eBook - ePub

Violence for Equality (Routledge Revivals)

Inquiries in Political Philosophy

This is a test

- 218 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Violence for Equality, first published in 1989, questions the morality of political violence and challenges the presuppositions, inconsistencies and prejudices of liberal-democratic thinking. This book should be of interest to teachers and students of philosophy and politics.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Violence for Equality (Routledge Revivals) by Ted Honderich in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politique et relations internationales & Idéologies politiques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

_______________

ON INEQUALITY AND VIOLENCE, AND DIFFERENCES WE MAKE BETWEEN THEM

_______________

Just about all political philosophy of the recommending kind is factless and presumptuous. It is of use in deciding how life ought to be, and how to get it that way, but that it is of use is only to be explained by the want of something better.

We can agree that all of philosophy, in order to come within sight of its several ends, must have far less to do with empirical fact than those disciplines which have the discovery of it and its explanation as their only end. However, in the political philosophy which implicitly or explicitly recommends action to us, or more likely inaction, premises of empirical fact necessarily have a larger importance than elsewhere in philosophy. It is not to be overlooked that recommendations of a quite specific nature are made. We are in fact urged to take a political side.

Political philosophy of this kind, to its lesser credit, is different even from moral philosophy of the traditional kind. There, one is urged towards such traditions as the Utilitarian and such commitments as to integrity. Neither the Principle of Utility by itself, nor a principle of integrity, is presumed to settle particular questions in private morality for one. It is understood that to settle questions of conduct in marriage, say, one needs something in addition to general principles, which by themselves do not tell one what to do. The additional factual premises are not and could not easily be supplied, and so, very reasonably, recommendations of a specific nature are not made. One is not told what to do in marriage.

In political philosophy of the recommending kind, one is told what to do in politics. For such recommendations to rise to being argued recommendations, they clearly need to be preceded by premises about society, empirical premises of a quite particular kind about conditions of life. Typically they are not. Nor does one have much confidence that what is said for our guidance was in fact derived, in private reflection off the page, from factual premises worth the name.

If political philosophy of the kind in question, just about all of it, is as little empirical as the rest of philosophy, and has such need to be more so that it may with justice be called factless, it is therefore presumptuous in its conclusions. However, there is also presumption in it for an entirely different reason.

The issue of political violence, to come down to that, is typically handled in a mere essay or a mere chapter, which thing does none the less end with a conclusion on the principal question. We may be told that violence, leaving aside a few chosen revolutions now dignified or indeed hallowed by time, is savage iniquity. We may be given to understand, differently, perhaps in something that falls short of plain speech, that violence of the Left must reluctantly be welcomed. It may be allowed, as certainly it should be, that what has actually been set out in support of the chosen conclusion is no more than a simulacrum of the argument for it, or, certainly better, only one part of that argument. Still, we are offered the intimation that all of the real thing, the conclusive argument itself, exists somewhere else.

This political philosophy, then, begins without essential premises of fact, proceeds by way of intimation, and delivers conclusions to us none the less. Let us make a beginning at trying to put things right.

1. LIFETIMES

In the United States, on average, blacks live for about six years less than whites.1 About twenty-nine million individuals now alive will have an average of about six years less of life than, on average, other members of their society. The average is produced, of course, by more deaths of babies, of children, of young people, and of their elders. Fewer make it through each stage of life. If there are no very fundamental economic and social changes in America, it is likely that the next ‘generation’, the blacks who are alive twenty years from now, will have an improved life-expectancy but still one that is considerably smaller than that of their white contemporaries. The rate of improvement in the past gives one of several bases for this guess about the future.2 A more precise guess is that blacks alive twenty years from now, if fundamental economic and social changes do not come about, will have an average lifetime about four or five years shorter than their white contemporaries.

The population of England and Wales has been divided into five of what are called social classes. They might also be called occupational groups, since they are in fact defined by the occupations of their members. They are labelled professional, intermediate, skilled, partly skilled and unskilled.3 The average lifetimes of males in the fifth social class were calculated some time ago to be about six years less than the average lifetime of males in the first social class. (The figure on one calculation was 5.12 years, on a second calculation 5.89 years, and on a third calculation, which seems most realistic, it was 7.17 years.4) Certainly there has been no dramatic change. There were about one and a half million individuals in question. One can guess that in twenty years’ time, if fundamental social and economic changes are not made in Britain, the unskilled class (or an analogue) will be in an improved position but still have a life-expectancy very considerably smaller than that of a professional class – more deaths at each stage of life.

