This is a test

- 374 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Languages of the Kimberley, Western Australia

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Kimberley, the far north-west of Australia, is one of the most linguistically diverse regions of the continent. Some fifty-five Aboriginal languages belonging to five different families are spoken within its borders. Few of these languages are currently being passed on to children, most of whom speak Kriol (a new language that arose about half a century ago from an earlier Pidgin English) or Aboriginal English (a dialect of English) as their mother tongue and usual language of communication. This book describes the Aboriginal languages spoken today and in the recent past in this region.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Languages of the Kimberley, Western Australia by William B. McGregor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Política. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Nature of Australian languages

Most Australians know next to nothing about the languages of the original inhabitants of the continent. In fact, misconceptions abound. Many believe – and this was frequently reinforced by what they were taught in school – that there is (or was) a single Aboriginal language, that this was a primitive language spoken by a primitive people, and that it had no grammar and at most a few hundred words, supplemented by gestures and grunts. It is also commonly thought that the sounds mimicked sounds of nature, and that there were no abstract terms such as love and hate, only words for specific material objects.

In fact, there were and still are hundreds of different Aboriginal languages spoken on the Australian continent. According to political criteria, there could be 500–600 languages spoken on the continent at the time of European contact – roughly one for each ‘tribal’ unit, the speech of one ‘tribe’ always being different from the speech of its neighbours (see §2.1). Sometimes the differences are very small, permitting members of one ‘tribe’ to understand members of another without previous experience of their form of speech. In these circumstances, linguists generally speak of different dialects of a single language, reserving the term language for cases where the differences are more substantial, and members of one group need to learn the other’s form of speech in order to communicate. Under this definition, something like 200–250 different languages were spoken in Australia at the time of first contact.

Australian languages are not ‘primitive’. In fact, not one of the world’s 6,000–7,000 languages can be described as ‘primitive’. Each has its own complex grammatical system and vocabulary of many thousands of words, including abstract terms. Moreover, all languages are used in certain social, cultural, and environmental context, and this is reflected in various ways in their grammar and vocabulary. It is not surprising that traditional Aboriginal languages had no terms for Western scientific and technological concepts such as ‘differentiable manifold’, ‘attractor’, ‘atom’, ‘quark’, ‘computer’, ‘television’, and so on. Nor did many languages have terms for specific numbers above about three or four. On the other hand, Aboriginal languages are better developed than English in certain areas, including kinship – instead of the handful of terms found in English they typically had scores of different words for different types of relative (see §3.2 below) – and flora and fauna, where the distinctions and classifications made in everyday speech rival those of scientific discourse in English.

As in all languages, the sounds of some words in Aboriginal languages are suggestive of their meaning. Many Kimberley languages call the peewee or mudlark diyadiya (pronounced like ‘dear-dear’) after one of its calls; likewise the word for willy-wagtail often resembles its characteristic sound – jindiwirrinyi in Gooniyandi, jindibirrbirr in Nyulnyul, and jigirrijgeng in Miriwoong. And in various languages dul (rhyming with ‘pull’) means ‘bang’, and hence ‘shoot’. But such words are the exception rather than the rule, and the sounds of words in Aboriginal languages are generally as ‘arbitrary’ and unpredictable as in any other language. Who could guess that the meaning of the Gooniyandi word thaarra is ‘dog’, or that yoowooloo means ‘man’?

It has been known for a long time that there are some striking similarities amongst the languages of Australia. Most have a word like ngayu, ngaju, or ngay for ‘I’, and many have ngali for ‘we two’. There are also widespread words including jina ‘foot’, kumbu ‘piss’, kuna ‘shit’, pina ‘ear’, and others. There are also some striking similarities in their sound systems. Most – though certainly not all! – have just three vowels, i, a, and u, and in most the first syllable of a word is stressed. Similarly their grammars share a number of features, such as the use of case-marking suffixes (similar to Latin) instead of prepositions like English to, from, and so on. Thus, to express ‘to the camp’ in Walmajarri, one says ngurrakarti where ngurra means ‘camp’, and the suffix -karti means ‘to’. Notice that the Walmajarri expression does not have a word for ‘the’; this is also a common feature of Australian languages. Another well-known characteristic of Australian languages is their extreme freedom in word order. Any order of the words in a simple sentence is usually acceptable, and all have substantially the same meaning. There are also various grammatical differences among Australian languages, and Kimberley languages differ in some important ways from languages of other parts of the continent.

Many linguists believe – though this has not been proved – that all Australian Aboriginal languages (with perhaps one or two exceptions) belong to a single family, and that they all ultimately come from a single language, usually called proto-Australian (Dixon 1980: 3). How long ago this language might have been spoken is anyone’s guess; however, it is likely to have been many thousands of years before the present. During the subsequent millennia, many differences have evolved, giving rise to the linguistically diverse situation of today. As yet this is hypothetical, and we do not know whether such a parent language existed for all modern Australian languages. Nor have any links been demonstrated with languages from other parts of the world, including the nearby island of Papua New Guinea, which was connected with the Australian continent as recently as 8,000 years ago. There are, however, some intriguing possibilities (see e.g. Foley 1986: 269–75; Nichols 1997).

