- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Regional Trade Arrangements

About this book

NONE

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

1992eBook ISBN

9781557752277V Experience with Regional Integration: Developing Countries

Regional integration schemes have featured highly in the policy agenda of developing country governments during the past three decades, although the strength of the commitment to such arrangements has fluctuated considerably. Developing countries have typically considered regional integration efforts to be, at a minimum, conducive to economic development and political stability in the region as well as to the bargaining position of developing countries in multilateral forums. At times and in some cases, regional integration has been considered essential for self-sustaining growth and development. Views on the role that regional integration might play in development have evolved in line with changing historical circumstances and economic and political philosophies.

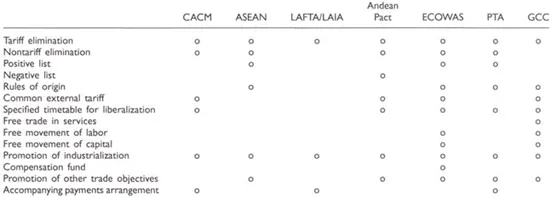

The great variety of regional integration arrangements among developing countries defies easy generalization. Box 2 provides general information and Table 7 more detail on the specific objectives of existing regional groupings, particularly those emphasizing preferential (reciprocal) trading arrangements, in the form of free trade areas or customs unions. (See also Appendix for the membership of these groups.)

Table 7. Selected Regional Trade Arrangements in Developing Countries: Main Objectives

A movement toward regional integration schemes in Latin America began in the 1950s, leading to the establishment of the Latin American Free Trade Association (LAFTA) and the Central American Common Market (CACM), both in 1960. Although stimulated in part by regional arrangements formed in Europe during the 1950s, the Latin American cases were based on an entirely different rationale. Reflecting the predominant economic philosophy of the times—promoted largely by the Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLA)—intraregional trade liberalization was seen mainly as a means to overcome the limits imposed by small domestic markets on an import-substitution development strategy. The expectation was that larger regional markets would engender economies of scale and provide firms with a “training ground” to gain the competitiveness needed for later success in world markets (Morawetz, 1974). This view permeated the design and choice of integration instruments in Latin American arrangements, most notably the CACM and the Andean Pact but also the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), where explicit means were devised to allocate import-substituting industries among members while attempting to ensure “balanced” industrial development. Interest in regional integration declined somewhat from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, against a background of disappointing results in the major Latin American group (the LAFTA) and the emergence of the debt crises in the 1980s. Under the current revival of regionalism on the continent (see Chapter III), the previous emphasis on import substitution appears to be giving way to a more outward-oriented and market-based approach, both in new regional arrangements and in old arrangements being revived.

The historical roots of regional integration schemes in sub-Saharan Africa may be traced to decolonization. Regional integration has been seen as a key means for cooperation in the midst of the often centrifugal forces stemming from the complex process of nation building. Against the background of fragile economic units, all regional integration arrangements in sub-Saharan Africa have emphasized collective economic self-reliance and security, with intraregional trade liberalization considered a key mechanism for achieving shared aspirations for growth and development. Sub-Saharan Africa has the largest number of regional groupings in the world, with considerable overlapping membership. It also has the largest number of ineffective or dormant arrangements. The Lagos Plan of Action, launched by the Organization of African Unity in 1980, provided a unifying framework for these arrangements. This plan envisages separate but convergent efforts toward integration in the three sub-Saharan African subregions: West Africa, East and Southern Africa, and Central Africa. The main arrangement in the first subregion is the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)—established in 1975—which encompasses and broadens the memberships of the Economic Community of West Africa (CEAO) and the Manu River Union (MRU). The Preferential Trade Area (PTA), in operation since 1984, was established for Eastern and Southern Africa. With regard to Central Africa, the Economic Community of Central African States (CEEAC) has been under negotiation for some time; it would encompass and broaden the memberships of existing arrangements in the subregion, namely, the Customs and Economic Union of Central Africa (UDEAC) and the Economic Community of the Great Lakes Countries (CEPGL). Approaches to regional economic cooperation not emphasizing preferential trading agreements have also emerged, illustrated in particular by the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC), established in 1980. The SADCC is excluded from this analysis, since it did not aim to increase intraregional trade; however, it made significant progress in other areas (see Box 3).

