![]()

1

CHAPTER

Introduction

Two quintessential features of humans as a species are our strong cognitive and social proclivities. Relative to other organisms, we seem to think a lot, and do so in concert with others of our kind. That is why social cognition, a discipline devoted to the crossroads of thought and social interaction processes, may afford invaluable insights into core properties of human nature.

Departing from that premise, the present volume forays into a wide range of psychological phenomena and explores them from a social-cognitive perspective. At the heart of this investigation lies the phenomenon of closed and open mindedness, of key importance to the ways in which our thoughts, often inchoate and unwieldy, congeal to form clear-cut subjective knowledge. As we shall see, an understanding of closed and open mindedness is useful not only to furthering our comprehension of how we reason and go about forming our judgments, attitudes, and opinions, but also to how we relate to and interact with fellow human beings, how we function in groups, and how we relate to groups other than our own.

As highly sentient creatures, we hardly budge without at least a degree of forethought, aimed at equipping us with a reliable knowledge base from which to launch intelligible conduct. However, objectively speaking, the cognitive activity underlying such a process has no natural or unique point of termination. It could be carried on indefinitely as we seek ever more information relevant to a given judgment or opinion. Yet our time is finite, and hence the search must be terminated at some point. On the other hand, truncating our deliberations arbitrarily, conscious of having left out considerable relevant information, wouldn't do very well either: Our judgments then might be highly uncertain and hence furnish a shaky base for actions and decisions. Yet act and decide we must, so what are we to do? It seems that Mother Nature (probably via the evolutionary process) came to our rescue with a simple solution: the capacity to occasionally shut our minds, that is, develop the sense of secure knowledge that obviates our felt need for further agonizing deliberation. Is the solution adequate? Does it always work? Does it invariably yield the intended results? The answer is a threefold no (whoever claimed that Mother Nature was a paragon of perfection?), yet our capacity for closed mindedness allows us to get on with our lives, rather than remain in an indefinite cognitive limbo, perennially buried in thought, as it were. Besides, our mental shutdown is hardly irrevocable. When its potentially adverse consequences become salient, we often seem capable of reopening the internal debate and appropriately adjusting our opinions.

Our closed mindedness potential has a plethora of significant social implications. For one, it implies that in thinking about others we may often stick to prior impressions or preconceived notions rather than flexibly altering our opinions whenever relevant new information turns up. This suggests an ingrained capacity for prejudice and stereotyping in our social judgments. Similarly, it implies the potential to jump to conclusions about others, and to form impressions based on limited and incomplete evidence.

Such closed mindedness effects are hardly limited to thinking about others; indeed, they encompass veritably all topics of human judgment, i.e., judgment and opinion-formation on various nonsocial issues as well (from nuclear physics to supply-side economics, foreign affairs, or marine biology, the safety of crossing the street, or the likelihood of reaching a corner ball in a tennis match). Moreover, they shape our relations with others in their role as informants or sources of information, as well as the targets of our judgments. Such informational sources are typically social, including live communicators, books, newspapers, or the media of electronic communication. The tendency to close our mind may then amount to creating a social closure, or a shared “reality” often via truncating social interactions and breaking off contacts with other people or groups, that is, by counting them out and proclaiming them as infor-mationally irrelevant.

Alienating though such practices might appear, there seems no ready alternative way out of our epistemic cunundrum as serious consideration of everyone's opinion is clearly unfeasible. Thus, though we cannot infor-mationally manage without inputs from some of the people, we also cannot manage with inputs from all of the people. We need to be selective about who we listen to and delineate the boundaries of our informational com-munity. This provides a powerful (albeit not an exclusive) motivation for creating social groups, giving rise to the complex and often highly emotionally charged acts of inclusion and exclusion that setting such social fences typically entails.

In short, closed and open mindedness phenomena shed light on intricate linkages between fundamental aspects of our cognitive functioning and our social nature. My purpose in this book is to explore these linkages and investigate the fascinating cognitive/social interface they illuminate. My particular perspective on these issues is motivational. Specifically, this book centers on the desire for closed or open minded-ness, how it may arise, and what cognitive and social consequences it may have. I start by outlining a theory in which the desire for closed and/or open mindedness is characterized in detail. This is followed by description of a systematic research program guided by the theory's predictions on individual, interpersonal, group, and intergroup levels of analysis. A final discussion recapitulates the major findings and high-lights their implications for various human affairs.

