderland prior to the invasion of France in 1940 and hence France took particular pains to ensure a significant military occupation of the borderland in the years after the war.

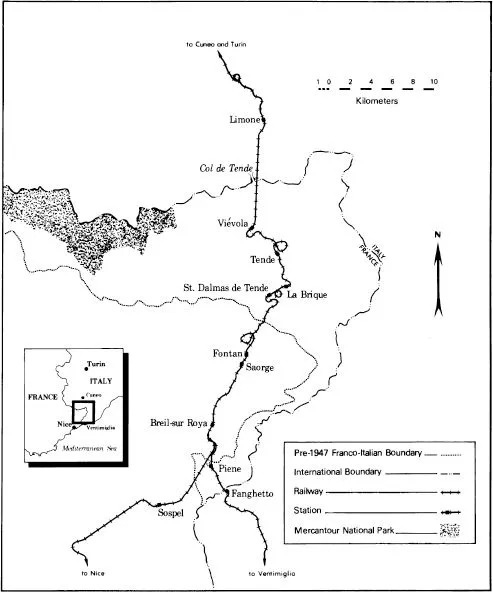

6 The continued dereliction of the Roya Valley railway, the major artery linking the region to the Po Valley and the Mediterranean Coast. Running under the Col de Tende and down the Roya Valley, this railway was completed in 1929 and destroyed during the War (Figure 1.2). The middle section of this line was now in French territory and France, although agreeing in the peace treaty to cooperate with Italy in rebuilding the railway, showed no interest in improving Italian access to the borderland or in raising the competitive status of Italy’s Mediterranean port of Ventimiglia over the nearby French port of Nice.

Given the above factors dominating in the region for well into the second decade after the War, any study of the border landscape made during this period was without doubt one of the results of conflict and hostility. Over a generation later, the same borderland offers an entirely different set of research questions. Times have changed. The bitterness and recriminations of the 1950s are gone and with it the psychology of occupation and military pressure by France to offset the previous Italian era. France and Italy are close, founder members of the European Community. The complex of social, political and economic relationships generated by this partnership have had a fundamental impact on improving the status of the borderland (Minghi, 1981, 1984). The high alpine segment of the area ceded to France in 1947 is now the Mercantour National Park directly linked by design to a tract of similar high mountain terrain across the border also declared a national park in Italy. The railway is now rebuilt and links the borderland with the North Italian Plain and the Italian city of Ventimiglia as well as to Nice in France. The central point in the line, the junction at Breil, still remained pock-marked with shells and in a derelict state into the early 1970s, thirty years after the War, whereas at its reopening in 1979, the beautifully redesigned station won the French architectural prize of the year. Similarly, the station at Tende, which remained derelict and served as a boys’ camp for thirty years, is now also refurbished for the reopened line. And all over the borderland one can find landscape evidence of the reconstructed line. Scenes of war destruction and abandonment from a generation ago are now replaced by the evidence of peace and cooperation behind the decision to rebuild. The reopened line is advertised widely as a symbol of international cooperation with posters in major French and Italian cities showing the distinctive diesel units – red French and green Italian – side by side in the alpine setting of the borderland. The borderland region is virtually demilitarised and its century-old role as a stage for military occupation and confrontation between France and Italy is over. Forts and battlements remain as fading relics in the border landscape, reduced to the role of historical curiosities. Local inhabitants can move freely across the border and adjustments were finally made in the 1960s to overcome some of the disruptions of ecological balances between settlements and their operating space. While outmigration remains a factor in the borderland’s demography, it is more on a par with other alpine regions. Indeed, some settlements in the borderland have expanded their tourist facilities in anticipation of successful exploitation of their borderland character as highly symbolic convention sites for the many Franco-Italian agencies and interest groups spawned by the success of the European Community.

Figure 1.2 The Roya Valley railway

Has all conflict disappeared in this new peaceful borderland? Certainly not. Some is still ‘national’ in origin. The issue of electrification of the reopened railway line r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of plates

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of contributors

- Preface

- Foreword

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: The border landscape concept

- 1 From conflict to harmony in border landscapes

- 2 Geographical investigations in boundary areas of the Basle region (‘Regio’)

- 3 Boundary, values and identity: The Swiss–Italian transborder region

- 4 Some developing and current problems of the eastern border landscape of the Federal Republic of Germany: The Bavarian example

- 5 Geographic problems of frontier regions: The case of the Italo-Yugoslav border landscape

- 6 The impact of sovereignty transfer on the settlement pattern of Sakhalin Island

- 7 Society, state and peripherality: The case of the Thai–Malaysian border landscape

- 8 The Indonesia–Papua New Guinea border landscape

- 9 Coastal islands on an international boundary: Dauan and Parama in the Torres Strait

- 10 Inter- and intra-regional conflicts in Pakistan’s border landscape

- 11 The Gulf of Aqaba coastline: An evolving border landscape

- 12 The evolution and contemporary significance of the Bophuthatswana–Botswana border landscape

- 13 Where the Colorado flows into Mexico

- 14 Peacekeeping missions and landscapes

- Conclusion Border landscapes: Themes and directions

- Index

Citation styles for The Geography of Border Landscapes

APA 6 Citation

[author missing]. (2014). The Geography of Border Landscapes (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1665959/the-geography-of-border-landscapes-pdf (Original work published 2014)

Chicago Citation

[author missing]. (2014) 2014. The Geography of Border Landscapes. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1665959/the-geography-of-border-landscapes-pdf.

Harvard Citation

[author missing] (2014) The Geography of Border Landscapes. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1665959/the-geography-of-border-landscapes-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

[author missing]. The Geography of Border Landscapes. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2014. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.