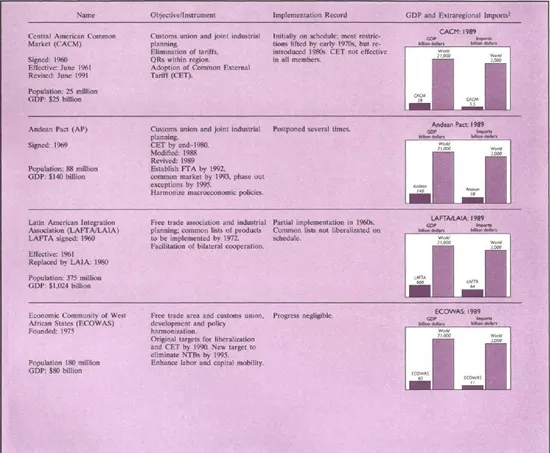

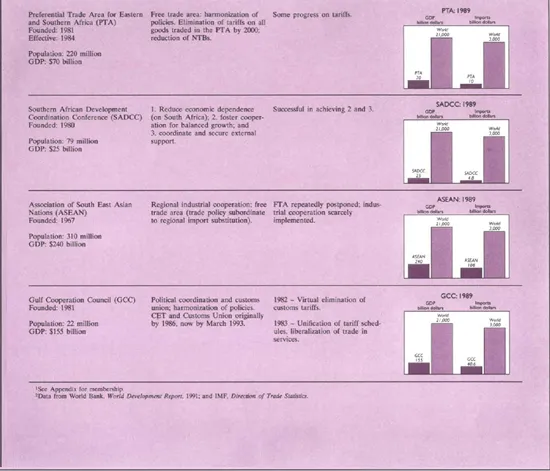

Box 2. Selected Regional Trade Arrangements in Developing Countries1

1 See Appendix for membership.

2 Data from World Bank, World Development Report, 1991; and IMF, Direction of Trade Statistics.

Broadly speaking, the enthusiasm for regional integration arrangements in Asia and the Middle East has not been to date as pronounced as in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. Sharp ideological differences, political instability, frequent military hostilities, and substantial economic heterogeneity (in terms of market size, resource endowments, and per capita income level) among countries explain why regional integration schemes involving intraregional trade liberalization have not been numerous in these areas (Langhammer and Hiemenz, 1990). The same reasons, however, seem to have favored a variety of political and economic cooperation agreements. For example, the success of the Association for South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), established in 1964, stems not from intraregional trade but mainly from it having become an effective interlocutor for cooperation in economic matters and foreign affairs with OECD countries. Ambitious plans for integration contained in the design of the Arab Common Market (ACM) and the Maghreb Customs Union, both established in the 1960s, have remained largely unimplemented. By contrast, cooperation efforts have achieved considerable success in a number of cases, including, among other things, an earlier agreement on Regional Cooperation for Development among the Islamic Republic of Iran, Pakistan, and Turkey—replaced in 1985 by the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO)—and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), established in 1981.

Intraregional Trade

The following analysis is based on regional arrangements in which intraregional trade liberalization had been expected to play a central role. (The assessment does not focus on noneconomic objectives of regional integration arrangements. Nor does it apply to agreements geared exclusively toward economic cooperation or to the economic cooperation aspects of integration arrangements.) In general, regional arrangements among developing countries have not led to a large or sustained rise in intraregional trade (Tables 8 and 9, and Chart 2), but they have been more successful in other areas of economic cooperation. Further scope may there-fore exist for enhancing such cooperation in the joint production of “software” public goods, such as education and training; research and development, particularly in agriculture; joint management and control facilities; and coordination of investment incentives.