Though in some sense closed mindedness is inevitable, this book focuses primarily on its negative consequences for a couple of reasons: One is that such negative consequences touch on some truly important failures of human judgment and social interaction. As we shall see, closed mindedness is relevant to problems of prejudice, communication, empathy, negotiation, or outgroup derrogation, among others. Understanding its role in contributing to these difficulties may constitute an important step toward approaching them constructively. Second, it is failures of various natural processes that often provide particularly poignant illustrations of their workings (Kahneman and Tversky, 1996), thus the study of negative consequences of closed mindedness could be particularly telling with regard to human epistemic processes. For the sake of balance, however, I discuss in the final chapter some of the more posi-tive implications of closed mindedness and identify contexts where the positive or the negative consequences are more likely to appear.

Summary

The phenomena of closed and open mindedness are at the heart of the interface between cognitive and social processes. Every intelligible judgment, decision, or action rests on a subjective knowledge base held with at least a minimal degree of confidence. Formation of such knowledge requires that we shut off our minds to further relevant information that we could always strive and often manage to acquire. The relation of closed mindedness processes and social cognition and behavior is twofold. First, other people or groups of people often are the targets of our judgments, impressions, or stereotypes. Second, they are often our sources of information, and their opinions, judgments, and attitudes exert an important influence on our own. Thus, closed mindedness phenomena impact on what we think of others as well as how we think, in terms of the sources of information we take into account when forming our own opinions. The present volume highlights the motivational aspect of closed and open mindedness, discusses its antecedents and its consequences, and reports a body of empirical research exploring closed mindedness phenomena in a variety of domains.

![]()

2

CHAPTER

Motivational Bases of Closed and Open Mindedness

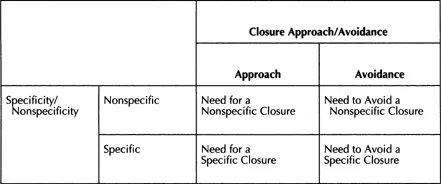

The tendency to become closed or open minded is intimately tied to one's epistemic motivations, that is, to the (implicit or explicit) goals one possesses with respect to knowledge. In a previous volume (Kruglanski, 1989) I distinguished between four types of such motivations classifiable on two orthogonal dimensions; the first, of closure seeking versus avoidance and the second, of specificity versus nonspecificity. The first distinction asks whether the individual's goal is to approach or avoid closure. The second distinction inquires whether the closure one is seeking or avoiding is of a specific kind or whether any closure or absence of closure would do. This classification yields a fourfold matrix of motivational types shown in Table 2.1: the needs for nonspecific or specific closure and the needs to avoid nonspecific or specific closure.

Two motivational continua. The four motivational types yielded by the foregoing classification can be thought of as quadrants defined by two conceptual continua. One continuum relates to the motivation toward nonspecific closure and ranges from a strong desire to possess or approach it (i.e., a strong need for nonspecific closure) to a strong desire to avoid it (i.e., a strong need to avoid nonspecific closure). The second continuum relates to the motivation toward a given or specific closure and it too ranges from a strong desire to possess it (i.e., a strong need for this specific closure), to a strong one to avoid it (i.e., a strong need to avoid this specific closure). In what follows we briefly characterize these four motivational types in turn.

TABLE 2.1. A Typology of Epistemic Motivations

Need for nonspecific closure. This particular need may be defined as the individual's desire for a firm answer to a question, any firm answer as compared to confusion and/or ambiguity. Consider a college admissions officer who desired to simply find out how well or poorly a given high school graduate did on her SAT exam in order to make the appropriate admission decision. Such motivation would represent a need for a nonspecific closure, because no particular content of an answer is preferred to any other. In other words, the need for a nonspecific closure is nondi-rectional or unbiased toward specific kinds of information. A computer user may wish to know how a particular software operates without har-boring preferences for a particular mode of operation. An air traveler might wish to know the departure gate of her plane without leaning toward a specific gate, etc.

Need to avoid nonspecific closure. As its name implies, the need to avoid nonspecific closure is directly opposite to the need for nonspecific closure. The need to avoid closure pertains to situations where definite knowledge is eschewed and judgmental noncommitment is valued and desired. Occasionally, a lack of closure may be valued as a temporary means of keeping one's options open, and of engaging in further exploration in order to ultimately reduce the likelihood of an erroneous closure. At other times, however, the avoidance of closure may be seen as a permanently desirable state. Judgmental noncommitmeht may be cherished as a means of preserving one's freedoms and a romantic sense of adventure, whereas commitment may connote the doldrums of excessive predictability and a routinization of one's life.