Let us have before us, beside the truths and suppositions about individual lifetimes in contemporary America and Britain, two uncontentious generalizations about all western economically developed societies. We can proceed towards these by remembering that blacks in America and unskilled workers in Britain have greatly less material wealth and income than other groups in their societies.5 There are, of course, some blacks who are better off than some whites, and some unskilled workers who are better off than some members of some other occupational groups. On the whole, none the less, blacks in America and unskilled workers and their families in Britain each are large parts of a poorest group in each of the two societies. We have, then, a correlation between an economic fact and a fact about lifetimes. It is unsurprising. Indeed, the fact that the people in question come at the bottom of scales of wealth and income is the principal part of the complex cause of their shorter lives. This consideration, and many related truths about groups in the other economically developed societies, give rise to the two generalizations I have in mind about all such societies.

The first one has to do with roughly the one tenth of the present population of each economically developed society that has less wealth and income than any other tenth in that society. The generalization is that the worst-off tenth now living in each one of the developed societies will have considerably shorter lives than the individuals in the best-off tenth. It is as good as certain that they will live less long, on average, by five years or more. We must wait for precision until the time, if ever it comes, when more statistical work is done. The second generalization, as may be anticipated, is that if there are not fundamental social and economic changes in the societies in question, the situation will be better in twenty years but not greatly better.

As in the case of what was said of America and Britain, the numbers of people involved is of an obvious importance. There are now, in all of the bottom tenths of the economically developed societies, something like ninety million individuals.

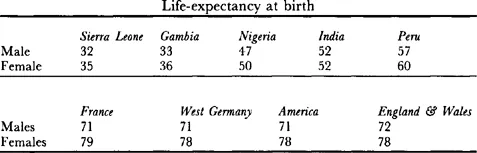

To turn to a related subject-matter, the table below6 gives a few specimen life-expectancies at birth for males and females, first for economically less-developed societies and then for developed societies. Males born in Sierra Leone have an average lifetime of thirty-two years. Males born in Britain, taking all social classes together, have an average lifetime of seventy-two years. On average, males in Sierra Leone die well before what is regarded as middle age in Britain.

The average lifetime of males and females taken together in all the less-developed societies, by one common definition of the latter, is about forty-five years. The average lifetime of males and females together in developed countries, again with the latter defined in one common way, is about seventy-four.7 About half the world’s population, then, have average lifetimes about twenty-nine years shorter than another quarter of the world’s population. It is not too much to say that what we have before us are different kinds of human lifetime.

The average figures for the two groups of societies, as the specimen figures indicate, hide still greater inequalities, those holding between particular poor and particular rich societies. There is also the greater difference in lifetimes between the top tenth of population in all the developed countries and the bottom tenth of population in the less-developed countries. There are no figures available, to my knowledge, for the latter tenth. Given evidence of various kinds, it is certain that the bottom tenth in less-developed societies have average lifetimes very much more than twenty-nine years shorter than the average lifetimes of the top tenth in developed societies. Their lives, on average, are in the neighbourhood of forty years shorter. It is not too much to say, then, that the wealthiest in the wealthy countries have two lives for each single life of the poor in the poorest countries. It is not too much to say that if one knew only the average lifetimes of these two groups of beings, one would suppose they were different species.

There is a likelihood that these inequalities in life-expectancy between developed and less-developed societies, and groups within them, will be smaller in twenty years. In the recent past, medical advances have improved life-expectancies in the less-developed societies, and it is likely that further advances will be made. None the less, unless there is a transformation in the relations between the wealthy and the poor parts of the world, there will remain an immense difference in lifetimes twenty years from now.

The numbers of people involved in these propositions about the less-developed societies are of course very great. The population of the less-developed societies, as defined, about half of the world’s population, includes about 2,500 million people. The bottom tenth then includes about 250 million people.

There arises the question of the possibility of any real change, either in the inequalities of lifetime within developed societies or in the inequalities of lifetime between developed and less-developed societies. Some will be inclined to suppose that whatever morality may say or not say, we do not have the relevant capability. Thus there is misconception in talk of large changes in lifetimes that might follow on fundamental social and economic changes. It may be objected, in effect, that it is already inevitable that the next generation of the groups in question will have a life-expectancy much like that of the present generation of the same groups.

