Photography in Educational Research

Critical reflections from diverse contexts

- 238 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Photography in Educational Research

Critical reflections from diverse contexts

About This Book

Photography in education involves the use of photographs to engage research participants in representing and reflecting upon their own experiences. This book explores how photographic images can be used in a range of educational settings in different cultural contexts, as a method of facilitating communication and reflection on significant issues in people's lives. It considers the opportunities that are created through the use of photography as a visual research method, and addresses fundamental issues about identity, representation, participation and power which underlie participatory practice.

Bringing together a variety of international contributors, chapters describe and reflect on experiences of using photography, situating them in a critical framework to provoke informed applications of these processes. The collection adopts a broad view of education, considering voices of people of different ages who are at various stages on their educational journey, or who have diverse perspectives on their educational experience: young British Muslims, trainee science teachers, audiologists, teachers of deaf children, mobile teacher educators working in conflict zones, young people with disabilities, community workers and school students, in countries as diverse as Australia, Burma, Cyprus, England, Ethiopia, Kenya, the United States and Sudan.

Photography in Educational Research will be key reading for educational researchers, postgraduate students studying research methods and ethics, tutors working in higher education, and individual practitioners and teams within schools interested in young people's voices, ethnicity, mental health, global citizenship and school development.

Frequently asked questions

Information

1 Representation and exploitation Using photography to explore education

- How can photography be used to engage with power and difference in educational research?

- How can photography be used to explore places, spaces and relationships in education/educational settings?

- How can photography be used to enquire into educational experiences?