Need for specific closure. A need for a specific closure represents a preference for a particular answer to a question characterized by some specific property (mostly its contents) that may be flattering, reassuring, or otherwise desirable. For instance, a student's mother may strongly wish to know that her child did well on the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) so that she can hope to enroll her or him in a prestigious college. Such motivation represents a need for a specific closure because the mother desires a particular answer to her question and would not be equally happy with any answer (and in fact would be quite unhappy with some answers). Thus, by contrast to the need for nonspecific closure that is nondirectional and unbiased, the need for a specific closure represents a directionally biased influence on the epistemic process.

Need to avoid specific closure. Individuals may be motivated to avoid specific closures because of their undesirable (e.g., threatening) properties. The need to avoid a specific closure may occasionally represent the need for the opposite closure. For instance, the need to avoid a belief that one has failed an exam may be indistinguishable from one's desire to believe that one has succeeded. However, occasionally an individual may focus on the closure to be avoided without much attention to its opposite. One may wish for not losing without necessarily craving winning, or wish for not failing without necessarily dreaming of spectacular succeeding. For example, in collectivistic cultures it may be important to abide by the group norms and not fail in one's obligations to the group. On the other hand, standing out from the group by dint of markedly outperforming the other members may be frowned upon (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). In such a culture, the twin needs to avoid specific closure might develop simultaneously, that is, the need to avoid perceiving oneself as a failure, and the need to avoid perceiving oneself as a success. Tory Higgins's (e.g., 1997) work on regulatory focus draws the important distinction between prevention and promotion focus. In present terms, prevention focus might be thought of as the need to avoid the perception that one is endangered in some way, or is losing ground in some respect, hence representing the need to avoid a specific closure, whereas promotion focus might be thought of as the need to believe that one is attaining or has attained a given, desirable, state of affairs, hence representing the need for a specific closure.

Antecedents of the Motivations toward Nonspecific and Specific Closure

Approach and avoidance of nonspecific closure. The assumption that an individual's motivation toward nonspecific closure lies on a continuum and hence may run an entire gamut from a strong need for closure to a strong need to avoid closure, may seem contrary to the modern era's emphasis on the values of clarity and cognitive consistency implying a pervasive human preference for “crisp” cognitive closure over wishywashy ambiguity. This may not always have been so, however. Commenting on this very point, the sociologist Donald Levine (1985) remarked that “no one in the West before 1600 intended to cast the discussion of human affairs in the language of precise propositions. The best knowledge of human conduct, to be garnered through experience, travel, conversation, and reflection, was thought to be a kind of worldly wisdom about the varieties of character and regimes and the vicissitudes of social life” (p. 1). Furthermore, whereas the American culture is known for the premium it places on perspicuity and communicative directness, that is, on getting to the point, and saying what one means, there exist cultures that deliberately eschew excessive clarity. For example, “the Chinese language is ill-suited to making sharp distinctions and analytic abstractions; and Chinese speakers like to evoke the multiple meanings associated with concrete images. Traditional Chinese produced an ornate style that blends a complex variety of suggestive images and creates subtle nuances through historic allusions” (p. 22). Similarly, the cultivation of ambiguity characterizes the culture of traditional Java where “communication that is open and to the point comes across as rude, and … etiquette prescribes that personal transactions be carried out by means of a long series of courtesy forms and complex indirections” (p. 23). In Somali discourse “a love for ambiguity appears particularly notable in the political sphere…” (and the Somali language) permits “words to take on novel shapes that accommodate a richness of metaphors and poetic allusions” (p. 24). Laitin (1977, p. 39) has noted in this connection that “A poetic message can be deliberately misinterpreted by the receiver, without his appearing to be stupid. Therefore, the person for whom the message was intended is never put in a position where he has to answer yes or no, or where he has to make a quick decision. He is able to go into further allegory, circling around the issue in other ways, to prevent direct confronta-tion…”.

The foregoing sociological analyses confirm the assumption that human attitudes toward nonspecific cognitive closure indeed range from extreme laudation and idealization to explicit shunning and condemnation. I am assuming, furthermore, that the macro-level differentiation among cultures and historical periods in attitudes toward closure is paralleled by differences among persons and among psychological situations in the capacity to induce such attitudes. The latter emphasis lends the phenomena of closed and open mindedness a commonplace flavor and treats them as ubiquitous features of everyday life.

More precisely, I assume that the needs for nonspecific ...