1.2 The Kimberley environment

The central or core Kimberley region comprises a plateau region in the far northwest of Western Australia, extending from a rugged Indian Ocean coastline to the Fitzroy River in the south and the Ord River to the east. With an area of some 360,000 square kilometres – approximately the size of Germany and half as big again as each of Britain, New Zealand, and the state of Victoria – it is one of the least known, most inaccessible, and wildest regions in Australia, and contains some incredibly impressive scenery. What is generally referred to as the Kimberley these days is a somewhat larger region that extends south approximately 200 kilometres and east slightly less, making over 420,000 square kilometres in all. We will generally take the term in its usual sense, only when necessary distinguishing between the core Kimberley region and the wider Kimberley. Named after John Wodehouse, first Earl of Kimberley and British colonial secretary during 1870–1874 and 1880–1882, respectively, it is sparsely populated with an estimated population of just over 30,000 residents in 2000, of which slightly under a half were of Aboriginal descent.

The countryside varies considerably both in terms of geology and climate, and consequently in terms of vegetation and animal life. Geologically, the Kimberley consists of four main divisions: the Kimberley Block, the Fitzroy River Basin, the Ord River Basin, and the Great Sandy Desert.

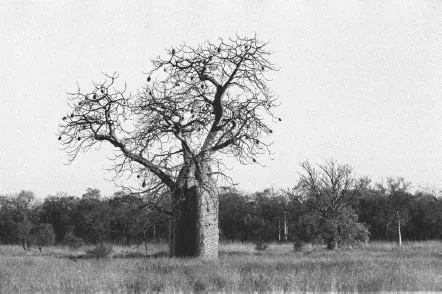

The Kimberley Block is the northernmost division, and comprises some 180,000 square kilometres. It is a plateau composed mainly of sandstone with patches of basalt, dipping in a north-westerly direction to a drowned coast. The sandstone of the plateau, formed around 1,800 million years ago in the Precambrian period, is deeply incised by rivers radiating out from the Mount House plateau area, the Charnley, Prince Regent, King Edward, Drysdale, and Durack rivers. The King Leopold Ranges bound the Kimberley Block on the southwest, and extend from Collier Bay in a south-easterly direction for around 240 kilometres. This range averages 600 metres in height, with the highest peaks, Mount Ord and Mount Broome rising just over 900 metres. The rugged Kimberley coastline is cut by drowned river valleys. Tidal variation is extreme, reaching 12 metres in places (e.g. Hanover Bay), giving rise to strong currents that made shipping hazardous in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The region is sparsely wooded; perhaps the most distinctive feature is the boab tree, a relative of the African baobab, a moisture-storing tree of wide girth.

Plate 1.1 Walcott Inlet (© Rob Jung).

The Fitzroy River Basin, dating to the Ordovician period (around 438–505 million years before the present), is a large subsidence area between the Western Australian shield in the south and the Kimberley Block to the north. In this basin flows the Fitzroy River, the largest river of the state, which traces a 525 kilometre course from its source in the Durack Range in the East Kimberley to its 10 kilometre-wide mouth at the southern end of King Sound. Despite its large catchment area, the Fitzroy River is reduced over much of its course to a series of water holes in the dry season. But during the wet season it carries an enormous volume of water that spreads out in a flood plain 100 or more kilometres wide in the lower reaches of the river.

Along the northern fringe of the Fitzroy Basin stand a series of limestone ranges running in a south-easterly direction for some 250 kilometres, from Napier Downs in the west to Bohemia Downs in the east. The ranges vary from 3 to 5 kilometres in width, and rise some 50 to 100 metres above the surrounding plains. They form a part of a massive barrier reef that formed some 360 million years ago in the Devonian period, when the area lay under a shallow sea. This reef probably then extended for more than 1,000 kilometres around the seaward margin of the Kimberley; evidence of it is also seen to the north of Kununurra, where it forms the Ningbing Range. These ranges represent some of the finest examples of fossilised reefs found anywhere in the world; marine fossils can be seen in their weathered walls.

Plate 1.2 A boab tree (© Kevin Shaw).

Plate 1.3 Countryside towards Jirrinyoowa (Cabbage Gorge) (© Tamsin Wagner).

A number of beautiful gorges have been cut into the limestone by rivers and creeks, the best known being Windjana Gorge (Lennard River), Tunnel Creek, and Geikie Gorge (Fitzroy River). The gorge at Tunnel Creek forms a natural tunnel approximately 750 metres in length through the limestone of the Napier Range. Geikie Gorge is the largest of the gorges, extending 8 kilometres through the ranges. During the wet season, the river can turn into a raging torrent, running through the gorge to heights of more than 16 metres above the dry season level. At the height of the dry season it cons...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations and conventions

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Survey of Kimberley languages

- 3 Language in Kimberley Aboriginal societies

- 4 Phonetics and phonology

- 5 Fundamental concepts of grammar

- 6 Pronouns and determiners

- 7 Nominals and noun phrases

- 8 Verbs and verbal constructions

- 9 Vocabulary and meaning

- 10 Clauses and sentences

- 11 Text and discourse

- 12 Grammar in language use

- 13 Conclusion

- Notes

- Languages and sources

- Bibliography

- Index of languages and language families

- Index of names

- Index of subjects