eBook - ePub

Political Frontiers and Boundaries

J. R. V. Prescott

This is a test

Share book

- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Political Frontiers and Boundaries

J. R. V. Prescott

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This classic work is a comprehensive treatment of the world's political frontiers and boundaries, and includes sections on boundaries in the air as well as chapters treating the subject in a regional manner, covering the continents in terms of the evolution of boundaries.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Political Frontiers and Boundaries an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Political Frontiers and Boundaries by J. R. V. Prescott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Naturwissenschaften & Geographie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

Land boundaries

Political frontiers and boundaries separate areas subject to different political control or sovereignty. Frontiers are zones of varying widths which were common features of the political landscape centuries ago. By the beginning of the 20th century most remaining frontiers had disappeared and had been replaced by boundaries which are lines. The divisive nature of frontiers and boundaries has not prevented them from forming the focus of interdisciplinary studies by lawyers, political scientists, historians, economists, and geographers. Scholars from these fields have produced a rich literature dealing with frontiers and boundaries. Any survey of this extensive literature will reveal that the following themes have attracted the most attention.

National histories and international diplomacy

When the histories of countries are unravelled it is plain that most of them did not emerge at one time within a single set of international limits which have remained unchanged. That is certainly the case with countries in Europe, North and South America, and Asia. Although it is true that many African countries, such as Somalia and Mozambique, became independent within a set of boundaries which have not been altered, research into their colonial antecedents reveals a variety of colonial boundaries. A significant part of the history of several countries concerns the struggle for territory, and the identification of previous national boundaries on a single map provides a shorthand account of stages in the progress to the present pattern of states. Often the events which established new boundaries were sufficiently important to mark the division between important periods in the political history of countries or in the diplomatic and military history of continents.

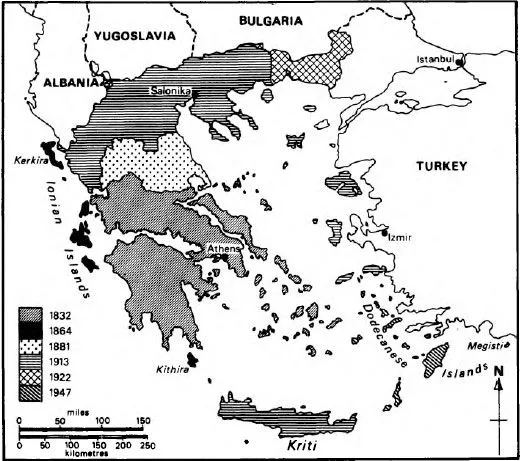

This point can be illustrated by Figure 1.1, which shows the boundaries of Greece since 1832, the year when the modern state of Greece emerged from nearly three centuries of Turkish rule. The rebellion began in the Peloponnisos in April 1821, and this area was quickly cleared of Turks. The Greek sailors also enjoyed success against the Turkish navy in the Aegean Sea, but the tide of rebellion had been halted by June 1827 and other foreign powers decided it was time to intervene to avoid continued instability in this region. The destruction of the allied Turkish and Egyptian fleets by naval squadrons from England, France, and Russia in Navarino Bay on 20 October 1827 paved the way for an enforced settlement on the terms of these countries. In 1830 it was proposed that the northern boundary of Greece should run southwestwards from the vicinity of Lamia to Mesolongion, but Palmerston then persuaded his allies that the line should run from Pagasitikos Kolpos to Amvrakikos Kolpos, as shown in Figure 1.1. However, Palmerston defeated proposals to give to Greece the islands of Samos and Kriti on the grounds that the former was too close to the Turkish coast and the latter was too valuable and had a large Turkish population which should not be subject to Greece.

Figure 1.1 The evolution of modern Greece.

On 29 March 1864, six months after Greece had installed a Danish King, Britain ceded the Ionian Islands to Greece. These islands stretch down the west coast of Ipiros and Peloponnisos from Kerkira (Corfu) in the north to Kithira in the south. These islands had been formed into the United States of the Ionian Islands in 1815 at the Treaty of Versailles and placed under the protection of Britain. Their union with Greece followed a unanimous vote of support by the Legislative Assembly in the islands.