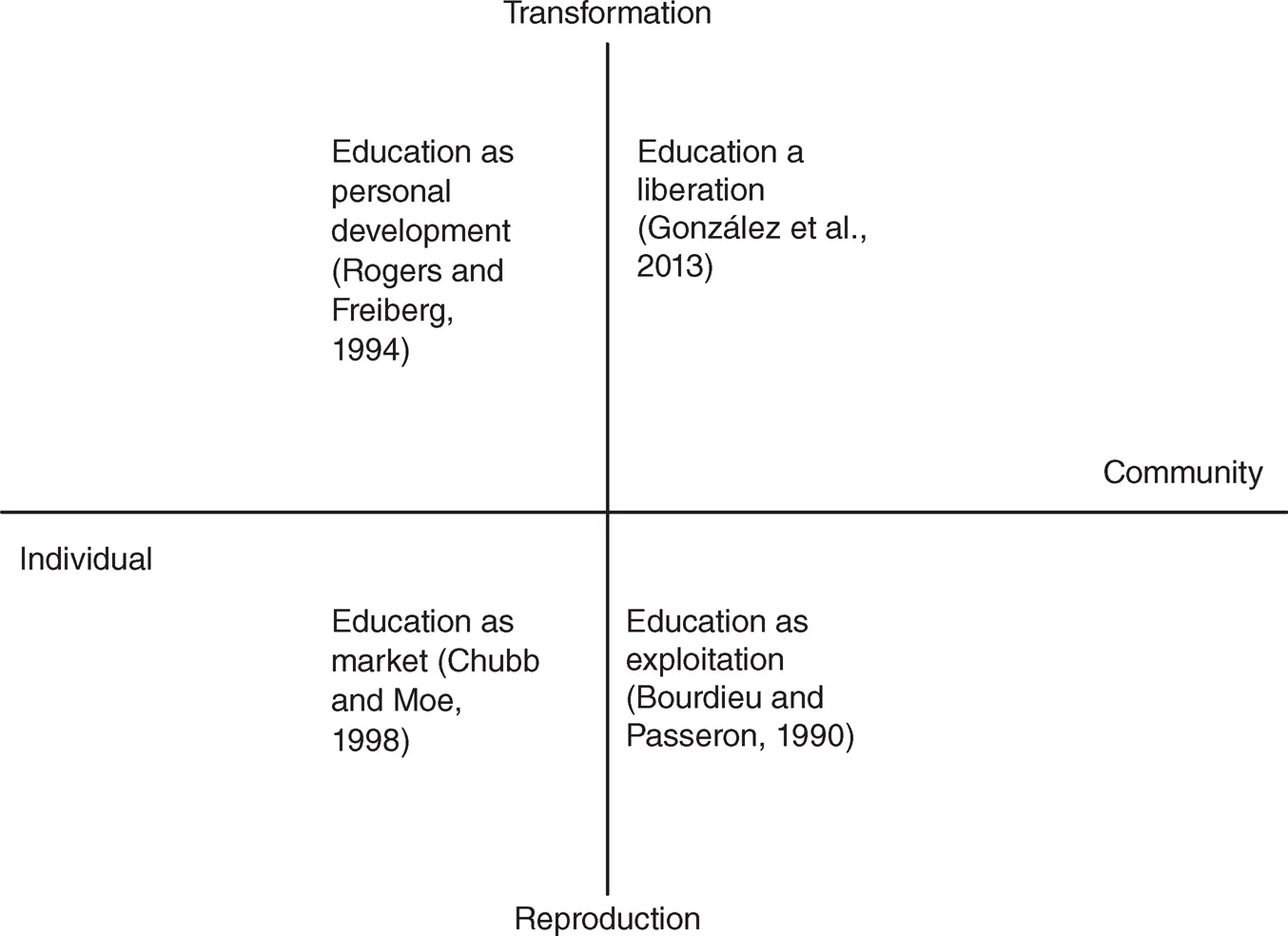

- Education as a personal project: In this view, education is about personal growth and development, through induction into the forms of knowledge that are valued and utilized in society, producing persons that are able to take part in society. It is about the formation of persons, or citizens, and in many contemporary contexts it is seen to flow from the Enlightenment: reason’s challenge to tradition and received wisdom in whatever form. Schooling is seen as a mechanism through which this induction, or training, or learning occurs, with the intention and hope that better educated persons will make a better society. Many new teachers hold this hopeful perspective. This is a widespread view, often taken for granted, and linked to the idea of education as a human right – as if education is a good, independent of context or the form it takes (Rogers and Freiberg, 1994).

- Education as a market: another dominant view addresses education as a huge industry, with schools, colleges and universities providing a service which is a commodity like any other, the possession of which enables participation in economic and social activity. This education is bought and paid for, whether by the state or by individuals, and the outcomes of education are measureable and comparable. Schools can be held accountable for their performance on these outcomes, and those with interests in the outcomes are seen as having responsibility for making decisions as consumers. In this view, parents’ decisions on the provision of education for their children, for example, is the main mechanism for driving change in the system as a whole. This is a neo-liberal view, resting on the agency of the individual or family to shape the educational market. Many people in schools work on a day-to-day basis within a reality that is heavily shaped by this view (Chubb and Moe, 1998).

- Education as exploitation: Others see education not as a route to changing society, but rather leading to the reproduction of society from generation to generation, and ask how this can be, if education entails transformation and development. They may point to the dominance of knowledge transfer as a mode of education, which places the person to be educated metaphorically at the feet of the teacher, the one who knows and whose knowledge is to be shared. They notice that this is a relationship of power, so that schools represent an exercise of power. They notice that those who are most favoured in society are in the best position to benefit from schooling, and see schooling as a sorting mechanism, passing a few and failing many, but essentially highly conservative in the effect it has in society. Exclusion and marginalization are intrinsic to the educational process, but that fact is deliberately obscured from view (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1990).

- Education as liberation: There is another view of education, which foregrounds community and society, rather than the individual. In this view, education is about expanding awareness and understanding in community, and it contains the possibilities of transformation of community. Education is not about sorting or allocation of persons to appropriate trajectories, in this view, but about the possibilities of growth at the level of communities; it involves the growth of critical engagement with existing realities, by people acting collaboratively. Education is concerned with acknowledgement of the knowledge and practice which exists in community, and with connecting that practice into broader networks of social action and change (González et al., 2013).

Ethics, power and image-based research

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of contributors

- 1 Representation and exploitation: Using photography to explore education—ANDY HOWES AND SUSIE MILES

- PART I Seeing the invisible

- PART II Reflecting on pedagogy

- PART III Articulating experience and challenging assumptions

- Index