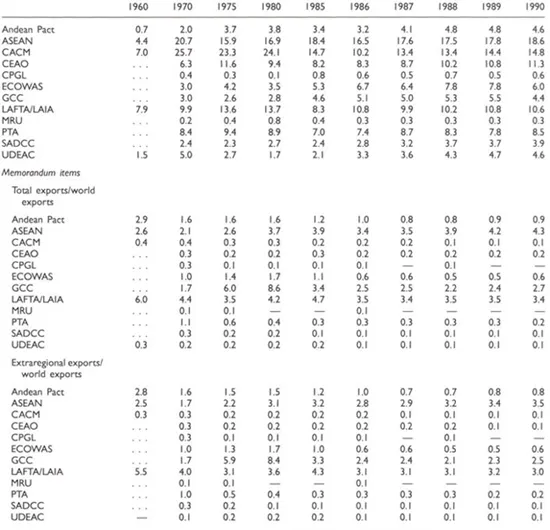

Table 8. Selected Developing Country Regional Arrangements: Intraregional Exports

(In percent of region’s total exports)

Sources: IMF, Direction of Trade; International Financial Statistics; World Economic Outlook; and IMF staff estimates.

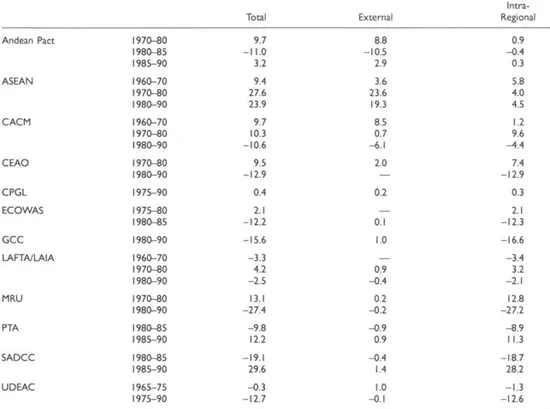

Table 9. Selected Developing Country Regional Arrangements: Changes in Trade to GDP Ratios

Sources: IMF, Direction of Trade; International Financial Statistics; World Economic Outlook; and IMF staff estimates.

Box 3. Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC)

This paper focuses on regional arrangements aimed mainly at trade liberalization. Trade liberalization is not a major goal of the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC), and its strong performance has, therefore, not been discussed. Its effectiveness as a regional organization may, however, have lessons for others, while its focus on establishing cooperation in other areas has been important in facilitating trade (Chart 2).

The SADCC, founded in 1980, comprises ten member states.1 Its main objectives are to reduce economic dependence, particularly on South Africa, foster cooperation among members on projects to promote a balanced regional development, and coordinate and secure support from “cooperating partners” (that is, foreign donors).2 The SADCC’s pragmatic approach emphasizes flexible and feasible cooperation on specific projects rather than detailed and highly formalized multicountry agreements. The SADCC does envisage expanding trade among members, but mainly along the narrow lines of production covered by SADCC-sponsored industrial programs. Although more recently, the SADCC has shown interest in liberalizing internal trade, it continues to adhere to the motto: “let production push trade rather than trade pull production.”

Consistent with its pragmatic approach, the SADCC has a small secretariat (in Gaborone, Botswana), which performs limited coordination, conducts research on regional issues, and takes the lead in certain regional policy discussions. The main responsibility for coordinating sectoral programs is assigned to individual members (for example, food security to Zimbabwe, and energy conservation and development to Angola). SADCC policy is set annually at a summit meeting of heads of state, where priorities are established and decisions on which projects to include as official SADCC projects are made. Decisions on individual sectors are made by the relevant ministries. Eligible projects must have substantial regional content. The annual Consultative Conference, which includes open meetings with “cooperating partners” (that is, foreign donors), is equally important because it provides funding to SADCC projects.

The SADCC as a whole is relatively small in economic size. Its GDP of about $25 billion compares to that of Chile or Morocco, while its population of 79 million is comparable to that of Mexico, yielding a low per capita income (about $315). A number of SADCC countries, however, are relatively rich in such mineral resources as copper, cobalt, chrome, diamonds, gold, silver, and uranium. Nearly all members are heavily dependent on South Africa, which supplies about one third of SADCC imports. Intra-Conference trade has remained below 5 percent of total SADCC trade since the 1970s (Chart 2), and nearly half involves semi-manufactured and manufactured goods, compared to 10 percent for total SADCC trade, which suggests some potential for regional trade creation. However, about 80 percent of intra-Conference trade is accounted for by Zimbabwe, which is the most industrialized member of the SADCC, deriving about 30 percent of its GDP from manufacturing. Six of the ten member countries are landlocked. Transport and communication networks—particularly rail links to Mozambique ports—have been often and severely disrupted by guerilla attacks, causing certain landlocked members to shift to substantially longer and costlier routes to South African ports.

