![]()

1 Introduction

In 1970 Charles Eames opened the first of a series of lectures at Harvard University by describing a predicament: ‘There has developed in this country now a universal sense of expectation in which each person feels that he has the right to … anything that anyone and the other person has’.1 Later in the lecture series he addressed the increasingly materialistic attitude of the general population, asking the audience to reconsider the type of things they desire. Charles then presented the ‘New Covetables’, which were not innovative objects for conspicuous consumption, but innovative concepts, ideas, models, and skill sets.2 This departure from the rhetoric of the redeeming social value of material production was a dramatic reversal for Charles and Ray Eames, whose early reputation had been established through their design of inexpensive, high quality, mass-produced goods, evident in their 1940s mantra ‘To make the best, for the most, for the least’.3 Echoing a 1940 World War II speech in which British Prime Minister Winston Churchill said, ‘[Never] was so much owed by so many to so few’, the Eameses’ larger social ambition was established early.4 However, responding to a series of global political events in the late 1950s, the Eameses moved away from manufacturing objects and toward encouraging creativity.

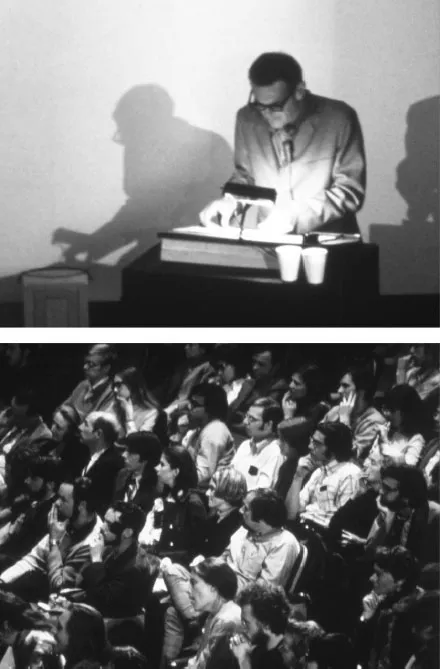

During the Harvard lectures, Charles contended that Americans had developed an improper sense of values. Starting with a crime scene, he recounted an anecdote about Ray’s car being broken into. According to Charles, the most precious item stolen was ‘a beautifully wrapped broken alarm clock that was being sent to a grandchild for further dismantling’.5 The thief being deceived by the wrapping paper proved ironic since the alarm clock had lost its functionality. However, an item not stolen was ‘a great bolt of cloth … and this was really distressing’, for ‘what was shocking about it was that the guy hadn’t thought enough of it to take it … he had not a sufficient respect for a bolt of cloth to take it’.6 The moral of the story lay in the relative values of these goods. To gain use out of the cloth required additional work, while the broken alarm clock – an item nearing the conclusion of its useful life – had educational value for the grandchild. The thief ignoring the cloth shocked Charles ‘because somehow or another a bolt of cloth comes under that sort of heading of goods … it’s fascinating because it is goods’.7 Suggesting that the audience shared the thief’s lack of appreciation for unfinished materials, Charles stated, ‘I don’t know if you remember quite, sort of, what goods are, but this is the way a bolt of cloth looks’.8 He went on to present the three-screen slideshow Goods, stating, ‘they’re goods as maybe we’ve forgotten them’.9 His contention was that the audience had lost the ability to create things themselves and only desired the finished products (Figure 1.1). Encouraging a shift away from being a society of consumers, the Eameses asked the audience to again become producers. The anecdote was not intended as an idle reminiscence, but a vision of the future.

During the opening of the lecture series, Harvard Professor Eduard Sekler introduced Charles by reciting an extensive list of accomplishments. Charles complemented this by presenting a ‘biography of situation’ during the second lecture. Within this autobiography a pattern could be discerned, as Charles linked many insignificant situations to construct a meaningful narrative of his formative experiences. Relating these to themes developed later in the lecture series, he blended science and technology with history and the arts. Charles tied his birth to the anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill, a historic event in the American Revolution. He stated that his first memory was the interruption of a piano-violin duet by his parents so they could go outside to see Halley’s Comet, and he went into detail about having read Elementary, Practical, and Experimental Physics at a young age, ‘illustrated with 680 engravings’. Charles talked about his ‘absolute passion for reading instructions’, learning to mix emulsions for wet-plate photography through a manual. When the 1929 Wall Street economic crash occurred it was not seen as a detriment, but an asset. Beginning a career in architecture during the Great Depression was ‘the greatest thing that could happen’, because the designer had to do everything: construct the church, carve the sculpture, paint the mural, and design the vestments, lighting fixtures, and rugs.10 Having left university before graduating, Charles continuously taught himself rather than depend on a formal education.

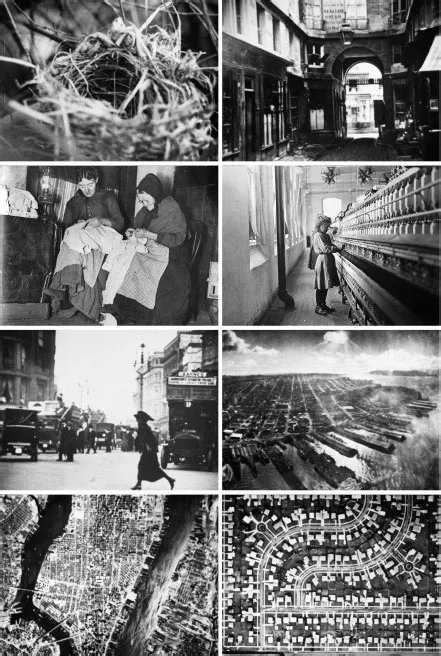

Fittingly, this autobiography never mentioned furniture. Instead Charles concluded with ‘a film about architecture’ entitled Image of the City which features photographs revealing social issues, from Jacob Riis’s portrayal of urban squalor to Lewis Hine’s images of child labour (Figure 1.2).11 A magazine mentioning Image of the City briefly describes it as ‘a film about the influence photography has had in the shaping of cities and the solving of urban problems’.12 Throughout the Harvard lectures the belief that images transform society was amplified, with the Eameses expanding the meaning of photographs by placing them within larger narratives.13 The ‘biography of situation’ ended not with products, but with the process of disseminating information to influence the trajectory of human history.