The war between Russia and Turkey in 1877 presented Greece with an opportunity to claim the Greek provinces in Turkish Europe, but the decision to take action was delayed so long that the Greek army had no chance to march before the war was ended a month later. The peace treaty signed by Russia and Turkey at San Stefano on 3 March 1878 contained no territorial gains for Greece. Fortunately for that country the other major powers in Europe were dissatisfied with the territorial arrangements which Russia had forced on Turkey, and the treaty was revised at the Congress of Berlin attended by all the major powers in June and July 1878. Greece was not represented at this Congress, but Britain persuaded the other powers to require Turkey to make concessions to Greece along their common boundary. At first it was proposed that the new boundary should run from Stoupi in the east to the mouth of the Thiamis River in the west, opposite Kerkira. This would have given Greece the region of Thessalia and most of Ipiros. Turkey could not resist the cession of the former region with its pronounced Hellenic character, but it was able to retain the areas of Janina and Preveza, which then constituted most of modern Ipiros. The arguments in favour of Turkish control of this area centred on their large Moslem minorities. The final treaty in this period was signed on 24 May 1881, although Greece was not a party to these arrangements.

The Greek authorities overplayed their hand in 1897 when they tried to force further concessions from Turkey in Kriti and on the continent. The European powers had to intervene to prevent a Turkish victory, and Greece was forced to cede 11 small areas which had particular strategic significance along its northern boundary to Turkey. The scale of Figure 1.1 does not allow these areas to be shown.

The next major territorial advance for Greece came in 1912 and 1913 in wars first with Turkey in alliance with Bulgaria and Serbia and then with Bulgaria in alliance with Serbia. These campaigns enabled Greece to move northwards to its present boundary and eastwards along the Macedonian coast as far as the Nestos River. In the Aegean Sea, Greece gained many Turkish islands, apart from Gokceada and Bozcaada, which Turkey retained, and the Dodecanese Islands, which had been occupied by Italy in 1912. Italy seized these islands from Turkey in April and May 1912 as part of its campaign against Turkey over control of Tripoli and Cyrenaica.

The rôle of Greece in World War I was rewarded with Bulgaria’s coastlands on the northern shore of the Aegean Sea in western Thraki (Thrace) and the Turkish area of eastern Thraki as far east as Catalca within 20 miles of Istanbul. A large area of the Turkish mainland around Izmir (Smyrna) was placed under Greek control, and it was arranged that a plebiscite in five years could opt for union with Greece. The Treaty of Sevres, which conferred these gains on Greece, was never ratified, and the Treaty of Lausanne on 24 July 1924 left Greece only with western Thraki. This dramatic change had been produced by the revival of a nationalist government in Turkey, agreements between that government and the Soviet Union and France, and by Greek military defeats at the hands of Turkish forces. Turkey was also helped by the unpopularity of King Constantine with the western powers because of his pro-German policy of 1915. The Treaty of Lausanne marked a retreat from the line marking the largest territorial extent of modern Greece and Turkey’s boundary of 1914 along the Meric River was restored.

The final extension of Greece occurred in 1947 when Italy ceded the Dodecanese Islands and the island called Megisti, which Italy had obtained from France, in 1920.

In tracing the evolution of national boundaries there is no substitute for the treaties, protocols, agreements, and conventions which specify the formal arrangements between states. Sometimes these can be difficult to find, but there is now a fairly comprehensive range of publications dealing with this subject. For the period from 1648, which is ‘classically regarded as the date of the foundation of the modern system of States’ (Parry 1969, Vol. 1, p. 3), until 1919 Parry has edited a collection of treaties filling 231 volumes. From 1920 to the present many treaties are published in the League of Nations Treaty Series and its successor the United Nations Treaty Series. These collections contain only treaties lodged with these international organizations and therefore they are not comprehensive. One serious problem in interpreting treaties relates to the need to consult maps used by the negotiators and often published with the treaty. The collection by Parry does not include maps; the other two treaty series sometimes do. The importance of using maps which were contemporary at the time the treaty was signed turns on the facts that modern place names might be completely different and sometimes the maps were inaccurate and those inaccuracies were carried into the written description of the boundary. For example, the boundary between British Rhodesia and Portuguese Mozambique south of parallel 18°30′ south was defined in the following terms on 11 June 1891:

… thence it follows the upper part of the eastern slope of the Manica plateau southwards to the centre of the main channel of the Sabi … (Brownlie 1979, p. 1119)

The demarcation team sent by both countries to fix this line could not agree on the location of the upper part of the eastern slope of the Manica plateau and the matter was referred to the arbitration of Senor Vigliani, an Italian senator. He handed down his decision on 30 January 1897 (The Geographer 1971, p. 2). The original negotiators can be excused for producing such an uncertain definition in view of the maps in the archives in London and Harare. It is quite clear that the maps and accompanying cross-sections sent by officers in the field show the edge of the plateau as a prominent and apparently unmistakable feature.

Fortunately there are also regional guides to the literature and treaties dealing with the evolution of national boundaries. Nicholson (1954) and Paullin (1932) have provided detailed accounts of international boundaries in North America, and the atlas edited by Paullin contains several useful, large-scale coloured maps. Ireland (1938) has provided a comprehensive account of the stages by which boundaries in South America evolved before World War II. Brownlie (1979) has published an encyclopedia which records the boundary agreements determining the boundaries of Africa and includes clear maps of the present period. Brownlie does not provide the detailed background to boundary evolution which Ireland makes available and which is also included in the study of the evolution of boundaries in Asia by Prescott (1975). Documents connected with national claims in Antarctica are published in the collection prepared by Bush (1982) and the background to the various agreements and proclamations is found in the analysis by Prescott (1984).

There is no equivalent work for Europe or for Central America. Hertslet (1875–91) has edited a useful collection of boundary treaties for Europe, including several indispensable maps. Fortunately most of the gaps in the literature have been filled by individual studies produced by The Geographer of the State Department of the United States of America. Under the general title of International boundary study this office has now issued nearly 200 separate analyses.

Contemporary international conflict and co-operation

Boundaries represent the line of physical contact between states and afford opportunities for co-operation and discord. Lord Curzon of Kedleston, who was a Viceroy of India, summed up this situation in words that have often been quoted:

Frontiers are indeed the razor’s edge on which hang suspended the modern issues of war and peace. (Curzon 1907, p. 7)

Most commentators use these words to introduce discussion of boundary conflicts, but Curzon’s reference to peace should not be forgotten. Regrettably, newspapers and radio and television bulletins seem to regard boundary disputes as more worthy of attention than co-operation to solve boundary issues. In fact both conflict and co-operation over boundaries are important subjects for study. Indeed a survey of the volumes in the United Nations Treaty Series (United Nations 1945–) reveals dozens of treaties dealing with co-operation between states along common boundaries, as the following examples show.

On 23 October 1950 Belgium and the Netherlands defined an underground mining boundary in the vicinity of the Meuse which was independent of their boundary on the surface. This was done to reduce to a minimum the amount of exploitable coal which had to be left in the ground (United Nations 1964, Vol. 507, pp. 207–2). Austria and Yugoslavia agreed on 19 March 1953 to create frontier strips on each side of their common boundary. These strips consisted of 195 Austrian communes and 41 political communes in Yugoslavia. Citizens living within these zones were entitled to cross the boundary without the usual formalities if they owned property which straddled the boundary or if they were concerned with herding livestock or forestry on the opposite side of the line. This agreement specified 34 crossing points which could be used for this purpose (United Nations 1963, Vol. 467, pp. 380–427).

On 17 May 1963 Burma and Thailand set up a joint committee at ministerial level to confer and agree on measures to strengthen border security, to solve specific boundary problems, and to devise measures to promote economic and cultural co-operation (United Nations 1963, Vol. 468, pp. 320–9). Later, on 30 November 1963, Romania and Yugoslavia signed an agreement dealing with power generation and improved navigation on the River Danube between Sip and Gura Vaii in the vicinity of the Iron Gate. This defile in the Danube valley was made navigable in the 1890s, and the new agreement provided for the construction of two locks, two power plan...