How Effective Negotiation Management Promotes Multilateral Cooperation

The power of process in climate, trade, and biosafety negotiations

- 290 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

How Effective Negotiation Management Promotes Multilateral Cooperation

The power of process in climate, trade, and biosafety negotiations

About This Book

Multilateral negotiations on worldwide challenges have grown in importance with rising global interdependence. Yet, they have recently proven slow to address these challenges successfully. This book discusses the questions which have arisen from the highly varying results of recent multilateral attempts to reach cooperation on some of the critical global challenges of our times. These include the long-awaited UN climate change summit in Copenhagen, which ended without official agreement in 2009; Cancún one year later, attaining at least moderate tangible results; the first salient trade negotiations after the creation of the WTO, which broke down in Seattle in 1999 and were only successfully launched in 2001 in Qatar as the Doha Development Agenda; and the biosafety negotiations to address the international handling of Living Modified Organisms, which first collapsed in 1999, before they reached the Cartagena Protocol in 2000. Using in-depth empirical analysis, the book examines the determinants of success or failure in efforts to form regimes and manage the process of multilateral negotiations.

The book draws on data from 62 interviews with organizers and chief climate and trade negotiators to discover what has driven delegations in their final decision on agreement, finding that with negotiation management, organisers hold a powerful tool in their hands to influence multilateral negotiations.

This comprehensive negotiation framework, its comparison across regimes and the rich and first-hand empirical material from decision-makers make this invaluable reading for students and scholars of politics, international relations, global environmental governance, climate change and international trade, as well as organizers and delegates of multilateral negotiations.

This research has been awarded the German Mediation Scholarship Prize for 2014 by the Center for Mediation in Cologne.

Frequently asked questions

Information

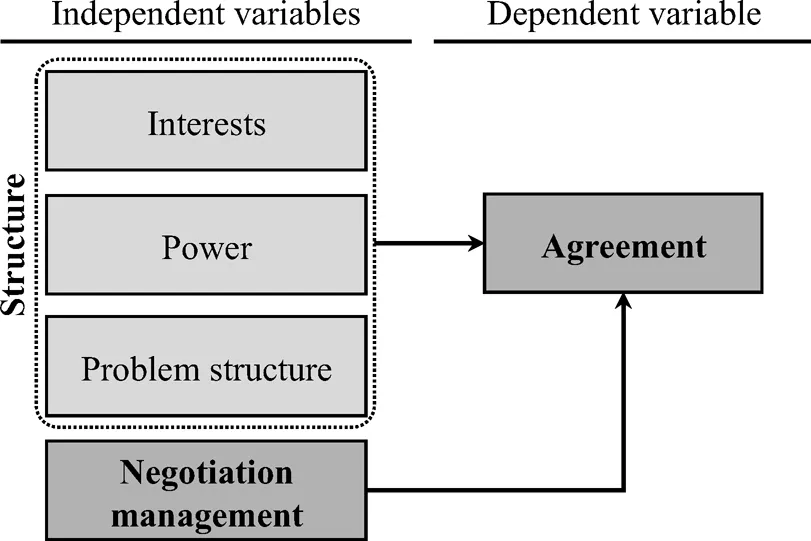

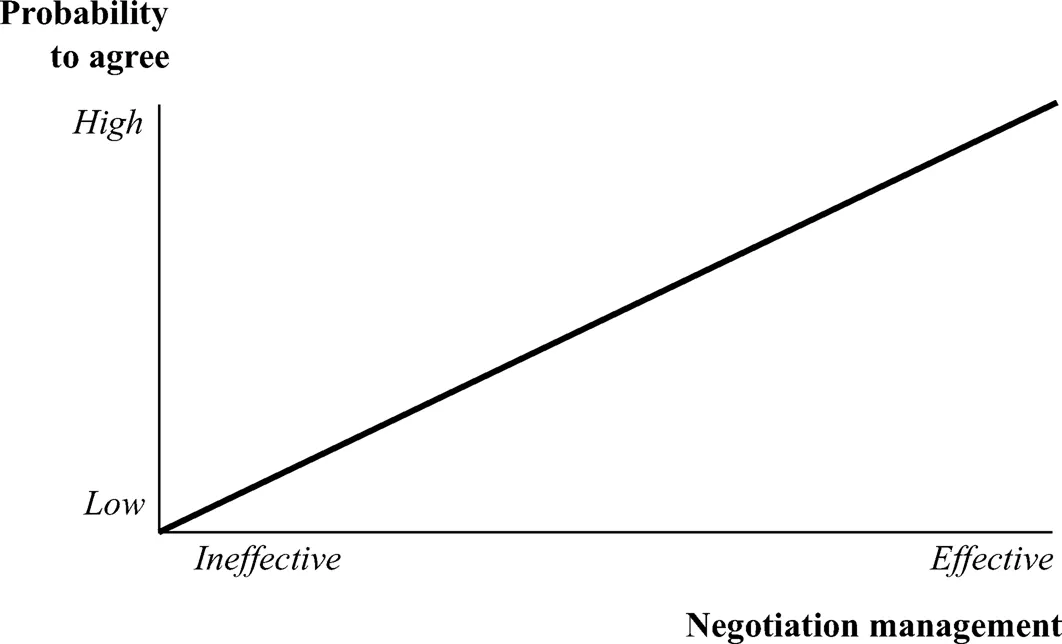

1 The argument How negotiation management alters multilateral cooperation

The argument

Negotiated agreement as potential outcome

Negotiation management as key factor

Transparency and inclusiveness

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Series Page

- Fm-Chapter1

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Fm-Chapter2

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- List of abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 The argument How negotiation management alters multilateral cooperation

- 2 The fall and rise of climate negotiations From Copenhagen to Cancún

- 3 Negotiation management during the Danish and Mexican Presidencies

- 4 Explanations of climate outcomes beyond negotiation management

- 5 Trade negotiations The bedevilled launch of the Doha Development Agenda

- 6 Biosafety negotiations The rocky path to the Cartagena Protocol

- 7 Conclusion

- Appendix I Main features of the Copenhagen Accord and Cancún Agreements

- Appendix II Questionnaire to organizers of the UNFCCC negotiations

- Appendix III Interview list on climate negotiations

- Appendix IV Questionnaire to delegates of the WTO trade negotiations

- Appendix V Interview list on trade negotiations

- Index