During the Eameses’ lectures they mostly omitted their furniture projects, with the office’s material production described only in abstract terms. Instead they introduced the creative process as an everyday philosophical pursuit. Their films were presented not as final products made to inform the audience, but as working examples of the need to represent scientific, historic, and philosophical ideas. Critical of the consumer indulgence generated by America’s post-war prosperity, they attempted to redefine the aspirations of the population. The objective was to lower the desire for materialistic goods relative to the desire for discourse, to make the creation of wealth less important than the creation of a body of knowledge. This position was aligned precisely with their own career trajectory, as they moved from the design of consumer furniture to the creation of educational paradigms: from personal goods to the public good.

Figure 1.1 Charles Eames delivering a Charles Eliot Norton Lecture at Harvard University, 1970.

Source: © Eames Office LLC

Figure 1.2 Charles and Ray Eames, Image of the City, 1969.

Source: © Eames Office LLC

Just after the 1957 launch of the Soviet Union satellite Sputnik 1, the United States underwent a moment of introspection. The Soviet’s achievement provoked many American designers to question established values within society, thereby expanding the purview of design.14 It was here that a tactical shift occurred in the Eames office, as the focus on designing objects that addressed pressing social and economic concerns was redirected toward creating a comprehensive educational framework that could respond to ever-changing Cold War-era demands.15 During this time the office explored multiple rationales and methods to test their vision while generating a new pedagogical model for the propagation of knowledge.

In over one hundred short films made from 1950 to 1981 the Eameses developed a social strategy that sought to increase the creative capability of each individual, contributing toward the framing of the American identity and the national trajectory.16 Unlike their educational exhibitions such as ‘Mathematica’ (1961), which presented knowledge to build curiosity around a subject, the films were examples to be emulated, revealing their process of creation in order to inspire members of the public to make their own films. The Eameses’ objective was to bring about a society in which each person would become a producer of knowledge with the ability to disseminate their ideas widely. Advocating social change, they submitted reports to museums, libraries, and institutions, hoping to grant the population access to film production facilities. Encouraging the opening of information held by corporations, governments, and universities, the Eameses sought to make knowledge more readily accessible. Similar to the unrealized 1920s proposal by Soviet film director Dziga Vertov, who believed that film production facilities and resources should be available to all citizens, in the 1950s the Eameses envisioned a comprehensive archival project. But to Charles and Ray the archive was not simply a depository of information; it was an active resource to contribute toward. Making a film was not to be limited to a select few filmmakers but to be used as an educational method, so that every film might contribute toward a better understanding of a given academic discipline, enriching the authors and audience. According to the Eameses, art should never be self-expressive, but must have the productive purpose of communicating ideas in a lucid manner. Citizens were to function as researchers who collated and combined evidence, generating a shared public resource in order to better understand the world around them. As the Eameses further developed their concepts, a parallel to the democratic model appeared: the best ideas would become more visible and widespread only through a public process. Countering the hierarchical system of state control found in the Soviet Union, their educational proposals sought to generate a system that would allow for a democracy of ideas.

A nuanced understanding of the ways in which the Eameses’ broader ambitions were intertwined with world politics can be seen through a close analysis of the diverse collection of unpublished material located in the United States National Archives, the Library of Congress, the Vitra Design Museum, the IBM Corporate Archives, the Cranbrook Archives, and the Eames office archives in California. The archival notes reveal the Eameses’ candid assessment of the problems and approach towards providing a solution, complementing the descriptions in the 1989 book Eames Design by Ray Eames with John and Marilyn Neuhart.17 Published after the office closed, Ray described Eames Design as a ‘book without adjectives’ written to give an objective account of their work.18 Conversely, Charles and Ray Eames’s archival notes contain motives, implications, and references – in other words, their notes are full of adjectives. By comparing the body of work presented in Eames Design to the body of thinking contained in the Eameses’ notes, their larger objectives may be evaluated. As I will demonstrate, they envisaged the creation of a film archive as an ongoing collective endeavour through which knowledge may be accumulated and distributed so as to encourage changes in society while exemplifying the principles of democracy.

Notes

1 Charles Eames. ‘Norton Lecture One.’ Harvard Norton Lecture Series. Cambridge, MA: Eames Office Archives, October 26, 1970.

2 The 1970–1971 Harvard Norton series of six lectures occurred late in their career, providing a retrospective of the motives behind their work by connecting the projects together in a philosophical manner. The ‘New Covetables’ was presented during Harvard Norton Lecture Five on March 29, 1971.

3 Many variations of their mantra exist. ‘We want to get the most of the best to the most for the least’ appears in Paul Schrader. ‘Poetry of Ideas: The Films of Charles Eames.’ Film Quarterly, Spring 1970: 2–19, 6.

4 Churchill stated ‘Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few’ during the Battle of Britain, the air battle between the Royal Air Force and the German Air Force. The Battle of Britain was viewed as a turning point in the war, as Britain expected a ground invasion if the German Air Force gained air superiority over the UK. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, House of Commons, August 20, 1940.

5 Charles Eames. ‘Norton Lecture Four.’ Harvard Norton Lecture Series. Cambridge, MA: Eames Office Archives, March 15, 1971.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

...