This is mistaken, certainly or probably. Given the wealth and efficiency of the developed societies, proved in many different ways, it is clear enough that we could change very radically the life-expectancy of the groups in question. One needs to reflect, in part, on the magnitude of just such changes in the past. To consider the inequalities within developed societies, the following table gives the change in life-expectancy of American whites, at birth, over a period of forty years.8

| 1920 | 54.9 |

| 1940 | 64.2 |

| 1960 | 70.6 |

One fact of relevance, then, is that in each of two twenty-year periods in the recent past, the life-expectancy of American whites was improved to a considerably greater extent than would be required in the coming twenty years if American blacks were to come up to the level of American whites.

It is to be admitted, certainly, that the case is not clear with respect to the possibility of change in the lifetime-inequalities between developed and less-developed societies. None the less, it is beyond question that the inequalities could be dramatically reduced. The lifetime-inequalities are consequences of economic inequalities. It is my own view that no amount of economic theory can put in doubt the truth that the present economic inequalities are open to change, change which would not be damaging to present economic totals and which would dramatically reduce lifetime-inequalities.

It is worth remarking in this connection, to those who are struck by how very little has been achieved, that not much more than nothing has been attempted. In 1964 a number of the economically developed countries pledged to ‘contribute’ a percentage of their future gross national products to the less-developed countries. This ‘contribution’ was to include loans and private investment. The figure agreed upon was 1 per cent. Since that time, a number of the countries in question have failed to reach this percentage. None has exceeded it by much. The pledged total of 1 per cent of the gross national products of the developed countries in question has not been met in any year.9 This is not the kind of thing to be kept in mind in considering the question of capability. A better thing is the ‘war efforts’ of the past.

All of these generalizations about lifetimes have all of their importance in the fact that they have to do with individual human experience. It is a banal truth that typically we escape this proposition, or give it the attention of a moment. It is necessary to come closer to the reality of experience. We may do so through one woman’s recorded recollection of her daughter.

She was doing fine, real fine. I thought she was going to be fine, too. I did. There wasn’t a thing wrong with her, and suddenly she was in real trouble, bad trouble, yes sir, she was. She started coughing, like her throat was hurting, and I thought she must be catching a cold or something. I thought I’d better go get her some water, but it wasn’t easy, because there were the other kids, and it’s far away to go. So I sent my husband when he came home, and I tried to hold her, and I sang and sang, and it helped. But she got real hot, and she was sleepy all right, but I knew it wasn’t good, no sir. I’d rather hear her cry, that’s what I kept saying. My boy, he knew it too. He said, ‘Ma, she’s real quiet, isn’t she?’ Then I started praying, and I thought maybe it’ll go the way it came, real fast, and by morning there won’t be anything but Rachel feeling a little tired, that’s all. We got the water to her, and I tried to get her to take something, a little cereal, like she was doing all along. I didn’t have any more milk – maybe that’s how it started. And I had a can of tomato juice, that we had in case of real trouble, and I opened it and tried to get it down her. But she’d throw it all back at me, and I gave up, to tell the truth. I figured it was best to let her rest, and then she could fight back with all the strength she had, and as I said, maybe by the morning she’d be the winner, and then I could go get a bottle of milk from my boss man and we could really care for her real good, until she’d be back to her self again. But it got worse, I guess, and by morning she was so bad there was nothing she’d take, and hot all over, she was hot all over. And then she went, all of a sudden. There was no more breathing, and it must have been around noon by the light.10

To my mind, no breath of apology is owed to those who may say that they do not expect to find emotional matter within serious reflection. On the contrary, one must feel remiss for offering so small a reminder of human experience, or feel a despondency in the realization that so little will be tolerated.

2. VIOLENCE

The facts of violence are not so much in need of being brought forward. It is a part of what I shall discuss in this essay that we have an immediate and a sharp awareness of them. Nonetheless, should...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 On Inequality and Violence, and Differences We Make Between Them

- 2 He Principle of Equality

- 3 Our Omissions and Their Violence

- 4 On Two Pieces Of Reasoning About Our Obligation To Obey the Law

- 5 On Democratic Violence

- 6 Four Conclusions About Political Violence of the Left

- Notes

- Index