The SADCC has been rather successful in achieving some of its objectives, although its economic dependence on South Africa has not been appreciably reduced. The SADCC’s focus on specific projects has helped mobilize foreign donor support and the delegation of responsibilities has enhanced efficiency in project implementation. Attention has appropriately centered on projects with substantial positive externalities for the region, with transport and communications at the top of the SADCC priority list during most of the 1980s. Despite military activity around transport corridors, by 1990 60 percent of transit traffic from the six landlocked states moved through SADCC ports, compared with only 20 percent in 1980, and national power grids in six member states had been interconnected. Progress was also made in the 1980s in other priority areas, particularly food security. By the late 1980s, the SADCC could point to visible achievements: firms were increasingly shipping and receiving cargo through ports and railways improved under SADCC auspices (which was particularly beneficial for landlocked countries); air links had also improved, including cooperation between national carriers; the intra-Conference share in the SADCC total international telecommunication traffic had risen to about 15 percent (compared to 8 percent in 1980), and new crop strains from the SADCC research center were being used. In terms of value, transport and communications accounted for over 75 percent of SADCC-sponsored projects followed by food and agriculture (12 percent), and energy (8 percent). Mining, industry and trade, manpower, and tourism accounted for the remainder (Hanlon, 1989).

This has entailed a shift in favor of what the SADCC calls the “enterprise sector” (private firms and parastatals), including through greater efforts at cooperating with the private sector and improving the environment for foreign and domestic investment in regional industrial enterprises. The SADCC has also stepped up efforts to improve the investment climate and to address the problem of human resource development, especially the shortage of well trained manpower and low productivity.

1 Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia (joined in 1990), Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

2 All SADCC members are eligible for membership in the Preferential Trade Area for Eastern and Southern Africa (PTA) and eight SADCC members (Angola, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe) have joined it. Four SADCC members (Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, and Swaziland) belong with South Africa to the Southern African Customs Union (SACU).

The performance of regional integration arrangements may be assessed by comparing actual results to initial objectives. Two measures of performance are useful in this regard. The first examines whether the arrangements have succeeded in achieving their fundamental goal of raising intraregional trade. The second looks at the extent to which the arrangements have succeeded in implementing initially agreed liberalization timetables. Given that an increase in the share of intraregional trade is not, in itself, an indication of welfare gains for member countries (trade-diversion effects may predominate), an alternative approach would be to assess, ex post, the net gains associated with the arrangements, in terms of static trade-creation versus trade-diversion effects and in terms of dynamic effects on growth and development. The latter assessment is inherently difficult because it presupposes an ability to guess correctly what would have happened in the absence of the regional integration and under alternative policy scenarios.

The main exception to the general rule that the formation of these arrangements did not increase trade among members is the CACM during its first decade of existence; its share of intraregional exports rose sharply between 1960 and 1970 but stagnated in the 1970s and declined in the 1980s (Table 8). The LAFTA also experienced an appreciable increase in intraregional exports during 1960–80. In the case of the ASEAN, while the share of intraregional trade is not insignificant (18.6 percent in 1990), it declined in the 1970s and has remained fairly stable since then. Moreover, the ASEAN’s relatively high share of intraregional trade can be explained by transshipment trade. The remaining arrangements that have operated for over a decade have recorded only small increases, at best, in the share of intraregional trade, which in many cases has been subject to fluctuations and reversals.

The relative importance of intraregional trade remains low for most groupings, although the variance is significant. In 1990, the share of intraregional exports ranged from a high of 18.6 percent in the case of the ASEAN, to regional groups in Africa with shares typically below 5 percent. The shar...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- I. Introduction

- II. Economic Costs and Benefits of Regional Integration

- III. Recent Initiatives

- IV. Experience with Regional Integration: Industrial Countries

- V. Experience with Regional Integration: Developing Countries

- VI. Implications of Regional Integration for the Multilateral System

- Appendix. Membership of Selected Regional Trade Arrangements

- References

- Boxes

- Footnotes